They did it: New Horizons flies past Plutoby Jeff Foust

|

| “There is a little bit of drama because this is true exploration. New Horizons is flying into the unknown,” Stern said. |

That doesn’t mean, though, that a flyby mission is any less nerve-wracking. While Mars landers like Curiosity have their “seven minutes of terror,” those involved with, or otherwise following, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, had hours of anticipation last week. As New Horizons made its closest approach on the morning of July 14, they celebrated, and then waited for thirteen hours to find out if the spacecraft had indeed worked as planned.

Members of the New Horizons mission team stand on stage at the Applied Physics Lab during the post-contact flyby. NASA administrator Charles Bolden is at the podium. (credit: J. Foust) |

The reason for the split celebrations was the nature of the flyby. At the time of closest approach—7:49 am EDT, when the spacecraft passed 12,500 kilometers above the surface of Pluto—the spacecraft was out of contact with the Earth. The spacecraft’s design prevented it from pointing its antenna at Earth while also turning its instruments toward Pluto and its moons. (Even if it had, it would have taken four and a half hours for those signals to arrive at Earth, given Pluto’s distance of about five billion kilometers.

Nonetheless, those attending events at the Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Maryland, mission control for New Horizons, celebrated that moment of closest approach. A crowd gathered to countdown the final seconds before closest approach, followed by cheering, American flag waving, and even a halfhearted “U-S-A!” chant.

The assumption was that New Horizons was working as planned, collecting images, spectra, and other data during the flyby. There was, though, no way to know that the spacecraft was healthy: its last communication with Earth ended the previous evening, as planned, and the next communications window didn’t open that evening. The spacecraft could have suffered a problem like the computer glitch that put the spacecraft into safe mode earlier in the month. Or, worse, the spacecraft could have encountered debris that damaged or disabled the spacecraft.

Mission officials were confident that would not happen. The spacecraft was operating in a special “encounter mode” designed to keep the spacecraft from locking up in safe mode if it had a problem. Previous searches failed to turn up any sign of dust or debris that posed a risk to the spacecraft. But, the uncertainty remained.

“There is a little bit of drama because this is true exploration. New Horizons is flying into the unknown,” Alan Stern, principal investigator for the mission, said at a NASA press conference held shortly after that closest approach. But, he added, “I don’t think that we’re going to lose the spacecraft.”

“We always talk about the spacecraft being a child,” said Alice Bowman, the mission operations manger, or MOM, for New Horizons. “We lost signal as planned last night, at 11:17, and there was absolutely nothing anything on the operations team could do, just to trust that we had prepared it well, to set off on its journey on its own and do what it needed to do.” She added she had “absolute confidence” the spacecraft would operate as planned and contact Earth that evening.

Until then, there was not much for people to do but to wait for that signal. During the day, NASA and APL organized a series of briefings about the mission, including discussions of some of the data the spacecraft returned prior to closest approach. Scientists were intrigued, but also held off on too much speculation, because the data that New Horizons was collecting that day would be far better than what they had in their hands at the moment.

Bowman, who had gotten just an hour of sleep the night before, said later that, during the wait, she took a half-hour nap. She passed the time doing some more mundane things, like catching up on email. “You all know how email is,” she said.

Finally, that evening, crowds gathered again at APL, filling an auditorium and adjacent ballroom at the APL conference center. All eyes were on the NASA TV feed, looking into mission control elsewhere at APL, waiting for New Horizons to phone home.

“Okay, we’re in lock with carrier,” Bowman said from mission control, the first sign that New Horizons was transmitting. In the auditorium, there were a few claps.

