The wizard war in orbit (part 4)P-11, FARRAH, RAQUEL, DRACULA, and KAL-007<< page 1: the P-11 follow-on and the ABM radar hunt Stanford Electronics Laboratory and the Vietnam War comes to SIGINTIn May 1967, the magazine Missiles and Rockets published an artist’s illustration of a small experimental satellite with a mass of 122 kilograms (270 pounds) reportedly scheduled for launch later in the year. The satellite was clearly derived from the brick-shaped P-11, and according to the photo caption it was intended to measure radiation in orbit. Space World magazine published the same photograph on its cover in September 1967 with the caption: “Artist’s concept shows satellite built by Lockheed Missiles & Space Co. for the Air Force. Craft will carry aloft two types of reflective optical surfaces for exposure to space environment. Also, instruments aboard will measure radiation and other space phenomena.” In the artist’s illustration the small solid propellant kick motor was visible at the top. But despite its unclassified nature and apparent scientific mission, no known scientific publications resulted from this mission, and no independent observer ever connected it to the secretive subsatellite program. The RAE Table of Earth Satellites listed a subsatellite deployed from a KH-4B CORONA reconnaissance satellite in November 1967 as “Module 283,” which may have been this satellite. Another P-11 variant appeared in the National Museum of the United States Air Force where it hung from the ceiling until at least the mid-1990s. It was labeled as “Lockheed Research Satellite” and sprouted numerous antennas that made it look like it was clearly intended to intercept many different radio signals. Apparently, in the early 1990s Lockheed also produced a small brochure touting a similar satellite that could be deployed off a converted surplus submarine ballistic missile launched from land.

Whereas the satellites were constructed by Lockheed, the payloads were built by other organizations. The Stanford Electronics Laboratory had played a key role in developing prototype AFTRACK payloads and apparently the lab also began working on payloads for the P-11 satellites when they were in development. According to James de Broekert in an oral history produced by the National Reconnaissance Office, “Of all the payloads we built at Stanford, all but one of them worked perfectly to the end of the vehicle life. One vehicle blew up on launch and went into the water. Consequently, we were generally pleased with the reliability of our systems.” Brockert’s allusion to a lost satellite is almost certainly reference to the first launch in March 1963. By the late 1960s, anti-war protests were raging across American universities. At Stanford, south of San Francisco, it was common to hear glass shatter in the night as students hurled bricks through the windows of buildings that they thought—not always accurately—were involved in war research. By the spring of 1969, students had already burned down one Stanford building where future military officers were trained, and disrupted CIA recruiting on campus. But although the situation was tense, it was still relatively peaceful. Stanford conducted a lot of aeronautics research, and the aeronautics department was naturally a target. Professors and graduate students regularly stood guard in the offices overnight, protecting their notes and equipment. But the protestors soon turned their attention to the Stanford Applied Electronics Laboratory, which they knew conducted classified research. De Broekert, who had worked at the laboratory since the late 1950s, had stood overnight guard in his lab protecting the safe and its classified contents. In April 1969 the protests came to a peak and de Broekert vividly remembered what happened. “The student radicals, together with their outside professional advisors, took over the classified research laboratory by force and held it as ‘liberated territory’ for nine days,” he recalled, three decades later. “They put posters printed in Moscow and China on the walls, including Che Guevara posters.” Fortunately for de Broekert and his sponsor, the National Reconnaissance Office, the students never got into the safe or exposed his research. If they had, it would have been a serious blow to national security, equivalent or greater to the damage that a Soviet spy could accomplish. The NRO quickly moved the contents of de Broekert’s safe to a more secure location. But soon after the April occupation of the lab, the protests at Stanford became more violent. Only a few months later the sounds of breaking glass were replaced by the sounds of exploding tear-gas canisters as police sought to quell the student protests. Students set fire to the university president’s office, and in October 1969 the president of the university capitulated to the students, closed the lab, and fired all of its faculty, staff, and graduate students. De Broekert and his classified research had to move somewhere else. Their job was too important to abandon.

