|

|

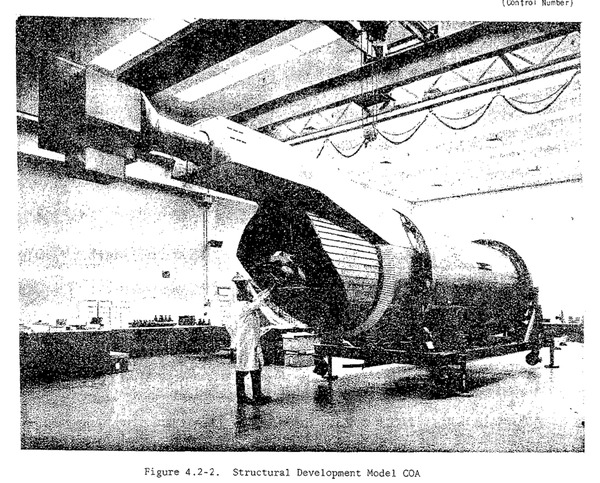

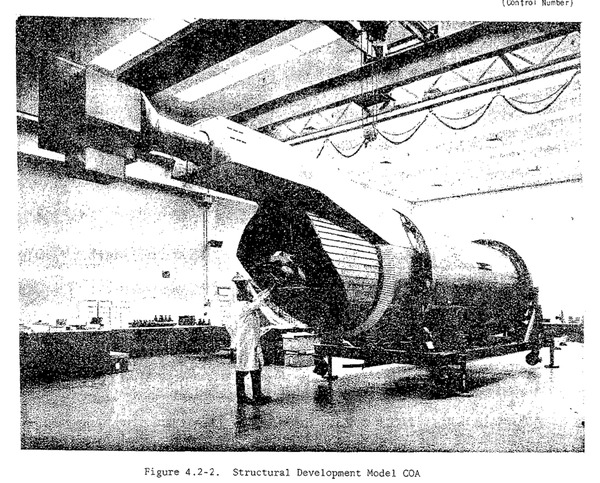

Elements of the Manned Orbital Laboratory under construction in the 1960s. (credit: USAF) |

Big Black Bird

by Dwayne A. Day

Monday, July 14, 2014

After five decades of secrecy, the details of the 1960s-era Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) program are finally being revealed.

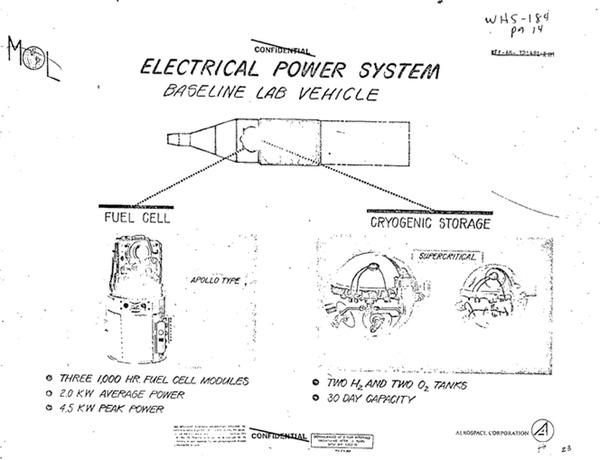

MOL was started in late 1963 but did not get a formal approval from President Lyndon Johnson until 1965. Publicly, it was a two-person military space station program to conduct experiments to determine what military missions humans could accomplish in space.

