Declassified documents offer a new perspective on Yuri Gagarin’s flightby Asif Siddiqi

|

| Despite all this quite impressive work, the principal challenge of doing Soviet space history has always been the problem of archival research. How do you go about digging into archives in Moscow to get at the documents, as one is able to do (for example) with the American space program? |

With Russian openness, a huge market opened up in the US and Europe for writers (mostly amateur historians or journalists) to step in and produce an unending stream of books on arcane aspects of the program. This strand has been further enriched by academics—mostly professional historians of modern Russia—who have looked at the rich cultural detritus of the Soviet space program. There’s a lot of this stuff out there, and some of it is very good, shedding light on the cultural importance of the Soviet space program as well as mapping how Russian culture has cultivate an interest in space exploration for well over a hundred years. (For those interested, I moderated a very interesting discussion on Soviet space culture a couple of years ago on the Russian History Blog.)

Gagarin being led to his spaceship at the top of the gantry by Oleg Ivanovsky who was the “lead” (production) designer of the Vostok spaceship. |

Despite all this quite impressive work, the principal challenge of doing Soviet space history has always been the problem of archival research. How do you go about digging into archives in Moscow to get at the documents, as one is able to do (for example) with the American space program? Since the early 1990s, it has actually been possible to visit archives in Moscow and get access to Party and government documents at various state archives. It’s not easy, but it can be done and there are many academics, both professors and graduate students, who routinely do research at Russian archives on a huge array of topics related to Soviet history. I myself have been in Moscow many times (including for months at a time) working at various archives for my book on the pre-Sputnik history of the Soviet space program.

Of course, as with any archival document, one has to have a critical eye and contextualize, evaluate, and weigh any document by drawing from other sources. Nevertheless, the availability of archival documents on the Soviet space program has been both a boon and source of confusion. Russian archival authorities, for example, published several collections of primary source documents in 2011 on the early days of the space program (all in Russian) which are now commercially available (I’ve written brief summaries of some of them in this NASA Newsletter, pp. 19–24) but at the same time, there is undoubtedly some selection bias in what has been included and what has been omitted. Selection bias is, of course, a problem with any published collection of archival documents but the Russian ones come with their own peculiar set of problems.

It was in this context that I was in Moscow this past summer and spent a month digging through archives on a non-space related book project (actually on the history of scientists and engineers who worked in the Stalinist Gulag). I had a few days left at the end and went digging for space-related documents. At the Russian State Archive of the Economy (RGAE), one can find thousands of fat binders containing records of the grim-sounding Military-Industrial Commission, the body that managed Soviet military R&D and production during much of the Cold War. These folders are heavy, dusty, and for the most part, no one has looked at them since they were originally put away by archivists. The richness of materials is quite astonishing. Over the past few years, I have found and collected an enormous amount of material on the space program and related fields. These include: plans and schedules for their interplanetary program; detailed lists of technical materials from the American aerospace industry coveted by Soviet industrial managers; documents complaining that secrecy at Baikonur (the site from where the Soviets launched their satellites and cosmonauts) was not strict enough; abandoned anti-satellite projects; and documents on their massive N-1 Moon program.

Ivanovsky helping Gagarin get settled in his ship. |

In this catalog of riches, in June of this year, I ran across a document on the historic flight of famed cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, who on April 12, 1961, became the first human being in space. The document sheds new light on that historical flight, revealing the enormous risks involved in that mission. Gagarin’s Vostok flight, of course, has been quite amply documented, in print and online (with quite a nice recent biography in English by Andrew Jenks). I myself published a lengthy account, based largely on official mission documents (released in 1991), in one my earlier books, Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945–1974. However, documents have continued to trickle out on the flight in the past decade, and while nothing that has been declassified fundamentally shifts our perception of the mission, the Russian declassifications from 2011 have clarified much about the flight. The document that I found also provides confirmation of certain aspects of the flight, which is all the more important given the proliferation of Gagarin conspiracy websites (especially in Russian) which are easy to find with a Google search. Many websites will tell you that Gagarin was not the first human in space, that there were earlier “lost cosmonauts,” and, most sensationally, that his untimely death in 1968 was part of some nefarious Communist Party plan.

| The document underscores what has often been overlooked by casual historians—that the flight of Gagarin’s Vostok was fundamentally embedded in a military environment. His spaceship was actually an offshoot variant of a new spy satellite (“Zenit”), not, as many often claim, that the spy satellite was the offshoot of the human variant. |

