A one-year recap of CCtCapby Jeff Foust

|

Boeing’s John Mulholland, Chris Ferguson, and John Elbon, and Kennedy Space Center director Robert Cabana, pose in front of CST-100 hardware at Boeing’s new Commercial Crew and Cargo Processing Facility at KSC. (credit: J. Foust) |

The most visible milestone in recent months in the commercial crew program was not, strictly speaking, a CCtCap contract milestone. On September 4, Boeing invited guests to a ceremony marking the grand opening of its Commercial Crew and Cargo Processing Facility (C3PF) at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center. That building, formerly the Orbiter Processing Facility 3 during the shuttle program, will be where Boeing’s CST-100 spacecraft are assembled and prepared for flight.

| “Today, we’re in the middle of producing the structural test article” for the CST-100, said Boeing’s Mulholland. |

That event drew a range of high-profile speakers, including NASA administrator Charles Bolden, Florida governor Rick Scott, and Sen. Bill Nelson (D-FL). They were all singing the praises of the commercial crew program in general and, more specifically, Boeing’s decision to establish the C3PF in Florida, a decision that will eventually mean 550 jobs for the region.

Boeing already has hardware in the C3PF. “Today, we’re in the middle of producing the structural test article,” said John Mulholland, Boeing’s vice president for commercial programs and manager of the company’s commercial crew effort. That included elements of the crew module and service module, which will be completed early next year and shipped to California for testing.

Components for a second CST-100, called a qualification or “qual” test vehicle, will be arriving in December and January for assembly, he said. “We really now have a clear path to regaining domestic US human launch capability. It’s going to be exciting,” he said.

In a briefing with reporters the day before the C3PF event, Mulholland laid out the series of CST-100 test flights the company is planning for 2017. In May of that year, Boeing plans to launch a CST-100 on an uncrewed test flight; that spacecraft will be built after the qual vehicle is completed next year. In August, Boeing will use the qual vehicle for a pad abort test, similar to the one SpaceX carried out earlier this year. In September, CST-100 will fly a crewed test flight to the ISS, carrying one NASA astronaut and one Boeing test pilot. Assuming all those flights are successful, Boeing would be ready for the first operational, or “post-certification mission,” CST-100 flight in December 2017.

Notably absent from that list of milestones is an in-flight abort test, which SpaceX is planning to perform. Mulholland said they will get better data from simulations and wind tunnel tests than if they did a one-off—and expensive—in-flight abort. “It’s literally hundreds of thousands of data points that you need to adequately analyze and certify your vehicle,” he said. An in-flight test provides “one confidence test of your in-flight system, but it doesn’t really buy down the risk of the entire certification envelope.”

Besides the opening of the C3PF, Boeing and its launch provider, United Launch Alliance, are making progress on another piece of infrastructure needed for CST-100 launches. Last week, the first parts of the crew access tower arrived at Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral, the Atlas V launch pad. The tower, allowing astronauts to enter the spacecraft once rolled out to the pad, will be built in segments between Atlas launches.

There was one bit of news from the C3PF grand opening. “We get asked a lot, ‘When are you going to pick a name for that wonderful spacecraft?’” said Chris Ferguson, the former NASA astronaut who serves as Boeing’s director of crew and mission operations. Evidently, CST-100 alone didn’t cut it.

That new name, Ferguson announced at the end of the grand opening event, was CST-100 Starliner. “When we chose a name for the CST-100, we wanted to choose something that gave a nod to the next generation of space, and the next 100 years of flight at Boeing,” he said. That’s a reference to Boeing’s centennial in 2016, and the company’s history of aircraft that included the 787 Dreamliner and the 307 Stratoliner.

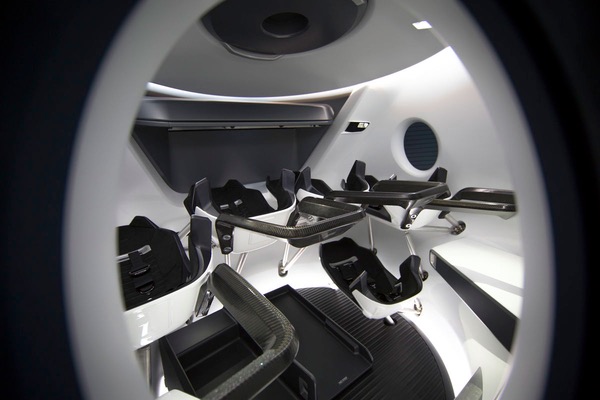

A view of the interior of SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft, released by the company last week. (credit: SpaceX) |