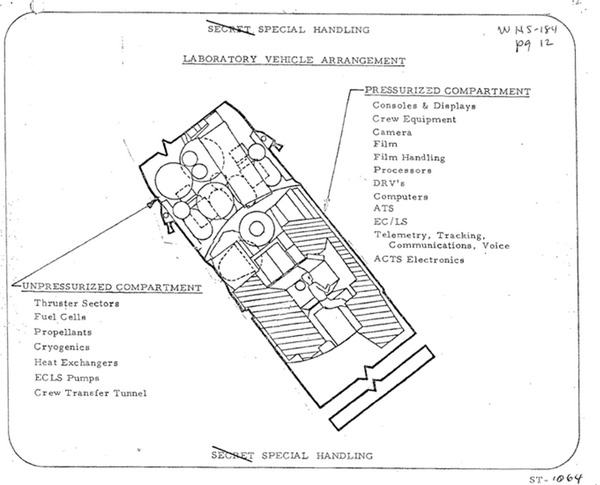

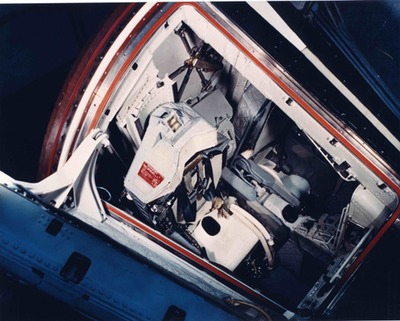

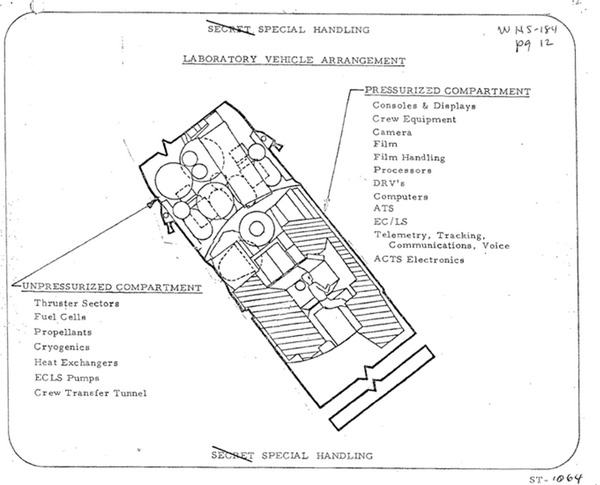

But MOL had a highly classified operational mission—collecting intelligence. The code name for that mission was “DORIAN.” The heart of the mission was a large camera system known as the KH-10, which was mounted in the unpressurized section of the spacecraft.

