|

|

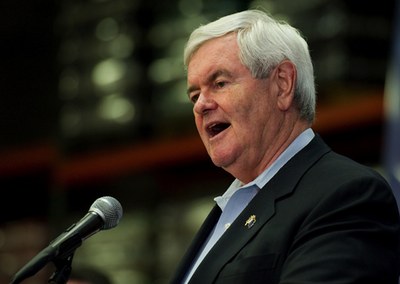

Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich (above) is the only major Republican presidential candidate who has discussed space policy in detail so far during the 2012 campaign. (credit: Newt2012) |

Where the candidates stand on space in 2012

by Jeff Foust

Tuesday, January 3, 2012

The 2012 presidential campaign seems like it has been going on for months, if not years, but today it really starts to count. Tonight thousands of Iowans will gather at caucus meetings across the state to select delegates in the first electoral event of the campaign, to be followed a week later by the first primary, in New Hampshire. The various speeches, debates, ads, and media interviews in the months leading up to now have allowed the candidates to discuss a wide range of topics, from the economy to foreign policy to social issues. But what about space?

As in the 2004 and 2008 campaigns (see “Democratic presidential candidates and space: a primer”, January 12, 2004; and “Where the candidates stand on space”, December 31, 2007), The Space Review contacted the campaigns of the leading candidates in the 2012 presidential race. With no Democrats running against President Barack Obama, whose space policy positions are well known through his administration’s actions over the last three years, this effort focused on the seven major Republican candidates currently seeking the GOP nomination: Congresswoman Michele Bachmann of Minnesota, former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, former Ambassador to China Jon Huntsman, Congressman Ron Paul of Texas, Governor Rick Perry of Texas, former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney, and former Senator Rick Santorum of Pennsylvania.

The Space Review contacted all seven campaigns last month and provided them with a brief list of questions regarding their views on civil and military space policy, including what, if anything, they would do differently if elected president in November. Unfortunately, none of the seven campaigns responded by the time this article was prepared for publication. Instead, this article will instead focus on what the public statements and voting records of the candidates reveal about their space positions—which, in most cases, is very little.

The frontrunner who is outspoken on space

One candidate who has spoken the most about space policy during the campaign to date is a recent frontrunner: Newt Gingrich. His interest in space dates back decades, and includes founding the Congressional Space Caucus in the early 1980s and serving as a member of the Board of Governors of the National Space Society. In several debates and campaign appearances over the last several months Gingrich, in response to questions and sometimes of his own volition, has brought up space policy.

Gingrich has made it clear that he is not a supporter of the space agency as it currently operates, perceiving it as bureaucratic and sluggish. “NASA has become an absolute case study in why bureaucracy can’t innovate,” he said in a June debate in New Hampshire, responding to an audience question about the future of space exploration. Had the money allocated to NASA in the four decades since the Apollo lunar landings been properly spent, he claimed, the country would have a lunar base and several space stations. “Instead, what we’ve had is bureaucracy after bureaucracy after bureaucracy, and failure after failure.”

Gingrich was similarly critical of NASA last month during a Lincoln-Douglas debate in New Hampshire with Jon Huntsman, mentioning the specific case of the gap in NASA access to the International Space Station with the retirement earlier in the year of the Space Shuttle. “Has it occurred to you to wonder what the billions are for and what the thousands of employees are doing? They sit around and they think space,” he said, a line that triggered laughter from the audience.

His disdain of NASA bureaucracy extends to one of the agency’s major programs, the Space Launch System (SLS) heavy-lift rocket. “I think it is disgraceful the way getting into space has been turned into a political pork-barrel. It’s an abuse of the taxpayer and an abuse of America’s future,” he said when asked about the SLS at a town hall meeting in Dallas in October.

Gingrich, who in the past has endorsed the idea of very large prizes—in the billions of dollars—to incentivize the private sector to undertake missions as ambitious as human expeditions to Mars, has suggested he would support something similar in the areas of space transportation and exploration. “If you had taken 5 or 10 percent of the NASA budget in the last decade and put it into a prize for the first people to get to the Moon permanently, you’d have 20 or 30 folks out there getting to the Moon, we’d already be on the Moon, and the energy level would be unbelievable,” he said at the Dallas meeting.