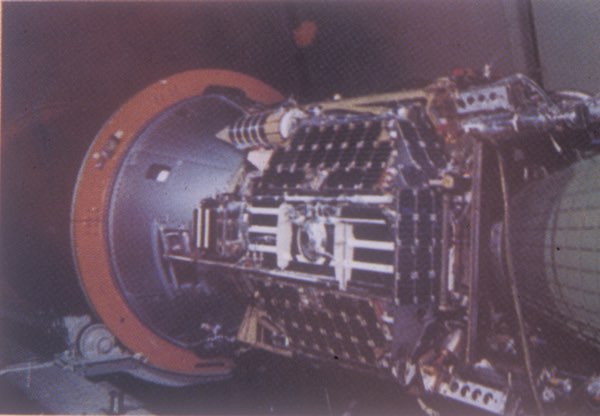

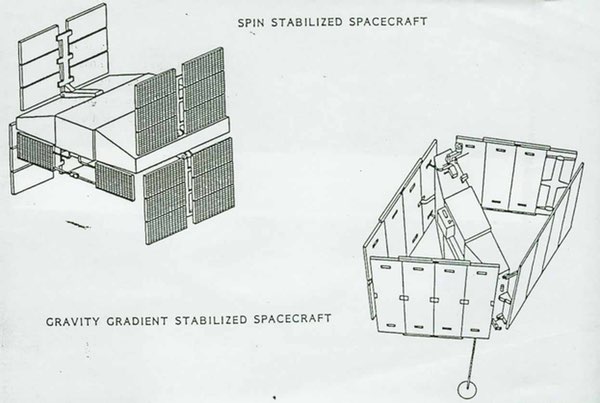

URSULA, RAQUEL, FARRAH… and DRACULABy the late 1960s the US Naval Research Lab (NRL), which had built the POPPY satellites, was increasingly interested in using its SIGINT satellites to detect vessels at sea. POPPY had long served in a general search role, detecting new and unusual signals, but now it was being redirected towards finding Soviet naval vessels, a subject of much interest to the NRL’s patrons in the US Navy. As a result, the SIGINT subsatellites undoubtedly took on some more general search duties from POPPY. The subsatellites had by the early 1970s adopted names such as URSULA, RAQUEL, and FARRAH, although whether these applied to classes of satellites or simply individual satellites is unclear. Like the earlier Agena-based MULTIGROUP and STRAWMAN satellites, the individual payloads on these satellites were also given their own designations. These included TIVOLI, TRIPOS, SOUSEA, and LAMPAN. For example, TRIPOS IV-SOUSEA II, a pair of payloads apparently launched aboard a subsatellite in the early 1970s, were intended for “general search” in the 4,000–12,000 megahertz range, whereas TIVOLI-II and TIVOLI-III were designed for technical intelligence collection in the 50–4,020 megahertz range. TIVOLI-II was delivered in spring 1969, although it is unclear when it was eventually launched. TOPHAT-I was a communications intelligence payload for intercepting signals in the 450–1,000 megahertz range. VAMPAN-II was another general search payload in the 100–1,000 megahertz range. LAMPAN-III and SAMPAN-IV operated in the 1,000–4,000 megahertz range. TRISOV-I was a technical intelligence payload in the 4,000–12,000 megahertz range. ARROYO-I was a communications intelligence payload scanning the 1,200–2,250 megahertz range. In a recently-published book of recollections of the NRO’s West Coast spacecraft operations, Don Thursby recounted that one of the SIGINT subsatellites was developed for tactical uses. “Back in the early 1970’s the new mission was to get data directly to the commander on the FEBA (Forward Edge of the Battle Area). I had a payload with possibilities if it could be ‘trailerized.’ We decided to go for it but needed a catchy name, so we used DRACULA… Direct Readout and Collection ULA (‘ULA’ was the three-letter shorthand for the URSULA payload). I put a briefing together to take east, but needed to get it through SP-1 [the head office]. General Bradburn liked the briefing but trashed the name, saying that he could already hear the welcome by the East Coast: ‘Oh, no, not another blood sucking program from out west!’” Thursby also recounted, “Later, at 450 pounds [205 kilograms], the subsats rode sidesaddle on HEXAGON into orbit.” Thursby may have been referring to the three Boeing Small Secondary Satellites launched off of HEXAGON spacecraft in 1974, 1975, and 1976. Some information on those unclassified satellites, including photographs, has long been public.