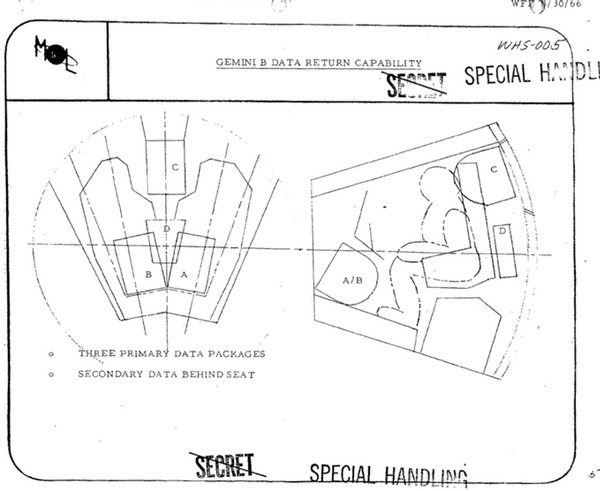

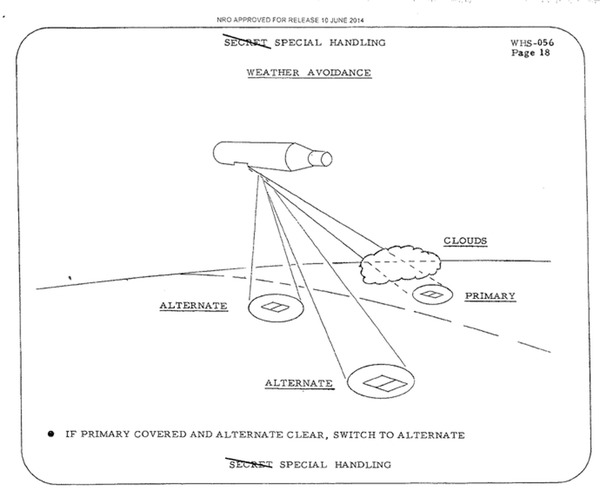

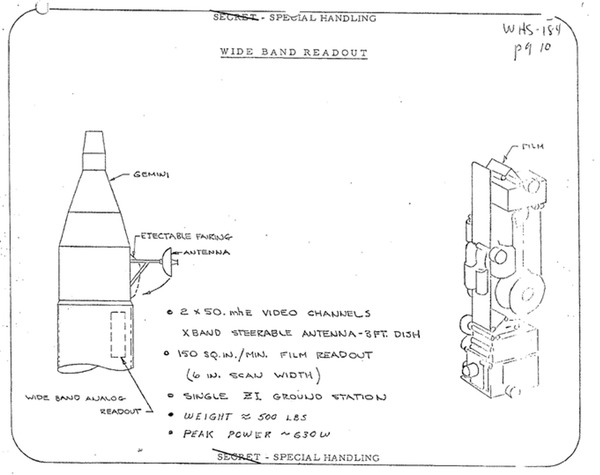

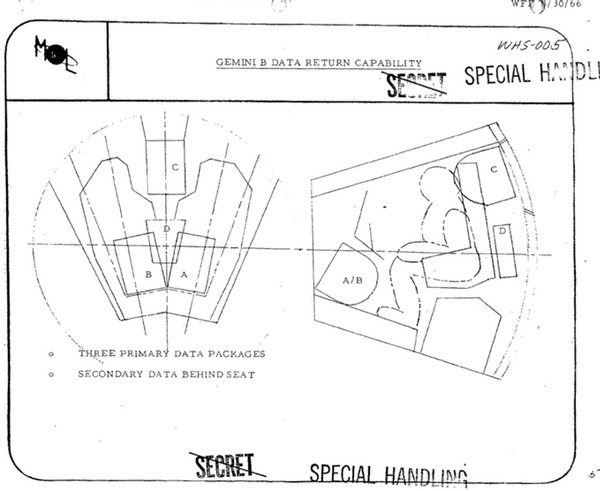

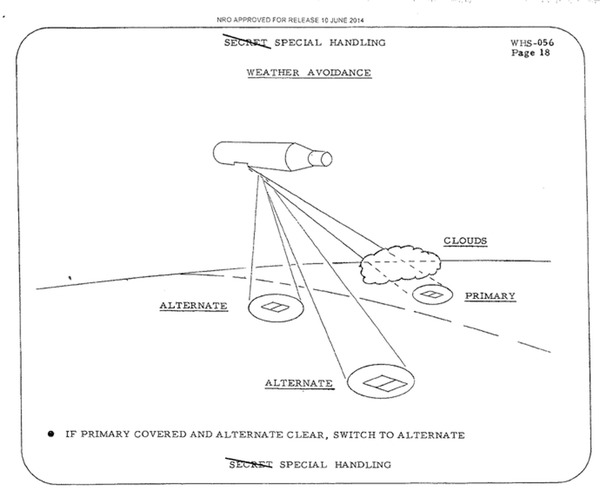

The plan was for the astronauts to look through viewfinders on their spacecraft at targets on Earth and take photos of interesting ones with the powerful KH-10. They could switch from cloud-covered targets to those that were free of clouds, and report to the ground what they saw. The camera used film, and that film could either be returned to Earth in a small reentry capsule that was mounted on the side of their spacecraft, or it could be wound up into “data storage packages” that the astronauts would then have to cram into their cramped Gemini spacecraft for their return home at the end of their 30-day mission.

|

|

Mixing humans and big optics is a risky proposition for many reasons. Humans require many systems to keep them alive. Those systems, including circulation fans, can create vibrations that can affect the optics. In addition, a camera system that requires humans to interact with it instead of simply taking photos also adds requirements. For instance, the big robotic reconnaissance cameras that the United States National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) was developing in the 1960s only had to focus their image on the film. In contrast, the KH-10 had additional optics that could split off the image to a viewfinder, inside the pressurized MOL crew cabin, as well as the film. This mass and complexity was not required if the people could simply be eliminated.

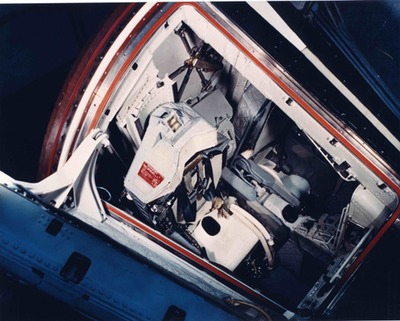

The cockpit of a Gemini spacecraft that would have been used to transport astronauts to and from MOL. (credit: USAF) |