Interviewed by an Orlando television station in October, Gingrich also endorsed the idea of a large prize to accelerate the development of vehicles to transport astronauts to the ISS. “I think that we frankly ought to right now have a crash program, put up a big prize, challenge the private sector, and get back into space within two years, and in an aggressive way,” he told Central Florida News 13.

Gingrich’s support of commercial space efforts in lieu of large government programs puts him in the unusual situation of endorsing the policy of the policy of the man he seeks to defeat in November. Shortly after the Obama Administration rolled out its proposed new direction for NASA in February 2010, Gingrich and Robert Walker—a former congressman and chairman of the House Science Committee who now works as a lobbyist—penned an op-ed in the Washington Times praising it, calling it a “brave reboot” of the space agency that “deserves strong approval from Republicans.”

Gingrich, at the June debate in New Hampshire, said he didn’t want to get rid of space program, only restructure it to make it more effective. “It’s not about getting rid of the space program, it’s about getting to a real space program that works.”

The frontrunner who says little about space

Gingrich is one of a series of candidates who have risen in the polls in the last several months, only to lose support for one reason or another. (Indeed, Gingrich’s support has been slipping in the last few weeks, while Rick Santorum has experienced a surge, at least in Iowa.) Throughout that time, however, Mitt Romney has remained near the top of polls both nationally and in key early states, support that has recently solidified.

Unlike Gingrich, though, Romney has said little about space. In the same June debate where Gingrich talked about “getting to a real space program”, Romney jumped in near the end of conversation with a comment tangentially related, at best, to the question. “I think fundamentally there are some people—and most of them are Democrats, but not all—who really believe that the government knows how to do things better than the private sector,” he said, without specifying how that related to space policy.

While Romney has no space-related track record from his limited time in office—one term as governor of Massachusetts from 2002 through 2006—he did run for president in 2008, and made a few statements about space policy during that run for office. Campaigning in Florida in January 2008, prior to that state’s primary, Romney offered an endorsement of the Bush Administration’s Vision for Space Exploration, but declined to commit to increasing NASA’s budget in order to shorten the post-Shuttle gap. “I’m prepared to study it very thoroughly, and I’m not prepared to make commitments without having studied things,” he said at time.

However, in the last month Romney has brought up space in interviews and in one debate, but only to criticize Gingrich, rather than discuss his own space policy views. That approach appeared to stem from a column by David Brooks of the New York Times on December 8, where he mentions that Gingrich had endorsed the concept of “a permanent lunar colony to exploit the Moon’s resources” as well as “a mirror system in space” to provide nighttime lighting. Gingrich had not mentioned either project during his campaign; Brooks appeared to get those ideas from the book Window of Opportunity written by Gingrich and published in 1984.

In a December 10 debate in Des Moines, Iowa, Romney brought up the lunar colonies idea when asked how he differed with Gingrich on the issues. “We could start with his idea to have a lunar colony that would mine minerals from the Moon,” Romney said. “I’m not in favor of spending that kind of money to do that.” Two days later, in a video interview with POLITICO, Romney suggested that Gingrich’s support for a lunar colony would hurt his chances to beat President Obama in November if he won the GOP nomination. “The idea of a lunar colony? I think that’s going to be a problem in the general election,” Romney said.

The rest of the pack

The remaining five candidates—Bachmann, Huntsman, Paul, Perry, and Santorum—have said virtually nothing about space during the course of the campaign to date. In a few cases, though, the candidates have modest track records on space issues.

Bachmann and Paul, who are both current members of the House of Representatives, have voted on a handful of bills in recent years directly related to civil and commercial space policy. In September 2010 Bachmann voted for, and Paul voted against, the NASA Authorization Act of 2010, the bill that enacted a number of key elements of the Obama Administration’s new NASA policy while also mandating the development of the SLS. However, in June 2008 Bachmann also voted for the NASA Authorization Act of 2008, which endorsed the Bush Administration’s Vision for Space Exploration, while Paul was one of only 15 House members who voted against the bill. In November 2004 Paul did vote for the Commercial Space Launch Amendments Act of 2004 after earlier in the year being the only member to vote against a previous version of the legislation (Bachmann was not yet a member of Congress at the time that bill was considered.)

