Orbiting first: a reasonable strategy for a sustainable Mars programby Casey Dreier and Jason Callahan

|

| It is our belief that a sustainable, executable, and affordable path to the human exploration of Mars includes an orbital mission at Mars as a critical step. |

The workshop, chaired by Professor Scott Hubbard of Stanford University and Professor Emeritus John Logsdon of George Washington University, brought together key leaders from NASA’s science, technology, and human spaceflight directorates, individuals from major industry partners, leading scientists, policymakers, and congressional staff. Workshop participants addressed the commonly cited technical, budgetary, policy, and scientific obstacles to the human exploration of Mars.

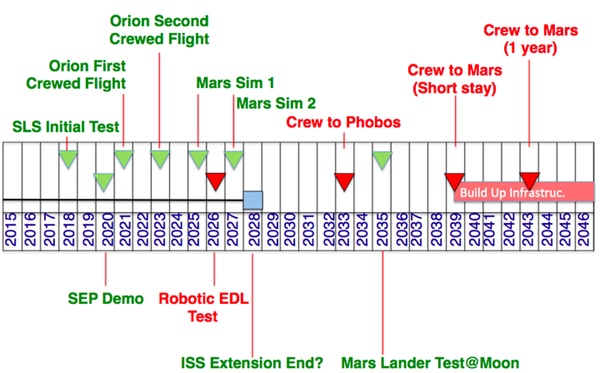

Workshop discussions (and the workshop report) examined a minimal Mars exploration architecture developed by a study group at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory as input to the current NASA planning process. The study team proposed a series of missions leading to a long-term human presence on the surface of Mars, as seen in Figure 1. These missions include hardware demonstration missions in cislunar space throughout the 2020s, a Mars orbit/Phobos mission in 2033, a human landing on the Moon in 2035 to validate landing hardware, and a short-stay surface mission on Mars by 2039. To the maximum extent practicable, the plan uses programs already in development or under study at NASA (such as the SLS, Orion, and solar electric propulsion transport vehicles), limiting new hardware development and thus minimizing a common source of budget overruns and schedule delays.

Figure 1. Notional Timeline for Mars Exploration Program. (Source: Hoppy Price, John Baker, and Firouz Naderi. “Humans to Mars: Thoughts Toward an Executable Program – Fitting Together Puzzle Pieces and Building Blocks.” Presented at the Humans Orbiting Mars Workshop, Washington, DC, March 31, 2015) |

It is our belief that a sustainable, executable, and affordable path to the human exploration of Mars includes an orbital mission at Mars as a critical step. The JPL study group’s plan demonstrates that an orbit-first approach to sending humans to Mars is both plausible and monetarily preferable. It also provides public benchmarks to demonstrate progress toward the goal.

An orbital mission, particularly one that lands on Phobos, also provides ample opportunities to advance our scientific understanding of Mars and its moons, tests our technological capabilities, and engages the public with an unprecedented adventure in space exploration. Humans would travel farther, stay longer, and assume more risk than at any other point in NASA’s history.

| The architecture presented by the JPL study team is not the only path forward, nor was it meant to be: it represents a “proof of concept” that NASA could engage in a sustainable human exploration program at Mars in a reasonable timeframe without a major increase in its budget. |

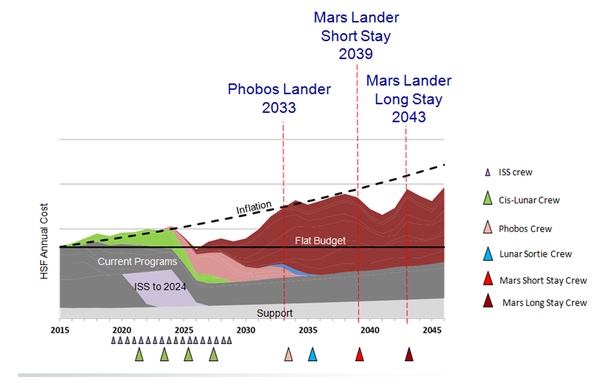

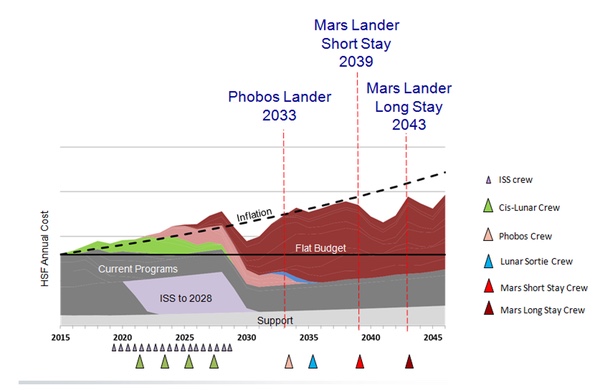

The JPL study team asked the Aerospace Corporation to subject its plan to the same cost analysis approach Aerospace had applied to the Mars exploration concepts in the National Academies’ 2014 report, Pathways to Exploration. Aerospace found that the JPL architecture could plausibly be implemented within a human spaceflight budget that grew only with inflation, as seen in Figure 2, provided that NASA withdraws from its lead role in funding operation of the International Space Station by the mid-to-late 2020s. The half-trillion dollar price tag for getting to Mars that was a product of the 1989 Space Exploration Initiative is clearly no longer relevant.

