A taste of Armageddon (part 2)by Charles Vick and Dwayne Day

|

| It was clear that something—something big—a rocket the size of a Saturn V, which the CIA called the “J vehicle”, had exploded there, very near the ground. |

Rooney picked up a roll of positive film from the latest CORONA reconnaissance mission to fly over the Soviet Union, Mission 1107, a KH-4B version of the venerable spy satellite that had returned its film to Earth only a few days before. Unlike a negative, a positive looks like the object that is photographed, and when light is shown through it the film reveals a high-quality image, much better than a paper print. Rooney loaded up the film at his light table and scrolled to a section of the vast Soviet Tyuratam launch range.

“Jesus Christ!” Rooney shouted.

His exclamation caused heads to jerk up throughout the room, like prairie dogs popping out of their holes at the sound of a squeak. There on the film was a vast smudge at one of the two Complex J launch pads for launching the giant Soviet Moon rocket. It was clear that something—something big—a rocket the size of a Saturn V, which the CIA called the “J vehicle”, had exploded there, very near the ground.

The devastation was immense. But the US intelligence community had been expecting something like that.

On June 11, an American GAMBIT-3 reconnaissance satellite flew over Tyuratam and photographed one of the big J vehicles on the launch pad. A declassified image taken from a CIA report gives some indication of the clarity of the photo and the details it showed. The original film, which sits in a classified cold storage vault today, undoubtedly reveals even more detail. What photo-interpreters were easily able to discern when they looked at the photos, probably in late June, was that this was not a flight vehicle. Previous flight vehicles spotted on the launch pads had launch escape towers on top; this rocket did not.

The timing of the photograph was actually bad luck on the part of the US intelligence community—it was too early. Just a few days later, the Soviets rolled out the flight vehicle “5L” from the large MIK assembly building to the pad in preparation for launch on July 3, 1969. It was a spectacular sight—two rockets, nearly the size of the American Saturn V, both on their launch pads. The Soviets took numerous photographs of the two rockets from a helicopter and the ground. But after conducting some checks, the Soviets lowered the non-flight vehicle onto its transporter and took it back to the massive building on June 22, 1969, leaving the “5L” vehicle on the pad ready for launch.

By late June 1969, the US intelligence community started to collect data indicating that another major launch was scheduled from Baikonur, which they then referred to as the Tyuratam launch range. On June 27, a National Security Agency report stated that “Soviet space support ship movements [approximately 2–5 words of text deleted] activity in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans suggest that preparations are again underway for a probably unmanned circumlunar mission from Tyuratam during the first week of July.” The report stated that the Soviet tracking ship Komarov “is scheduled to arrive at its circumlunar support station off Havana within the next few days.” Other ships in the South Atlantic were near or approaching their stations, and two more were en route to the Indian Ocean and would be on station by the first week of July. Furthermore, “The Soviet Space Vehicle Recovery Ships (SSVRS) in the Indian Ocean probably have begun their operational deployment in support of a forthcoming mission.” Several deleted lines of text in the declassified document probably referred to previous times the NSA had observed Soviet space tracking ships behaving in certain ways indicating “a major space operation of this type.”

| In fact, the Soviets had attempted to launch their giant N-1 rocket on the evening of July 3. It rose above the pad only a few hundred meters, suffered a major engine failure, settled down onto the pad, and blew itself to smithereens. |

What the US intelligence community was expecting was another Zond circumlunar mission. Apollo 8 had orbited the Moon in December 1968, followed by Apollo 9 and then the Apollo 10 lunar landing dress rehearsal in May. The United States had assumed a commanding lead in the Moon race. But there were no indications that the Soviet Union had given up on trying to send cosmonauts around the Moon or to land there. In mid-June, the Soviets had launched a Proton rocket from Tyuratam that failed. That time the Soviets had not deployed any recovery forces like they would if a spacecraft was going to come down in the ocean. The US intelligence community did not know what the mission was, but it was the first of a series of robotic lunar sample return missions. Now in late June, Soviet activities looked similar to previous Zond attempts, with recovery forces deploying in addition to the tracking ships. NASA was planning on launching Apollo 11 on a lunar landing mission later in July. The Soviets knew this, and American intelligence analysts knew this. Certainly NASA and American intelligence analysts would have been attuned to any Soviet effort to upstage Apollo 11.

Soon the NSA analysts reported that, on July 1, the support ships Bezhitsa and Morzhovets had moved into positions that appeared “most compatible to support a translunar injection 5/6 July.” A few days later, the National Security Agency’s Defense Special Missile and Astronautics Center (DEF/SMAC) Watch Center produced a cable designated “Top Secret UMBRA”—the last code-word referred to communications intelligence. In addition to tracking ship movements, the cable stated “Comments following the Zond 5/6 circumlunar flights in late 1968, the Soviets have met with no success in further attempts to prove the techniques of this mission profile. A launch on 20 January failed early in flight, and a mission in February, probably planned for around the 22nd, was canceled prior to any actual launch attempt.” The Soviets had indeed launched on February 19, but they had launched a Lunokhod rover, not a Zond spacecraft; it had failed. The US intelligence community did not detect that launch, or the first launch of the giant N-1 rocket, which took place on February 21 and was also unsuccessful (see “A taste of Armageddon (part 1)”, The Space Review, January 3, 2017)