Paul’s rejection of the two NASA authorization bills may be based on the libertarian roots of his personal political philosophy. A recent AP article noted that, after Congressional redistricting put Paul’s district near the Johnson Space Center, a group of Houston businesspeople approached Paul to offer “a primer on the value of the space shuttle.” The response they reportedly got from Paul: “space travel isn’t in the Constitution.” However, in February 2010 Paul was one of 27 members of Congress who signed a letter to NASA administrator Charles Bolden asking him to take no action to terminate the Constellation program until Congress acted on the administration’s proposal.

The voting record of Santorum, who was first elected to the Senate in 1994 and served through 2006, is even older and thinner. Part of that is because many space-specific pieces of legislation are uncontroversial enough to pass the Senate by unanimous consent, leaving no paper trail of roll call votes or floor speeches. Perhaps the most recent voting record he left related to space policy was in July 1998, when he voted on an amendment to an appropriations bill that would have terminated the ISS. Santorum was among 66 senators who voted against the amendment, which effectively marked the end of efforts to kill the space station.

As governors, Huntsman and Perry have had little opportunity to weigh in on space policy. However, after the landing of Atlantis in July on the final shuttle mission, Perry—at the time not yet a candidate for president—issued a press release from the governor’s office criticizing the administration for shutting down the shuttle program without a replacement vehicle in place. “It is time to restore NASA to its core purpose of manned space exploration, and to define our vision for 21st Century space exploration, not in terms of what we cannot do, but instead in terms of what we will do,” he said in the statement, without offering specifics about how to accomplish that.

Huntsman has not discussed space policy on the campaign trail, but suggested shortly after declaring his candidacy in June that he would do so at some point. “We always want to be at the cutting edge of space flight. Today it’s an affordability issue,” he said, according to an Orlando Sentinel report on the opening of his national campaign headquarters in central Florida. “When we get around to space policy, we’ll come down here and make sure people are fully aware of what our hopes are.”

The Cain Maneuver

With the Florida primaries coming up at the end of this month, there may be renewed opportunities for candidates to speak out on space issues, particularly when they campaign in Florida’s Space Coast region. Nonetheless, it remains possible that the eventual nominee may be someone who has spent little time discussing his or her space policy, focusing instead on other issues of greater importance to larger portions of the electorate.

The experience of one candidate no longer in the race, though, offers a model of how such a nominee could still use space as at least a rhetorical point during the general election. At the apex of his campaign in October and November, Georgia businessman Herman Cain—who dropped out of the race a month ago after allegations of marital infidelity—brought up space on the campaign trail. Speaking in Alabama in late October, he complained that President Obama “has cut our space program to the point that we now have to bum a ride with the Russians in order to get to outer space,” according to one account of the event. At another campaign event there, Cain said he was “disappointed when President Obama decided to cut a significant part of the space program.”

In those appearances, as well as one a couple weeks later in Georgia, Cain vowed that he would reverse those developments. “I can tell you that as president of the United States, we are not going to bum a ride to outer space with Russia,” he said in the Georgia speech. “We’re going to regain our rightful place in terms of technology, space technology.”

Cain didn’t describe how exactly he would “regain our rightful place” in space technology to avoid any continued reliance on Russia, and he dropped out of the race before he could elaborate. That rhetoric, though, could serve a model to a Republican nominee who wishes to criticize the administration’s space policy but doesn’t have the time or interest to formulate a detailed alternative policy. Such a tactic would be incomplete and even inaccurate—the decision to retire the Space Shuttle, after all, dates back to the Bush Administration in 2004—but could prove effective in winning support in some key areas, like Florida.

In 2008, voters were treated to a rare surfeit of information about the candidates’ positions on space, including debates and detailed position papers by both the Obama campaign and his Republican opponent, Senator John McCain of Arizona (see “Space policy heats up this summer”, The Space Review, August 18, 2008). This time around, though, with the Obama Administration’s policy already in place and much bigger campaign issues, like the health of the economy, to deal with, the campaign may return to its historical norms of piecemeal information on space, leaving space enthusiasts to sift through volumes of campaign rhetoric to look for any new policy initiatives proposed by the candidates.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site and the Space Politics and NewSpace Journal weblogs. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone, and do not represent the official positions of any organization or company, including the Futron Corporation, the author’s employer.

|

|