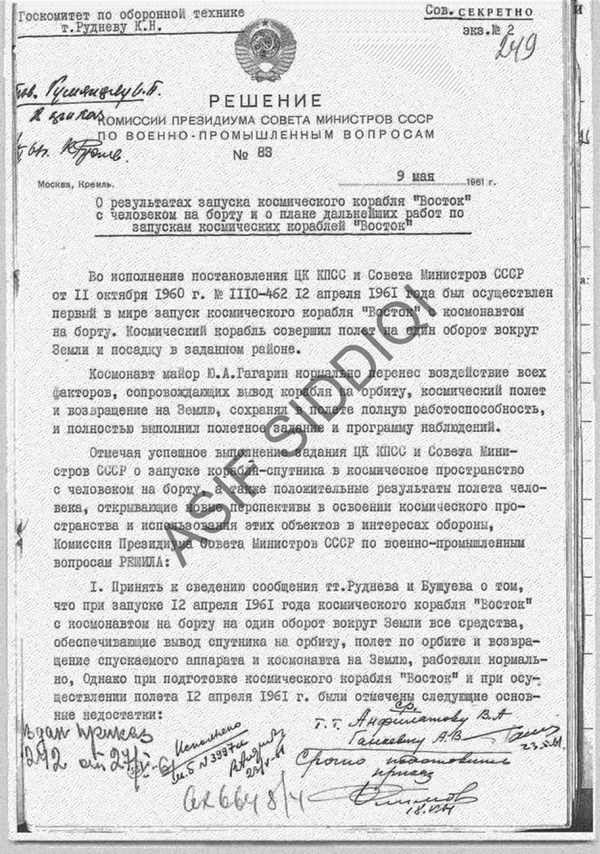

The text of my document was remarkably somber in tone, very much in line with Soviet bureaucratic norms. Its title a literal description of its contents: “On the Results of the Launch of the ‘Vostok’ Space Ship with a Human on Board and on Plans for Future Work on Launches of the ‘Vostok’ Space Ship.” What was this? It was the official summary report—classified “Top Secret”—on Gagarin’s mission prepared by designers for the highest levels of the Soviet government. This five-page summary report, produced on May 9, 1961, less than a month after Gagarin’s flight, briefly compiled all that engineers knew about the flight. How did Gagarin do? How well did his spaceship perform? What can we do next?

For a start, we can dismiss the notion that Gagarin was not well during the flight. The authors of the document note that “Cosmonaut Major Yu. A. Gagarin normally bore the effects of all the factors accompanying the insertion of [his] ship into orbit, the space flight, and the return to Earth, maintaining full working ability during the flight and fully completed the flight assignment and program of observation.”

The document underscores what has often been overlooked by casual historians—that the flight of Gagarin’s Vostok was fundamentally embedded in a military environment. His spaceship was actually an offshoot variant of a new spy satellite (“Zenit”), not, as many often claim, that the spy satellite was the offshoot of the human variant. Engineers basically took out the cameras from the spy satellite, added life support, an ejection seat, and redundancies, and rigged the spacecraft for a human being. Besides the document’s comment about a “program of observation,” we get an explicit confirmation of the military importance of Gagarin’s flight in the next sentence, when the authors note that the flight has “opened up new prospects in the mastery of cosmic space and the use of these objects for the interests of defense.”

The “USSR” insignia was not originally on Gagarin’s helmet but was painted on on the morning of his flight.

|

Despite the obvious note of self-congratulation about the flight (“all systems ensuring the insertion into orbit, flight in orbit, and return of the return module and the cosmonaut [back] to Earth, worked normally”) the document notes there were numerous “basic shortcomings” during the preparation and implementation of the mission. Going through these we get a rare and peculiar glimpse into the Cold War Soviet space program and its functioning in a climate of high stakes and incredibly high risk.

We find from the document that during the preparation of two precursor missions with dogs in March 1961, and then in manufacturing Gagarin’s actual vehicle, at least 70 anomalies were detected in instruments on the vehicle. Yet, still, the flight went ahead!

