|

|

Moonlight Mile hasn’t gotten to the Moon yet, but continues to offer a mix of interesting technology and substandard plot and characters. (credit: All images Copyright Yasuo Ohtagaki/Shogakukan Inc.) |

Nothing ever happens on the Moon

by Dwayne A. Day

Monday, June 16, 2008

Television writer Mike Cassutt once famously wrote that the most amazing thing about weekly television shows is not that they are sometimes good, but that they are even made at all. A lot of people working very long hours somehow manage to produce a one-hour television show in about a week.

But let’s get back to the crap part.

A couple months back I reviewed the first two disks (eight episodes) of the new Japanese anime series Moonlight Mile, set approximately two decades in the future and focusing on the adventures of two astronauts, one Japanese, the other American. (See: “Miles to go before the Moon,” The Space Review, April 21, 2008). The third disk, with episodes 9–12, was released in the United States in May.

Alas, like the first two disks, it’s not that good.

As I noted in the earlier review, this is a series that would actually be better—rising to the level of good, not great—if it was edited down. Eliminate about a third of the material, get rid of the crudeness, profanity, and stupidity, tighten up the story, and it would be more engaging and fun.

| This is a series that would actually be better—rising to the level of good, not great—if it was edited down. |

Episodes 9–11 essentially represent a mini story arc, focusing on Gorou (pronounced “Goro”) Saruwatari, the Japanese astronaut “builder” who has been selected by the International Space Agency because of his skill with complex heavy machinery. Gorou is slated to be one of the first astronauts to conduct large scale construction on the Moon, where a new power facility for beaming energy to Earth is planned. In episode nine, Gorou has just returned to Earth a hero, having saved Sydney, Australia from destruction by a large falling spacecraft. He is assigned to test out Japan’s new engineering pride, a two-legged robotic Moonwalker.

As the story starts, Gorou is testing a walker underwater, where it is buoyed up by cables from a ship above. The walker has been experiencing various development problems. Gorou is surrounded by safety divers. But something goes wrong and Gorou’s walker tips over, trapping and crushing one of the divers, who is mortally wounded.

Gorou then befriends one of the walker’s designers, who is crestfallen about the accident. The engineer feels guilty about what happened, but Gorou is nonchalant, expressing little remorse. Because they are concerned about a possible coverup, the two men start their own investigation of the accident. What they uncover is unexpected.

Despite their frequent ham-handedness at writing interesting characters and plots, the show’s writers demonstrate a substantial knowledge of American and other space programs. This is a space geek’s paradise, clearly intended to appeal to spaceflight aficionados. In the case of the walker accident, the writers have chosen to turn a typical spaceflight stereotype upside down. (Major spoilers ahead.)

It turns out that the walker is actually ahead of schedule and works perfectly. The accident was the result of its designer, a famous academic engineering professor, concealing the vehicle’s progress in order to prolong its development. More time spent fixing nonexistent problems translates into more money. But he goofed in his effort to hide the fact that his machine was finished, and that inadvertently led to the death of the diver. Eventually Gorou exposes the designer’s deception and all is well with the program.

This is a rather clever twist—if only it was true in real life. Wouldn’t it be great if space projects were completed ahead of schedule and under budget, forcing their designers to hide that fact? Alas, this is only the world of make believe. In the real world, everything costs more and takes longer to build.

The story arc lasts for three 22-minute episodes and it is way too long. Nothing happens. And then, for a long time, nothing continues to happen. And once again Gorou is somewhat inconsistent as a character. The big problem with him in the early episodes was that he was a hard-drinking, whoring, working-class slob. This clashed with the fact that he was also supposed to be hard-working, dedicated, and brilliant. Gorou’s rough edges were simply too sharp to accept. But in spite of all this, he was never mean or uncaring. He may be crude, but he is a nice guy at heart.

|

But in these three episodes, he comes across as cocky and callous. He seems to be almost completely unaffected by the fact that a vehicle that he was driving killed a man who was there to protect him. He seems so sure that he did nothing wrong that the fact that a man died is almost unimportant to him—although clearly he is intent upon finding the real cause of the accident. It’s a combination that does not quite work. What kind of person could do something, even completely without fault, that results in the death of another human being and not feel some twinge of guilt? A sociopath, that’s who. And certainly not the kind of person you want to give the keys to billions of dollars of space equipment.

These three episodes are also a little short on the technology and depictions of spaceflight that otherwise make Moonlight Mile watchable. As with the earlier episodes, the characters are not as well-drawn (literally and figuratively) as the technology. The men all look like they are hyped up on steroids and the women like they have floatation devices strapped to their chests. The space scenes, however, are still quite beautiful, even when they’re not at their best.

|

Episode twelve focuses on Gorou’s American friend, Jack “Lostman” Woodbridge. Like Gorou, Lostman is a celebrity after the heroic spacecraft rescue. He is being followed around by paparazzi intent on photographing everything he does. Two particularly zealous photographers spot him talking to a senior American government official and suspect that he is doing something clandestine. They track him and determine that he is involved in some kind of secret project based out of Area 51 in Nevada and headed by a legendary and ancient engineer who has run many previous secret spacecraft projects.