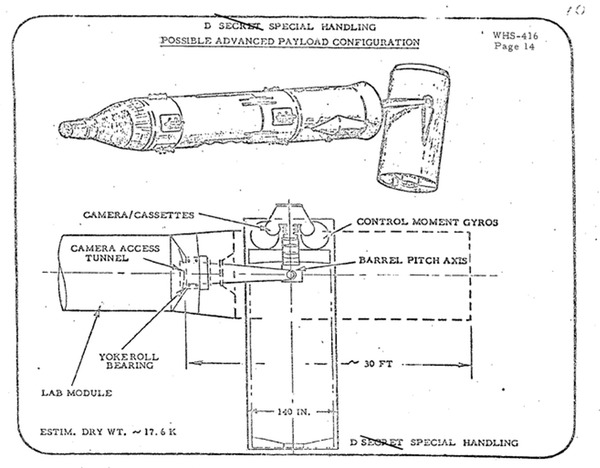

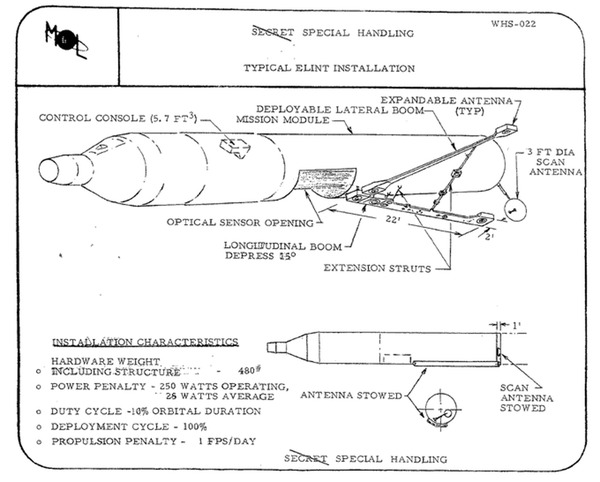

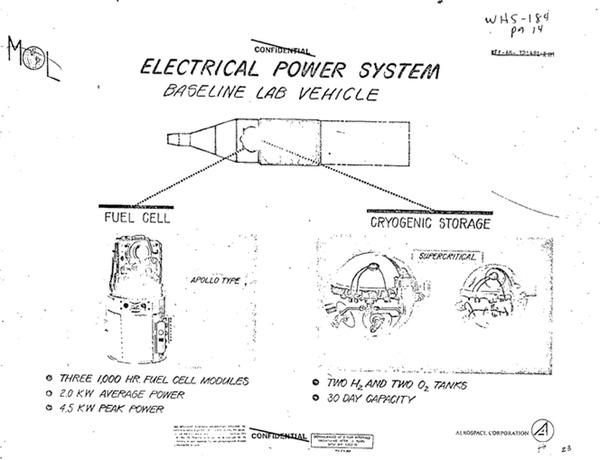

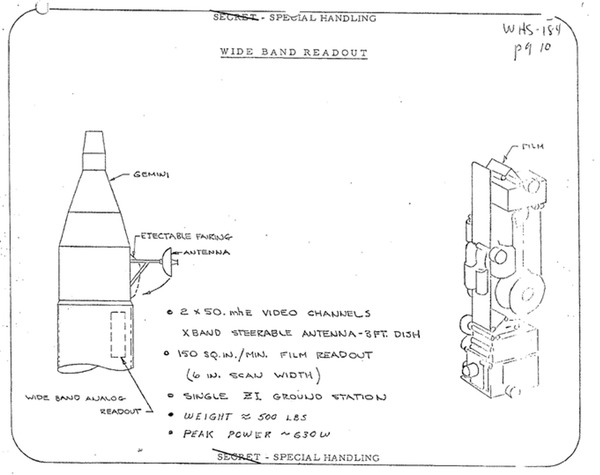

Although the camera was the primary intelligence mission, MOL also had a mission for collecting electronic intelligence, or elint, using antennas to gather up signals from Soviet radar sites and possibly even communications. Other missions included ocean surveillance, some kind of radar imaging, satellite inspection, and a near real-time imagery readout capability. MOL was planned as a series of at least a half-dozen missions that had eventually slipped to 1972. The newly emerging information on MOL does not yet clarify what each mission would do, although new tasks and experiments would be added as the program progressed. MOL contractors also explored more advanced versions of MOL, including one with a semi-detached camera system.

|

|

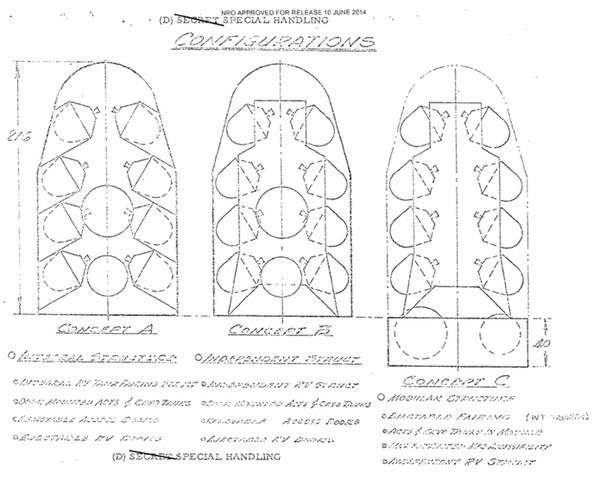

Because of the complications of adding humans to the mission, soon after the program started the spacecraft designers were also told to begin evaluating an unmanned MOL that could carry from six to eight reentry vehicles for return to Earth. According to a number of recently declassified sketches, the design of this unmanned MOL advanced considerably, although the piloted version was always the primary goal. The Air Force even selected astronauts for the program and put them through an extensive training process.

|

|

MOL was canceled in summer 1969 by Richard Nixon. By this time the project had slipped its schedule and was increasingly expensive. The US military was already engaged in a costly war in Southeast Asia, and MOL was also in competition against another expensive reconnaissance program known as the KH-9 HEXAGON. Nixon killed MOL to save money, but the program was increasingly anachronistic at a time when robotic reconnaissance systems regularly demonstrated their capabilities. Had MOL actually flown, it would have provided interesting and valuable information on longer-duration human spaceflight before NASA flew Skylab. But secrecy may have prevented some of this information from being properly transmitted. Finally, 45 years later, we are now able to tell much more of the story of the big classified space station that never reached orbit.

Dwayne Day can be reached at zirconic1@cox.net.

|

|