Second, the “air conditioning” (basically, the life support system on Vostok) “did not fully correspond to the [design] requirements,” meaning that life support was essentially operating at its limits for Gagarin.

| We also know that there were a few other “anomalies” (in NASA parlance) that marred the mission, including one that potentially could have killed Gagarin. |

Third, the “portable emergency reserve” (in Russian, known as NAZ for nosimyy avariynyy zapas), a package used by cosmonauts to survive (for about three extra days) in case of landing in an unexpected area, was insufficiently debugged, especially for emergency splashdowns, which was certainly a possibility. In fact, the document notes that after being ejected from his capsule after his single orbit, when Gagarin was parachuting down, “the cable connected to the [portable emergency reserve] snapped,” basically depriving him of these supplies. In other words, if he had actually landed way off target, he would have had to survive without any supplies.

Fourth, a key valve in an engine (known variously as the 8D719, RD-0109, or RO-7) on two upper stages was assembled incorrectly at the factory, which, the document notes, “could have led to a premature shutdown of the engine and [failure] of orbital insertion of the [spaceship].” One imagines the outcome for Gagarin if that had happened. The best case scenario was an unscheduled landing, perhaps in eastern Siberia, on the initial portion of the orbital ground track. The worst case, given all the unknowns, was a fatality. In fact, as I describe below, this particular valve and its operation during orbital insertion did put Gagarin’s life in serious jeopardy, but not in the way one might expect.

Fifth, the short-wave mode for the voice radio-communication system (known as “Zarya”) basically did not “provide for normal communications during flight of the cosmonaut with ground communication stations,” which explains the repeated complaints by both the ground and Gagarin of difficulty in hearing each other, not to mention the poor quality of the audio that has been released by Russian archivists.1 Yet, Gagarin recorded some vivid impressions of his time in orbit on a tape recorder in real time. (“The flight is proceeding marvelously. The feeling of weightlessness is no problem, I feel fine… At the edge of the Earth, at the edge of the horizon, there’s such a beautiful blue halo that becomes darker the farther it is from the Earth…”)

Sixth, one of the two onboard radar sensors (known as “Rubin”), which helped the ground track the coordinates of the spaceship, did not work during Gagarin’s flight. This meant that tracking data during the mission was spotty at best.

Finally, the spaceship’s main data recorder (a kind of “black box”) known as “Mir-V1” did not work during reentry and landing due to “unsound assembly” at the factory. This meant that much critical data on the final portion of Gagarin’s mission was simply never recorded, making troubleshooting after the mission that much harder.

Front page of the document found at an archive in Moscow reporting on the results of Gagarin's flight to government leaders. |

We also know that there were a few other “anomalies” (in NASA parlance) that marred the mission, including one that potentially could have killed Gagarin. During launch into orbit, the upper stage engine worked longer (the faulty valve!) than it should have, putting Gagarin in a much higher orbit than planned—the apogee of the orbit was 327 kilometers instead of 230 kilometers. This meant that in case the retrorocket system failed, Gagarin’s ship would not naturally decay after a week or so, or even after ten days—the absolute limit of resources in the ship. It would instead reenter after 30 days, by which time Gagarin would certainly be dead, having exhausted all the air inside. In other words, either the retrorocket worked, or Gagarin was a dead man.

| In his postflight report, he remembered, “I waited for separation. There was no separation.” |

During the actual flight, as soon as orbital insertion occurred, a timer known as Granit-5V activated. Precisely 67 minutes later, this timer sent a signal to fire the retrorocket engine (known as the S5.4) which, basically, did its job and deorbited Gagarin. In retrospect, that the retrorocket engine fired as it was intended to do is not terribly surprising given that it was one of the most ground-tested elements of the entire spaceship—17 out of 18 ground firings before the launch were successful. An interesting aside to all this is that during the entire time he was in space, Gagarin had no idea he was in the wrong orbit.

A much bigger problem occurred when, having ignited, the retrorocket engine stopped firing after 44 seconds, one second before the planned shutdown time due to another faulty valve. That one second meant that Gagarin would land 300 kilometers short of the planned target point. The lack of a proper shutdown also meant that some remaining propellant from the retro-engine (as well as residual gas from the gas bottles of the attitude control system) put Gagarin’s ship in an uncontrolled spin (of about 30° per second). Gagarin, as affable as always, reported on this in his later postflight report as a “corps de ballet” as the spaceship madly spun around. He remembered that it was “head, then feet, head, then feet, rotating rapidly. Everything was spinning around. Now I see Africa… next the horizon, then the sky… I was wondering what was going on.”