Figure 2. JPL Study Group’s Architecture Assuming ISS Extended to 2024 (top) and 2028. (Source: Terry Radcliff and Russell Persinger. “Humans to Mars: Thoughts Toward an Executable Program - Fitting Together Puzzle Pieces and Building Blocks.” Presented at the Humans Orbiting Mars Workshop, Washington, DC, March 31, 2015) |

The JPL study group’s plan once again demonstrates that the human spaceflight budget needs to grow, at minimum, with inflation. But just as importantly, it demonstrates that a mission within a reasonable time span is possible without politically unfeasible increases to NASA’s overall budget. No new “Kennedy moments” are needed.

All of this said, humans will not reach the Red Planet using the exact architecture discussed above. At this early stage, it is impossible for any plan to anticipate all the future technological, political, and engineering advances yet to come. But work can be done to define and articulate an executable strategy.

The architecture presented by the JPL study team is not the only path forward, nor was it meant to be: it represents a “proof of concept” that NASA could engage in a sustainable human exploration program at Mars in a reasonable timeframe without a major increase in its budget. The JPL study team has, however, suggested that an orbit-first strategy is a compelling solution to challenges in cost, sustainability, and building coalitions. The orbit-first idea is under study by several groups within NASA who are developing mission architectures to the Red Planet.

History has demonstrated the power of coalitions in maintaining decades-long human spaceflight programs. A sustainable strategy depends on a coalition of a broad range of relevant stakeholders, including scientists, technologists, other groups interested in exploring Mars, major industry invested in existing programs, new private sector space firms, international partners, political leaders, wide swaths of the public, and, of course, NASA itself. The Humans Orbiting Mars workshop intended to provide a starting point for engaging these groups in a discussion of how to approach a sustainable program of human exploration of Mars.

The Planetary Society’s preference of Mars as the destination for the US human spaceflight program is not simply a matter of opinion. It is the stated policy of Congress, the White House, and NASA. Articulating a specific strategy for achieving that goal will provide the focus around which this coalition of stakeholders in government, industry, science, Congress, and the public can emerge.

NASA will have the lead role in implementing a human exploration of Mars program architecture due to the comparative capabilities and resources available, but it will need partners in the enterprise. International partnerships are widely acknowledged as a necessity for any major undertaking in space.1 Other nations can contribute technical expertise and monetary support, and collaboration in space strengthens international relationships on Earth.

| The next step in establishing a coalition around a sustainable program of Mars exploration will center on better communication. |

However, without a clear strategy for reaching Mars, defining such partnerships will be difficult. Leaders of other nations’ space agencies need to understand NASA’s strategy in terms of schedule and resources to determine how they are able to contribute. The space agencies of other nations also require detailed information far in advance of executing the program so that they may begin the process of establishing the funding, staffing, and infrastructure requirements for their nation’s contribution. After all, the political process that dictates NASA’s budget can look downright streamlined when compared to the process many other space agencies must navigate.

In a similar vein, the private sector would benefit from a clear government strategy to assist in defining its potential role in the human exploration of Mars. NASA’s commercial partners will have personnel and infrastructure requirements to plan for and are highly capable in assisting NASA to identify and address the technical challenges at every stage of planning. And while NASA cannot lobby Congress on its own behalf, industry partners have no such restriction. Once NASA articulates its strategy for sending humans to Mars, industry leaders will be able to assess their companies’ potential roles and begin requesting political support for the program.

The space science community should constitute an important component of any coalition for the human exploration of the Red Planet. A large community of Mars scientists should serve as a cornerstone of support, but workshop participants emphasized that this support is not a given. Historically, science has often been treated as an afterthought in human exploration missions, and science budgets have sometimes competed with (and lost to) human missions. To build support within the scientific community, it is imperative that any plans for human exploration to Mars involve the scientific community and incorporate its goals during early stages of development. It is also important that programmatic costs are managed so as not to threaten science missions within NASA.

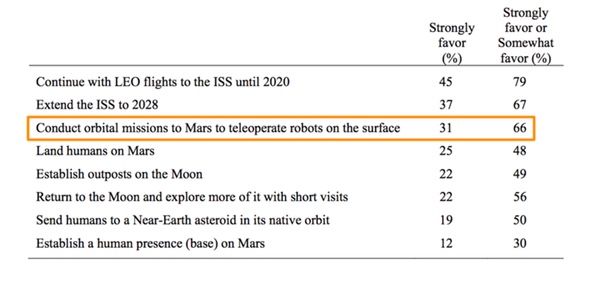

Finally, an intriguing example of how an orbit-first approach could serve to build a sustaining coalition around the future of human spaceflight comes from last year’s Pathways to Exploration report by the National Academies. They surveyed major stakeholders2 about the goals for NASA’s human spaceflight program over the next 20 years and found that, after extending operations of the ISS, an orbit mission to Mars garnered the highest levels support among this critical community, as seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Goals for NASA’s Human Spaceflight Program Over the Next 20 Years. (Source: Committee on Human Spaceflight, National Research Council. Pathways to Exploration: Rationales and Approaches for a U.S. Program of Human Space Exploration. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2014. Table 3.13) |

The next step in establishing a coalition around a sustainable program of Mars exploration will center on better communication. NASA and all of its potential partners need to understand the motivations and restrictions faced by each faction within the coalition. Factors affecting the decisions of each group are unlikely to remain static, so communication within the coalition will be a process, not a single activity.

The Planetary Society’s Humans Orbiting Mars workshop and report were intended to serve as a forum for communication among many of the likely partners in this coalition. The Society intends to continue working toward the goal of a sustainable Mars exploration program by reaching out to individuals and organizations interested in exploring Mars in an effort to keep the conversation going.

NASA has an opportunity to lead the world to Mars. But we must begin working to get there now.