Blue collar artby Dwayne A. Day

|

(credit: NASA) |

“I was born and raised in Cleveland,” Bossinas explained of his background. He still lives there. It’s cold in the winter. “That’s what I hate about it!” he joked. He liked to draw from a young age. “As a kid I didn’t draw hardware a lot. I’d draw zooming cars or things like that, rather than horses,” he laughed, saying that it was probably why his career ultimately went in the direction that it did.

(credit: NASA) |

After serving in the Korean War, he used the GI Bill to obtain a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Ohio University. After obtaining his degree he held several different artist and graphic design jobs. For awhile he worked for American Greetings Corporation, the greeting card company headquartered in Cleveland. Much of Bossinas’ work there did not involve illustrating greeting cards, however, but rather all the other paper products that the company produced, such as party decorations.

(credit: NASA) |

After American Greetings, Bossinas went to work for White Motor Company, an American automobile and truck manufacturer that existed from 1900 to 1981 when, like so much of the American automobile industry in the Rust Belt, the company became insolvent, and was bought and split up. Although he liked working there, he admits that it was rather limiting. “There’s not a whole lot of styling in a highway tractor,” he explained.

(credit: NASA) |

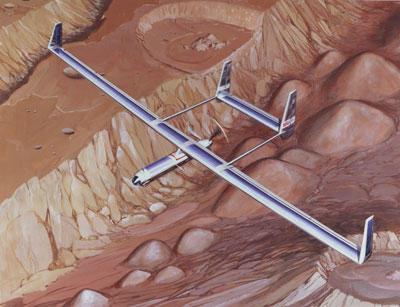

After White Motor Company folded, he got a job for a contractor supplying art to NASA’s Lewis Research Center in Cleveland. He didn’t know much about aviation or space art, but he was a graphic artist, a journeyman artist, used to depicting things that other people described for him. Lewis’ engineers would come to him with their description of some new aircraft or spacecraft design. “They come in and tell you what they want,” he said. “It’s blue collar art.”

(credit: NASA) |

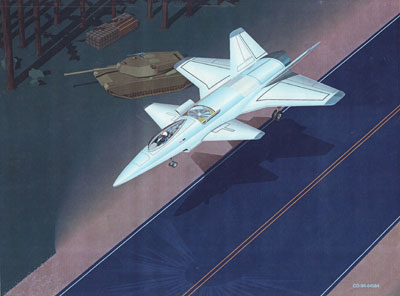

“Very often it’s just a concept… Crude drawings. Some engineers can’t draw as well as children,” he said, laughing. “They’d sketch it out and I in turn would make some sketches and refine it.” He and the engineers would go back and forth, adding and subtracting, changing things. For instance, he pointed to an illustration he made of a vertical take off and landing aircraft. It did not represent a specific design, but rather a concept that engineers at Lewis were working on at the time. The engineer in charge looked at an early version and asked Bossinas to add canards in front of the wings and a large lift fan forward. “And once we were all satisfied, I’d make a rendering,” he explained. A lot of times what they wanted was color artwork to go into a slide presentation or on the cover of a report.

(credit: NASA) |

Most of the work he did in the 1980s involved acrylic paints. But in the 1990s things began to change as the art department adapted to new technology. “They put a computer in our little studio room,” he explained. It was a Mac IIci. “We just ignored it because when you’ve got a deadline on your project you don’t want to tell the guy that it didn’t work or it’s not ready. So we ignored it for awhile.” Finally the company sent over someone to show them how to use the computer. “I was just dumbfounded to see what you could do with that thing,” he said. “I finally committed myself to finish a project with it.” Even though he had been using pencil and paint and canvas for decades, Bossinas was sold on computer illustration from then on. “A lot of people don’t realize that a computer is capable of generating 16 million colors. You and I can only perceive about 252 of them at best. But that’s how precise a computer can be… it was just better all around. You could store your results better. You could change your results with the greatest of ease, you could add and subtract.”

(credit: NASA) |

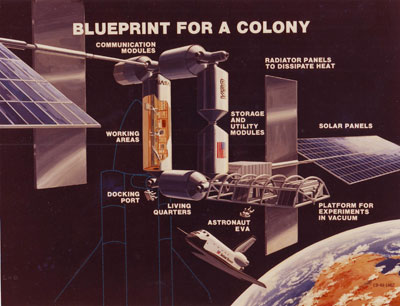

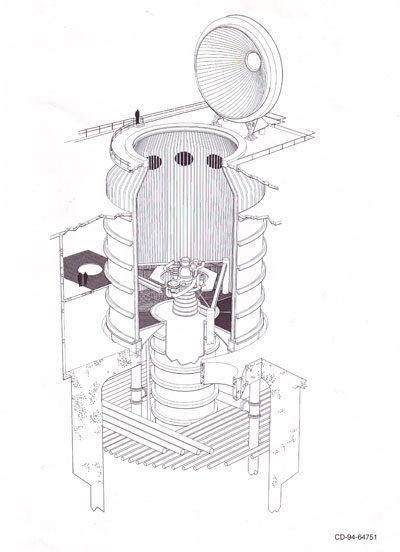

When asked about the difference between an artist and an illustrator, Bossinas furrowed his brow a bit. “It really amounted to both,” he replied. “When I say illustrator… if somebody came in with a fairly precise drawing of what they wanted, then you would have to call that an illustration.” Sometimes his work was very literal, such as creating line drawings of Lewis’ facilities like rocket test stands and vacuum chambers. He was an artist when somebody needed a more generic painting of a moonbase or a space station—not necessarily something that they were building or wanted to build, but representative of the general idea they were trying to convey. Sometimes he took his cues on this from other space artists.

(credit: NASA) |

Les Bossinas retired from Glenn earlier this decade, although he still occasionally does some commercial work if a customer comes along who needs his services. But the same computers that have proven so powerful for artists have also proven powerful for non-artists as well. One of the problems for graphic artists today is that anybody can go online and purchase a program with thousands of images licensed for commercial and private use, rather than hiring a local artist.

(credit: NASA) |

He doesn’t paint for fun, but he teaches art classes at a local senior center and enjoys that. “It’s therapeutic for people to put their nose to a canvas,” he said. “It clears the mind.”

(credit: NASA) |