The problem, however, was much more serious than anyone could have anticipated, for the unexpected spin disrupted the internal program that would have immediately (four to eight seconds after engine shutdown) led to separation of the two modules that made up the Vostok spaceship: the spherical descent module carrying Gagarin, and the conical instrument module, which lacked a heat shield but ideally would burn up separately far from Gagarin’s capsule. In his postflight report, he remembered, “I waited for separation. There was no separation.” Instead, shackled to each other, the two objects began to enter the atmosphere as one. This was highly dangerous, for parts of the module not designed to survive reentry could have easily impacted and blown through Gagarin’s capsule. Fortunately for Gagarin, about ten minutes later, the two parts of Vostok separated, at an altitude of about 150–170 kilometers above the Mediterranean. That was lower than usual, but still high enough that Gagarin’s capsule was unharmed. And even then all was not safe. For a few seconds, a wiring harness kept the two modules connected, in a wild dance, separating only when four steel strips attaching the harness came off.

After experiencing about 10–12 g’s during reentry, Gagarin, once in the atmosphere, ejected from his capsule at an altitude of approximately seven kilometers. However, he soon discovered that once his primary large parachute deployed, the reserve parachute, slightly smaller than the primary one, also partially deployed. Fortunately, descending with one fully deployed parachute and one partial one—a recipe for disaster in a worst case scenario—did not adversely affect his descent. Gagarin was, however, busy with other problems: for six minutes, as he descended, he struggled to open a respiration valve on his spacesuit to help him breathe atmospheric air. His life was not in danger but it must have been extremely uncomfortable for a few tense minutes. Luckily, none the worse for the wear, he parachuted down safely at 1053 Moscow Time (not at 1055, as thought for decades).

| he many problems that Gagarin faced on his mission were not necessarily due to poor design or bad engineering, I would argue, but instead a combination of haste and poor workmanship on the factory floor. I would argue that the Vostok design was in fact excellent engineering if we define “excellent engineering” as also being incredibly robust. |

What does this all mean? Gagarin was an incredibly lucky man to have come out of this unhurt and alive. In rushing to accomplish a human spaceflight in the race with the US, Soviet engineers pushed the boundary of acceptable risk to its limits. Fortunately for Soviet planners everything went well. Sure, some of this was due to luck. Things that could have gone wrong didn’t. But some of it was also the undeniably robust design of the Vostok spaceship itself. Its relatively simple and elegant design was intended first and foremost to get a person into orbit and back as quickly and reliably as possible. The Soviets, for example, bypassed a slightly more complex blunt, truncated cone design (such as used on NASA’s Mercury spacecraft) in favor of a simple sphere capable of ballistic reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere.

The many problems that Gagarin faced on his mission were not necessarily due to poor design or bad engineering, I would argue, but instead a combination of haste and poor workmanship on the factory floor. Consider that the Vostok spacecraft consisted of 241 vacuum tubes, more than 6,000 transistors, 56 electric motors, and about 800 relays and switches connected by about 15 kilometers of cable. In addition, there were 880 plug connectors, each (on average) having 850 contact points. A total of 123 organizations, including 36 factories, contributed parts to the entire Vostok system. Despite redundancy in a large number of systems, human-rating such a spacecraft with absolute confidence was practically impossible. Yet, the way that Soviet engineers designed the system, it was meant to operate even at the blurry edges where parameters were pushed to the max. It is because of this that I would argue that the Vostok design was in fact excellent engineering if we define “excellent engineering” as also being incredibly robust.

The problem with Vostok was not the design itself but that it was insufficiently tested. There were too many bugs in the system that could have been eliminated in a slower testing program. But the frantic pace of the “space race” ensured that you had to sacrifice thorough ground testing in favor of debugging the technology in space. This means that you automatically increase the risk to human subjects on board spaceships. Extended ground testing versus flight testing is a tough call for mission managers, and depending on the urgency (as in Apollo 8, for example), you sometimes do something on the mission that you haven’t really tested on the ground—or can’t test at all.

What all this tells us is that while “good engineering” has some objective measures for evaluation, we also need to introduce context into the equation. The question is not simply, “Will it get the job done?” The question is, “Will it get the job done, on time, and even if lots of things go wrong?” And in Gagarin’s case, the answer was obviously “yes.” Regardless of all the troubles on his mission, he will always be the first human being in space. You can’t take that away.