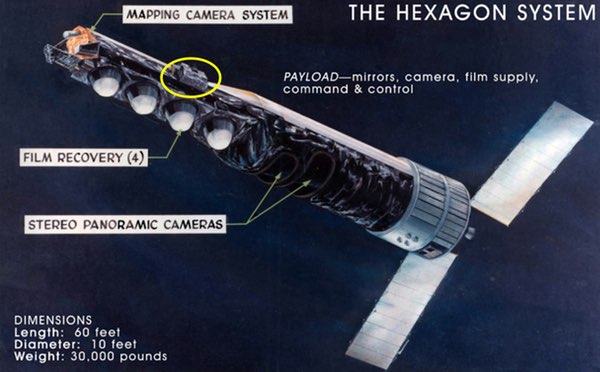

Thursby’s comment is curious, because it implies that all the HEXAGON-launched subsatellites were this larger size. But there is no other evidence that Boeing took over the role of building the SIGINT subsatellites after Lockheed had performed the mission since 1962. Exactly when and how the subsatellites evolved remains unclear from available evidence. HEXAGONs were capable of launching more than one subsatellite at a time. On several occasions the HEXAGONs carried a Boeing scientific satellite and a signals intelligence satellite, or two of the small SIGINT satellites heading to different orbits. An artist impression of HEXAGON, declassified in 2011, reveals one of these satellites mounted to the HEXAGON’s forebody. KAL-007In September 1983, a Soviet fighter jet shot down Korean Air Lines flight 007, a civilian 747 passenger jet. All 269 passengers and crew were killed. The Soviet air defense establishment believed that the plane was a US Air Force RC-135 Rivet Joint signals intelligence aircraft collecting information on their air defenses, but shot it down after it had already overflown Soviet territory and was over the Sea of Japan. As was typical of the era, the Soviet public response was poorly coordinated and filled with inaccuracies. A few days after the incident the Soviet government released a map allegedly showing the ground track of the Korean airliner along with American intelligence aircraft and spacecraft in the vicinity. The Soviets identified an American satellite as “Ferret-D” and showed its flight path near that of the airliner, supposedly in an American effort to coordinate operations—using the satellite to collect Soviet radar signals as the radars tracked the airliner in Soviet airspace. The Soviet claim was similar to the concept in the 1966 CIA proposal for a provocative flight by an A-11 OXCART. But the satellite was following an impossible flight path in the Soviet map. It was traveling to the southeast rather than the southwest (i.e. matching the direction of the Earth’s rotation), and it changed direction during its flight, which satellites cannot do. British independent satellite observer Anthony Kenden identified the satellite as 1982-41C, which had been launched in May 1982 off the back of a HEXAGON high-resolution reconnaissance satellite. As Kenden noted, however, the Soviet ground track for the satellite was also far from the actual ground track of the satellite by up to 800 kilometers. Later, space historian James Oberg noted that the satellite was also in entirely the wrong position to intercept the radar signals—assuming the radars were pointed at the airliner, the satellite was behind the radars, not a good location for intercepting signals heading in the other direction. The last known subsatellite was launched in 1984 from a HEXAGON reconnaissance satellite. At least three subsatellites, as well as the three Boeing science satellites, were deployed from HEXAGON spacecraft during the HEXAGON’s operational lifetime of 1971 to 1984. A failed HEXAGON launch in 1986 also probably carried one of these satellites.

The end of the lineOn September 5, 1988, the US Air Force launched a classified payload atop a Titan II rocket from Vandenberg Air Force Base. It deployed a satellite into an 85-degree, 500-nautical-mile (925-kilometer) circular orbit. Ground observers noticed that the satellite spun at approximately the same rate as the subsatellites deployed by the KH-9 satellites. A second launch took place exactly one year later on September 5, 1989. This satellite apparently suffered some kind of failure, however, and broke into several pieces. A third launch took place on April 25, 1992. It is likely that these Titan II satellites were the direct linear descendent of the earlier SIGINT satellites that started with the P-11s. With the retirement of the large HEXAGON reconnaissance satellite in the mid-1980s, the NRO had to find another means of placing its small SIGINT satellites in orbit. The Titan II Space Launch Vehicle, constructed from refurbished decommissioned ICBMs, was the answer. At the time, the small Scout rocket was the only other American launch vehicle in the payload class as the subsatellites, but the few remaining Scouts had been allocated to other missions.

The Titan II was capable of placing a 4,200-pound (1,90-kilogram) payload into a 90-degree, 100-nautical-mile (185-kilometer) circular orbit, more than enough performance to lift a relatively small satellite to a higher orbit where its own kick stage could take over. The SIGINT satellites were placed in 500-nautical-mile orbits. According to a list of mission numbers obtained by the author, these satellites were given mission designations of 5103, 5104, and 5105. In the early 1990s, an unclassified report indicated that the NRO was consolidating two low Earth orbit intelligence systems. These were most likely the descendants of the P-11 subsatellites and the Navy’s SIGINT program that for many years had primarily focused on finding ships at sea. Several remaining Titan II launch vehicles, that had possibly been allocated to launching remaining SIGINT subsatellites were no longer required and were made available to other users. One of those rockets was later used to launch the Clementine mission for the Strategic Defense Initiative Office. According to one source, satellites launched in 1982 and 1984 were not turned off until 2004. If accurate, it could explain why the program has not been declassified. In general, the National Reconnaissance Office appears to follow a policy whereby it does not declassify programs until at least 25 years after the last satellite in the program has ceased operating. If the satellites launched in 1988 and 1992 each lasted two decades like some of their predecessors, they may not have ceased operating until relatively recently. Thus, this program would not be evaluated for declassification until the 2030s. ConclusionAssessing the missions and the effectiveness of these numerous small SIGINT satellites over their four decades of operation is difficult. But compared to only a couple of years ago, a substantial amount of information on early American signals intelligence operations has now been declassified, such as the STRAWMAN and MULTIGROUP programs, and the almost completely unknown AFTRACK program. This new information has provided a detailed—if still somewhat confusing—picture of just how complex and diverse the early years of American satellite signals intelligence was. These low-altitude satellites, with few exceptions, began to give way to fewer, larger SIGINT satellites located in geosynchronous orbit and capable of performing a multitude of missions. The history of those later programs is likely to remain shrouded in mystery for many years to come. But the early war of the wizards, chasing invisible signals in air and space, is finally starting to come into focus. About this series: The information in this series has been derived from numerous sources, but the primary sources are the different versions of The SIGINT Satellite Story declassified in 2015 and 2016, the AFTRACK document declassification, and documents obtained by the author over several decades from the National Archives and other collections, as well as other sources mentioned in the text. New SIGINT documents are due to be declassified possibly within the next month, undoubtedly adding greater detail and context to this complicated story. Home |

|