SpaceX, the other company with a CCtCap contract, also showed off a little bit of its progress last week, albeit online rather that in an in-person event. The company released pictures of the interior of its Crew Dragon vehicle it is developing, along with a brief video.

| Development of Dragon is on track for a series of test flights starting late next year, SpaceX’s Koenigsmann, includinf an uncrewed test flight launching at the “end of ’16-ish.” |

The interior has many of the same features as the mockup of what was then called Dragon v2 last year (see “Decision time for commercial crew”, The Space Review, June 2, 2014), including large computer displays. One notable difference was the seating: the leather-like upholstery of the v2 is now replaced with “Alcantara cloth,” a synthetic suede-like material often used in luxury cars. And while the v2 had seven seats, the Crew Dragon interior shown last week had only five seats installed, although with room for at least one more.

Development of Dragon is on track for a series of test flights starting late next year, Hans Koenigsmann, vice president of mission assurance for SpaceX, said during a panel session on commercial crew at the AIAA Space 2015 conference in Pasadena, California, August 31. That includes an uncrewed test flight launching at the “end of ’16-ish,” he said, followed by an in-flight abort test in early 2017 and then a crewed demonstration mission to the station. Unlike Boeing, the crewed demo flight will carry two NASA astronauts, and no SpaceX personnel.

The demo launches, and later operational missions, will fly from the refurbished Launch Complex 39A at KSC, which SpaceX is leasing from NASA. That launch site, which will also be used for Falcon Heavy missions, will be operational by November, said Lee Rosen, SpaceX vice president for mission and launch operations, at a separate conference panel September 1. That includes completing a launch site readiness review that is one of the company’s CCtCap milestones.

SpaceX will also soon get its first order for a post-certification mission. “We’re in the process of ordering the first certification mission from SpaceX,” said Kathy Lueders, NASA’s commercial crew program manager, at the conference. She didn’t specify when that order would be formally announced.

The biggest near-term challenge for NASA and its CCtCap contractors is not necessarily technological but financial. With the start of the 2016 fiscal year less than three weeks away, there’s no resolution on any appropriations bills, including one that would fund NASA. House and Senate versions of those spending bills would given the commercial crew program $1 billion and $900 million, respectively, while the administration requested $1.243 billion (see “The commercial crew crunch”, The Space Review, June 15, 2015).

With no resolution in sight, the 2016 fiscal year will start under a short-term spending bill, called a continuing resolution (CR). That will allow programs to spend at the rate they were funded in 2015 for a few weeks, or maybe a few months, or possibly even longer, depending on how long it takes Congress to pass final spending bills for 2016.

That could be a problem for commercial crew, which was funded in 2015 at $805 million, two-thirds of its 2016 request. The administration has gone so far as to ask Congress to include a provision—known as an “anomaly”—to any CR it passes to allow the commercial crew program to spend at a higher rate.

“Without the anomaly,” stated an administration document to Congress listing request anomalies for any CR, “NASA would have insufficient funding for activities carried out by its commercial contractors during the CR period, forcing a work stoppage that would result in substantial delays that would lengthen U.S. dependence on other countries for crewed access to space.”

| “When we understand what the actual budget is, then we will be working with the partners to make sure that we then work to mitigate any impacts if there is a reduction in the budget,” Lueders said. |

And what if that final 2016 spending bill does fund the commercial crew program at some level below the administration’s request, such as the House’s $1 billion or Senate’s $900 million? The agency has left open the possibility of having to go back and renegotiate the contracts it has, potentially further delaying the program. NASA administrator Charles Bolden has publicly warned of that possibility in forums ranging from letters to Congress to an op-ed published last month by Wired.

“When we understand what the actual budget is, then we will be working with the partners to make sure that we then work to mitigate any impacts if there is a reduction in the budget,” Lueders said at AIAA Space 2015.

What those mitigations might be will depend on exactly what funding NASA ends up with, and when a final budget is passed, so for now there’s no specific plan in place. “It will depend on exactly what the budget is and how far we’re short,” said Phil McAlister, director of NASA’s commercial spaceflight development division, in a September 1 interview during the conference. “We’re just going to have to see how it plays out.”

The companies are also waiting to see how the budget debate plays out. “Obviously, if NASA didn’t get the budget level that is needed to fund the partners, it certainly could have an impact,” Boeing’s Mulholland said. “It’s hard for us to evaluate that.”

One legislator, though, was still confident about commercial crew’s funding prospects. “Of course, right now we’ve got a fight in Congress over the amount of money that will go into commercial crew,” Sen. Nelson said at the C3PF grand opening. “We’ll get the funding that it needs so that we can get our American astronauts flying on American vehicles.”