Review: Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Ageby Jeff Foust

|

| The exhibit is advertised by the museum as the “most significant collection of Russian spacecraft and artifacts ever to be shown in the UK.” In fact, it may be the most significant collection ever shown outside of Russia. |

Russian and Soviet-era human spaceflight hardware, by contrast, is harder to find. A few Soyuz capsules have made their way to the West, including some bought by the space tourists who flew back from the ISS in them. However, there’s still a lot of space history treasures that remain largely out of view, which makes a new exhibit at London’s Science Museum so intriguing.

“Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age” is advertised by the museum as the “most significant collection of Russian spacecraft and artifacts ever to be shown in the UK.” In fact, it may be the most significant collection ever shown outside of Russia, including some rare items never before placed on public display from the early history of the Soviet human spaceflight program.

The Vostok 6 descent capsule, flown by Valentina Tereshkova. (credit: J. Foust) |

The centerpiece of the display is, ironically, a piece of hardware that never flew in space: an engineering model of the LK-3, the Soviet equivalent of NASA’s Lunar Module. The lander, five meters tall, was designed to accommodate a single cosmonaut to land on the Moon and lift off again. The level of detail visible, like cabling running along the vehicle’s exterior, makes it clear that this is not a model or low-fidelity mockup, but something close to actual flight hardware—hardware, though, that never flew as the Soviet Moon program stalled and was eventually cancelled.

There is also space-flown hardware in the exhibit. Sitting next to each other are the capsules for Vostok 6, flown by the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova; and Voskhod 1, the first mission to carry three people in space. Sitting next to each other demonstrates that Voskhod 1 was no bigger than Vostok 6, yet crammed seats for three people inside. Elsewhere in the exhibit is Soyuz TM-14 capsule from a mission to Mir in the early 1990s.

Memorabilia from the early Soviet space program, including a lab coat with “SPACE IS OURS!” hand-written on it by an enthusiastic Russian medical student. (credit: J. Foust) |

There are a lot of other, smaller items in the exhibition as well: models of early Sputnik satellites and a Lunokhod rover, spacesuits (including one worn by the first Briton in space, Helen Sharman) and other garments, and a variety of other items about the cultural significance of spaceflight. One example of the latter is a Russian medical student’s white lab coat, with the Russian phrase “SPACE IS OURS!” hand-written in red paint on it, an example of the improvised celebrations of the Russian people after Yuri Gagarin’s historic flight in 1961.

| Is this final room a memorial to Gagarin, or to a space program that once led the world but is now, in many respects, only a shadow of its former self? |

These artifacts, big and small, certainty constitute one of the most significant collections of Russian/Soviet space history ever displayed outside of Russia. But what message does the exhibition tell? That’s harder to say. It’s not a comprehensive history of Russian human spaceflight, since it skips around, going from the early flights of Gagarin and Tereshkova to the failed lunar landing effort, then jumping all the way to the Mir and International Space Station eras. It’s a taste of the past and present of Russian spaceflight and its cultural impact.

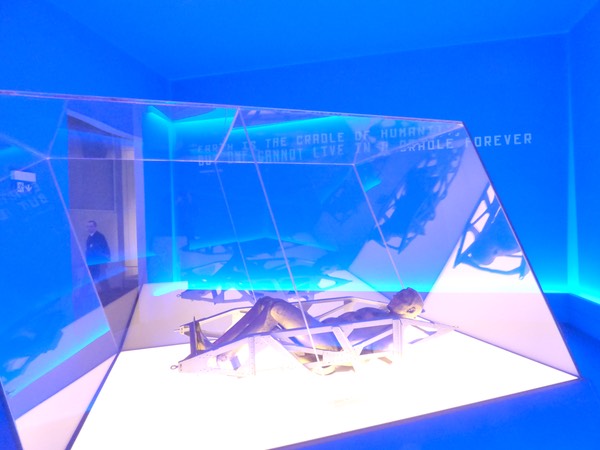

The exhibition ends on something of an odd note. After going through a room with exhibits from the Mir and ISS era, the final room before exiting (into the gift shop, of course) contains only a single item: a “tissue-equivalent mannequin” flown around the Moon on the Zond 7 mission to measure radiation levels. Its face is modeled after Gagarin. It lies in a glass case in the middle of the room, which is bathed in eerie blue lights, and with Tsiolkovsky’s famous quote about the Earth being the cradle of humanity is on the otherwise bare walls. Is this a memorial to Gagarin, or to a space program that once led the world but is now, in many respects, only a shadow of its former self?

The final room of the exhibit, containing only a “tissue-equivalent mannequin” with Gagarin’s face that was flown around the Moon. (credit: J. Foust) |

While it may not be a complete history of Russian human spaceflight, “Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age” is still an interesting exhibition in large part because of the rare displays of hardware, like the lunar lander prototype and the Vostok and Voskhod capsules; it’s worth a visit if you’re in London in the next few months.