Second horizonby Dwayne Day

|

| For several years the NH 2 advocates did not find much enthusiasm for their proposal within the scientific community or NASA, and so soon took their pitch to Capitol Hill in search for a sponsor. |

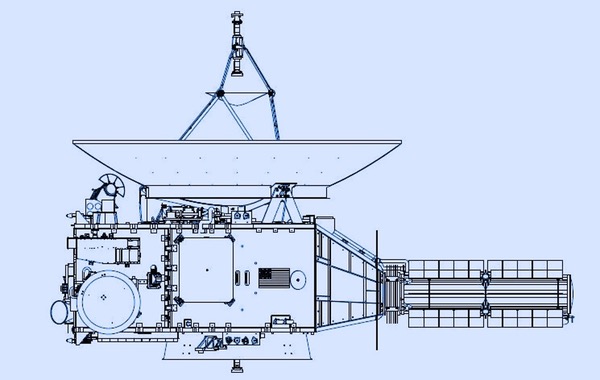

In mid-2002, the team that was developing the New Horizons spacecraft, led by principal investigator Alan Stern, proposed building a second spacecraft which they dubbed New Horizons 2 (NH 2). It would fly past Kuiper Belt Object 1999 TC36 and then later fly past two smaller KBOs. It would also fly past Uranus on its way to the Kuiper Belt, although this was considered a secondary science objective. NH 2 was billed as a backup to New Horizons, using identical systems and instruments and counting on the fact that it is possible to build a second copy of a spacecraft significantly cheaper than the first—perhaps only 60 percent as much—provided that procurement is started at the same time as the first. New Horizons was then scheduled for a 2006 launch, and the group claimed that if NH 2 was started in 2006 it could launch by 2009.

Although the group’s argument was that this spacecraft would be relatively cheap, it had not been identified as a priority by any NASA advisory group and had not appeared in the 2001 planetary science decadal survey. In addition, it would still cost a significant amount of money that was already allocated to other projects in NASA’s budget, meaning that unless NASA received more money, something else would have to be canceled. For several years the NH 2 advocates did not find much enthusiasm for their proposal within the scientific community or NASA, and so soon took their pitch to Capitol Hill in search for a sponsor. Instead of an outright endorsement, in 2004 the Senate Appropriations Committee directed NASA to undertake a study of NH 2.

Stern and his team justified New Horizons 2 as an insurance policy: “The first objective of New Horizons 2 is to provide important backup to the high priority Kuiper Belt Object science that NASA has stated is only a goal and not a requirement for NH 1,” the proposal team wrote in a short proposal paper. They acknowledged that the NH 2 concept did not exist during the 2001 decadal survey process and so it did not appear in the decadal survey. But they also noted: “New Horizons 2’s Uranus 2014 flyby will be a stunning exploration accomplishment in its own right. Beyond bringing far more sophisticated remote sensing instruments and a dust detector to the Uranian system than Voyager did, New Horizons 2 can accomplish a flyby to reconnoiter the Uranus system near equinox, a geometry that allows all of the Uranian system to be explored—something Voyager’s solstice arrival geometry of 1986 was denied. The Uranian equinox opportunity that NH 2 can achieve in 2014 will not reoccur until almost 2050! It is no exaggeration to say that the timing of the NH 2 Uranus-KBO exploration combination is literally once in a lifetime.” The decadal survey had not considered a Uranus mission, but it soundly rejected a similar Neptune-Triton flyby mission.

According to Alan Stern, the Senate committee had “noted that New Horizons II is needed to satisfy the key goal of the planetary decadal survey with regard to Kuiper Belt exploration ‘to sample the diversity of bodies in the Belt.’” But in actuality the Senate committee had not endorsed the mission, but instead merely called for a study, stating: “NASA is directed to undertake a detailed study of the feasibility for a New Horizons II mission, to be launched within the near-term, if the study results can justify the scientific return for such a follow-on mission, at a price considerably less than the original New Horizons mission. Such a study should have its results submitted to the Committees on Appropriations by April 15, 2005.”

In response to the Senate report, NASA chartered a panel to address the issue and directed it to consider one or more of the following possible missions:

- further survey of the Pluto-Charon system

- further survey of Kuiper Belt Objects

- survey of objects believed to be captured Kuiper Belt Objects (for example, Neptune’s moon, Triton)

The panel was specifically tasked with answering the following questions:

- Considering that the New Horizons mission was competed, determine whether New Horizons 2 should also be competed.

- Determine whether such a mission can be developed and launched “within the near term.”

- Determine whether the potential science return can be justified for such a mission.

- Determine whether such a mission can be developed and launched at a cost “considerably less” than that of New Horizons.

In answering these questions, the panel was given latitude as to how to define “near term” and “considerably less than.”

| The New Horizons 2 proposal was an effort to gain approval for a mission that was not recommended by the planetary science decadal survey or any other independent group. |

The panel started working in February 2005 and delivered their report to NASA by March 31. The report stated that the lack of availability of an radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) for the mission and the need for Pu-238 heat sources for the RTG would prevent launches prior to mid-2011, which meant it was not a “near term” mission. The panel also concluded that because launch was not imminent, the mission should be competed—in other words, the New Horizons team would have to compete with other proposers rather than simply being approved to build a second spacecraft, thus undercutting the claim that it could be a less expensive copy.

Stern and his teammates had proposed NH 2 based upon the argument that it could be done for considerably less cost than New Horizons. At the time, the projected cost for New Horizons was $723 million, and the panel concluded that a second spacecraft would cost about $100 million less, which panel members concluded was not “considerably less.”

The New Horizons 2 proposal was an effort to gain approval for a mission that was not recommended by the planetary science decadal survey or any other independent group. But the NASA review panel recommended that any New Horizons 2 proposal should also be reviewed by the National Research Council’s Committee on Planetary and Lunar Exploration, or COMPLEX, which was considered to be the “the keeper of the decadal.” No such review occurred and New Horizons 2 was soon forgotten.