“We’re in lock with symbols,” she said moments later, followed quickly by, “We’re in lock with telemetry with the spacecraft.” Telemetry data from New Horizons was now flowing through the Deep Space Network (DSN) to the consoles at mission control, giving engineers the opportunity to determine the health of the spacecraft. The auditorium erupted in cheers. New Horizons, at least, was alive and transmitting.

| “I’d like to characterize that DSN pass you just watched as one small step for New Horizons, and one giant leap for mankind.” |

Engineers quickly reviewed the data they had: normal power from the communications system, no evidence of “autonomy rules” that would have been signs of glitches during the flyby, solid state data recorders with the expected amount of data in them, and more. Each announcement from the engineers, with a steady stream of “nominal” responses, was greeted with applause in the auditorium.

“Okay,” Bowman said after the last series of reports, followed by the briefest of pauses. “PI, MOM on Pluto One,” she said on the communications loop to Stern. “We have a healthy spacecraft. We’ve recorded data of the Pluto system, and we’re outbound from Pluto.” That set off another round of cheering in the auditorium.

About a half-hour later, the post-contact press conference took place at APL. But, in reality, the event was more of a victory rally. In a scene reminiscent of the post-landing briefing at JPL after Curiosity touched down on Mars in August 2012, the New Horizons team streamed into the auditorium, wearing matching black polo shirts with the mission emblem. They received sustained cheers from most of the auditorium—press excepted—for several minutes before the briefing/rally got started.

“What a phenomenal day,” NASA administrator Charles Bolden said, a statement that seemed, if anything like a bit of an understatement in the raucous room. Members of the project team, he suggested, “are not aware of what an incredibly historic day this has been in many regards. What’s really, really important for the team to understand is that they were on the front page, they were in the headlines, they were on the news all day long in spite of everything else going on the in the world.”

(That was, in retrospect, not strictly true. The front page of at least some editions of Wednesday’s Washington Post, to give one example, was devoted to the completion of a nuclear deal with Iran. The flyby was relegated to page 2.)

“I’ve never been one to underplay the significance of this mission,” Stern said to laughter. “I’d like to characterize that DSN pass you just watched as one small step for New Horizons, and one giant leap for mankind.”

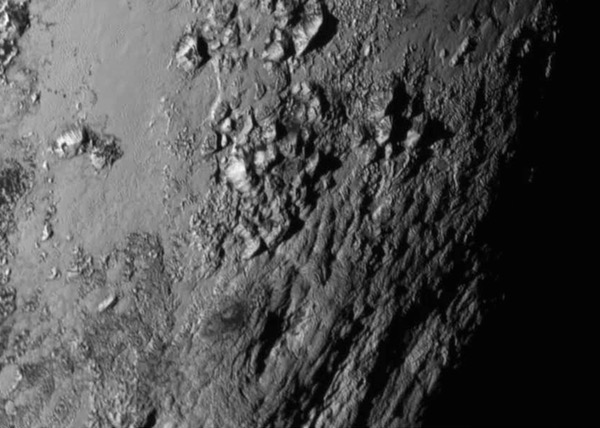

A high-resolution image of a portion of Pluto's surface revealed mountains made of ice more than 3,000 meters high. (credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI) |

That brief communications session Tuesday night provided engineering data only: an update on the health of the spacecraft, but no images or other science data. That would have to wait until early the next day, when the spacecraft transmitted a very small subset of the data it collected during the flyby, including some high-resolution images of parts of Pluto and its largest moon, Charon.

At a press conference later Wednesday, just nine hours after that downlink started, project scientists expressed their delight, and surprise, at what the spacecraft returned. “I am completely surprised,” said Stern at the APL press briefing. “I don’t think any one of us could have imagined that it was this good.”

What was immediately surprising to Stern and his colleagues was the evidence of relatively recent geological activity on both Pluto and Charon. A high-resolution image of Pluto, through part of the heart-shaped region that scientists are now informally calling Tombaugh Regio after Pluto’s discoverer, Clyde Tombaugh, showed a distinct lack of impact craters. That led scientists to conclude it must be less than 100 million years old: relatively young in a geological context. It also revealed a range of mountains, most likely made of water ice, more than 3,300 meters tall.