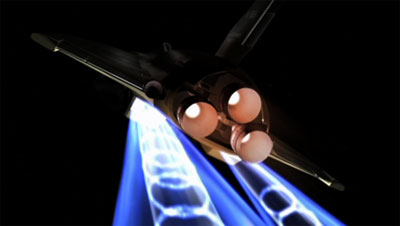

One of the series’ subplots is that while the international civilian space program is big and complex, there is also a highly secret American military space program that may be even bigger and more complex. The military has its own, ridiculously large, stealthy space station. It also has space fighter craft. Exactly why the military needs all these assets in space is not yet clear after 12 episodes, although there is a brief hint in this latest episode that the military is actively monitoring a secret Chinese space capability from a sophisticated command center.

|

As the photographers get closer to uncovering the existence of the secret space program, the spooks try to scare them off, but that doesn’t work. Finally, Woodbridge speaks to one of them and politely tells him to back off, because he’s poking into national security issues that could get him killed. The photographer is undeterred and Woodbridge washes his hands of the situation, figuring that since the men have been warned, they deserve what they get.

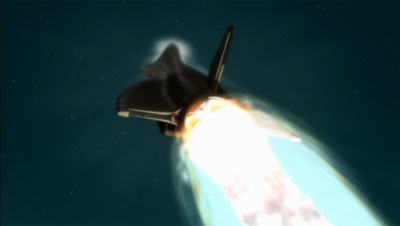

The episode culminates with a dramatic sequence involving the launch of a new top secret spaceplane known as the X-68 Nightmare, which uses both rocket engines and scramjets to boost it into space. It emerges from its desert hangar, screams down the runway, and heads off toward space. The entire time it is being filmed by the two photographers with sophisticated equipment. But the military shows up and kills them.

While the photographers are meeting their doom on the ground, Woodbridge is flying the Nightmare into orbit, headed toward the military’s massive top secret space station. It’s probably one of the best sequences of the series so far.

The Nightmare subplot was clearly inspired by the story in Aviation Week a few years ago speculating about a top secret American spaceplane called Blackstar. That storyline was also emulated by “The West Wing” and a special episode of The History Channel’s “Dogfights” series as well, indicating that it has now entered the cultural lexicon, even though the original story was very badly sourced and has not aged well (two years later and no further evidence). This is fiction. Then again, so is Blackstar.

| Is it a small miracle that even substandard anime like Moonlight Mile gets made at all? Actually, it probably is a small miracle that reasonably realistic spaceflight fiction gets made for any visual medium. |

Twelve episodes into Moonlight Mile and we still haven’t gotten to the Moon. The characters are still putzing around in low Earth orbit, doing various things that don’t quite make sense (a lot like the real space program). Just what, exactly, the US military is doing with its big space station remains unclear. The most likely possibility is that the American government is concerned that the new facilities being planned for the Moon’s surface could be attacked or seized by the Chinese, but so far none of that has been revealed in the first twelve episodes—which brings up another problem with the series: the maddeningly slow pace at which it is being released in the United States. Anime fans inform me that this is actually rather typical for many anime series. Apparently anime American distribution schedules are determined by a caffeinated marmoset throwing darts at a calendar inside some studio in downtown Tokyo. Unless you have Netflix, or a serious space anime addiction, you should not buy these DVDs. Instead, you should wait until a year or two from now when ADV Films inevitably (one hopes) bundles them all together and releases them as a package set, hopefully with some extras (although what they really need is not extras, but a severe edit). The disks are way too expensive to buy individually anyway—the first three disks would cost over $80 even at Amazon’s discounted price.

But all of this brings me back to Mike Cassutt’s statement about live action television. I honestly don’t know enough about animation, particularly Japanese anime, to determine if the same observation applies as well—is it a small miracle that even substandard anime like Moonlight Mile gets made at all? Actually, now that I think about it, it probably is a small miracle that reasonably realistic spaceflight fiction gets made for any visual medium. The Japanese fetishize technology more than just about anybody else, and what shows like Moonlight Mile, and the much better Planetes and Freedom (also still not fully released) demonstrate is that Japan has a core group of geeks who are fascinated about—and practically worship—American space technology. They understand the technology and the politics quite well, even if they cannot write reasonably realistic characters or dialogue.

As much as I feel embarrassed to admit it, I’m awaiting the next disk in the Moonlight Mile series, sure that I’ll gripe about its failings as well. That is probably more amazing than the fact that such mediocre stories get filmed at all.

Dwayne Day has written about a number of near future space anime series. He still needs to buy the soundtrack to Cowboy Bebop. He can be reached at zirconic1@cox.net.

|

|