Charon did not disappoint either. Images returned in the days before closest approach showed a dark, smooth region. Newer images showed a series of troughs and cliffs running across the moon for nearly 1,000 kilometers, as well as a canyon on the limb of Charon as seen by New Horizons that scientists estimate is up to ten kilometers deep.

“We've settled the fact that these very small planets can be very active after a long time,” Stern said. “It’s going to send a lot of geophysicists back to the drawing boards, trying to understand how exactly you do that.”

| “Speculating now would be especially embarrassing, as we could be proven wrong very quickly,” Spencer said. |

Geologic activity has been seen on other icy worlds of similar size, from the plumes on Neptune’s moon Triton to the jagged surface of Europa that covers a subsurface ocean of liquid water. However, those worlds are all moons of giant planets, whose interiors are warmed by tidal heating as they orbit those planets. That mechanism doesn’t work for Pluto and Charon.

John Spencer of the Southwest Research Institute, one of the scientists involved with New Horizons, suggested two possible mechanisms for internal heating of Pluto and Charon. They may have radioactive elements in their silicate cores, whose decay heats them. Or, he offered, they may have subsurface oceans that are freezing out, liberating heat in the process.

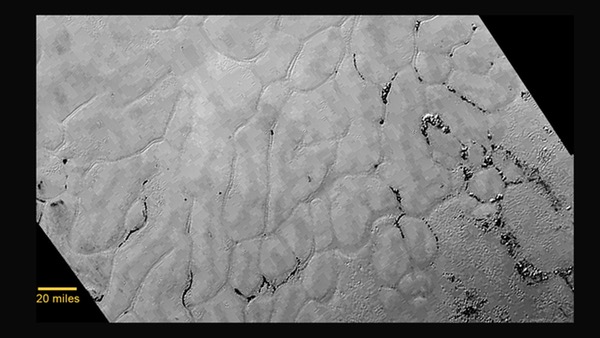

An image of Sputnik Planum shows a terrain of hills with few craters, suggesting the area is geologically very young. (credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI) |

But there’s no evidence right now to support either hypothesis, or other explanations, and sleep-deprived scientists who had only hours to review the data were hesitant to go too far out on any limbs, particularly with much more data yet to come. “Speculating now would be especially embarrassing, as we could be proven wrong very quickly,” Spencer said.

Additional data returned in the following two days, and presented at a press conference Friday at NASA Headquarters, continued to suggest that Pluto in particular remains active. An image of a plain with Tombaugh Regio, dubbed Sputnik Planum, showed a series hills about 20 kilometers across, separated by narrow trenches that have darker material in them.

“This terrain is not easy to explain,” said Jeff Moore of NASA’s Ames Research Center, another mission scientist, at the Friday briefing. The terrain could be explained by convection below the surface, or contraction of the surface itself. Whatever it is, it’s a sign the dwarf planet is active. “Pluto is every bit as geologically active as any other place we've seen in the solar system,” he said.

The science, and the surprises, will slowly be coming for many months. Given the spacecraft’s distance and limited power, it can transmit data at a typical rate of just two kilobits per second. That means it will take New Horizons up to 16 months to return all the data it collected in that flyby, first in compressed “browse” formats, then in uncompressed form.

The successful flyby also raised the chances that New Horizons will get to perform an extended mission, flying past a more distant, smaller Kuiper Belt object (KBO) in 2019. The spacecraft is in good health and has enough hydrazine propellant remaining to perform a course correction maneuver later this year to send it towards one of two possible KBOs, project engineers said. However, NASA officials reiterate that a final decision on an extended mission won’t come until the end of the next planetary science “senior review” of extended planetary missions in August or September of next year.

That decision is likely far off in the minds of those involved in the mission, who are still celebrating the success of the flyby and examining the scientific data it is starting to return. At the post-contact briefing Tuesday night, Stern asked everyone involved in the project in one manner or another to stand up.

“I want to say to you just three words,” he said. “We did it.”