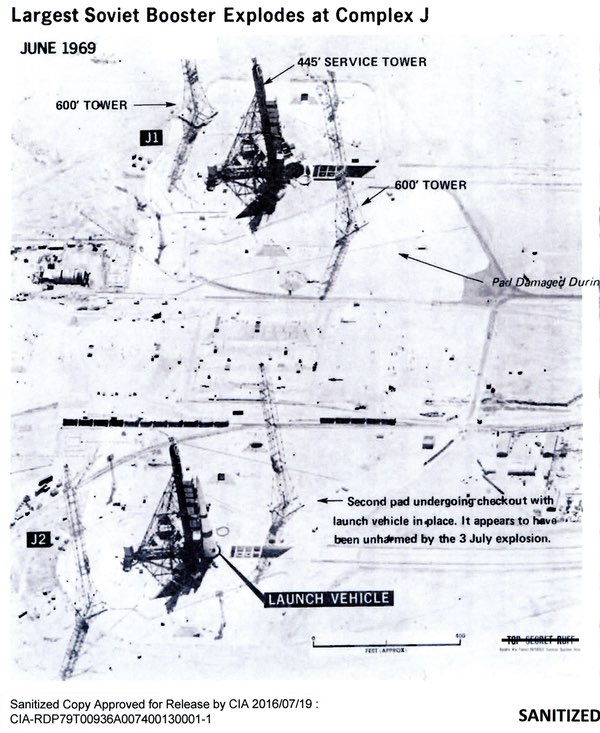

Image taken from a declassified intelligence report showing the non-flight N-1 rocket on the launch pad in June 1969. The annotations were produced by the CIA and a photo of the damaged pad was included for contrast. |

On July 3, the NSA produced another cable. The cable stated that the Tyuratam range head had been activated for a launch and the space tracking ships had been deployed to their operating locations to track a launch, but there was no indication of a launch. The ships had not received any future orders to stand by awaiting a launch. “Although the possibility exists that the mission suffered a very early in-flight failure, there were no strong reflections to support this.”

In fact, the Soviets had attempted to launch their giant N-1 rocket on the evening of July 3. It rose above the pad only a few hundred meters, suffered a major engine failure, settled down onto the pad, and blew itself to smithereens. Many Soviet officials, including cosmonauts, were there and watched the giant explosion. The next day, many of them were at the American embassy for an Independence Day party. None of them let slip that only a few hours earlier they had just watched one of the largest non-nuclear explosions to ever occur.

According to Dino Brugioni, who was then a senior official at NPIC, whenever the American ambassador to the Soviet Union was in the United States on business, the CIA would brief him on things to listen for in his meetings with Soviet officials in Moscow. The explosion at Tyuratam was the kind of thing the ambassador was supposed to listen for. Brugioni said that the ambassador never reported anything unusual from the party guests.

| Although they had no photographs of the destruction or other direct evidence of which rocket had blown up, the US intelligence community strongly suspected that it was the massive J-vehicle. |

But Brugioni also said that the United States had direct evidence of a big explosion at Tyuratam. He remembered that there was an “acoustic event” that had been detected by seismic sensors ringing the Soviet Union that indicated some kind of large explosion had taken place at Tyuratam on July 3. In addition, Brugioni also told Charles Vick in an interview that the explosion had shown up in a US military weather satellite image. To date, no documents have been declassified about either acoustic detection or the weather satellite image.

Although the NSA initially reported that there were no indications of a launch failure, DEF/SMAC’s analysts soon started to suspect that a rocket had blown up. DEF/SMAC quickly produced another cable reporting on “probable early in-flight failure of Soviet lunar mission.” This was based upon the departure of the Soviet space tracking ships from their operating locations. That implied that the rocket had blown up, although the NSA analysts also noted “it is also possible that a pre-launch malfunction could have caused the operation to have been aborted late in the countdown. Identification of the launch vehicle is uncertain.”

On July 5, the NSA produced another report stating that the launch had either been canceled or blown up early in flight. “Positive identification of the launch system cannot be made; however, this activity possibly involved the SL-12 multi-stage launch configuration.” The document implied that the Soviets used a coded signal sent to the tracking ships, probably over an unencrypted shortwave radio link that was a “possible operation termination message.” The vessels Bezhitsa and Morzhovets left their stations, which provided further evidence that the operation had been terminated. It also added that “activity is similar to that noted for previous cancellations/failures.”

But data was quickly accumulating at US intelligence centers. The big explosion was such an event that officials at Tyuratam had to report it back to their superiors. According to a 2007 interview that Charles Vick conducted with Melvin Laird, who had been Secretary of Defense in 1969, the US intelligence community intercepted some of these communications reporting about an explosion. This claim is supported by a declassified Central Intelligence Bulletin produced on August 15 titled “Largest Soviet Booster Explodes at Complex J.” The report states that “The explosion probably occurred on 3 July. On that day intercepted communications [several deleted words of text] disclosed that a booster had failed early in flight or on the pad. [several deleted words of text] strongly suggested that there had been an explosion of a vehicle [3–4 deleted words of text probably referring to the Proton rocket] the largest booster previously used by the Soviets.”

One declassified DEF/SMAC cable about the launch effort was mostly deleted, but included the cryptic statement “[deleted] for this operation, possibly suggesting that a different launch vehicle or flight profile was involved,” thus indicating that NSA analysts were also thinking it might not have been a Proton rocket like those used in previous Zond circumlunar attempts.

What the Central Intelligence Bulletin and the DEF/SMAC cable indicate is that although they had no photographs of the destruction or other direct evidence of which rocket had blown up, the US intelligence community strongly suspected that it was the massive J-vehicle and not a Proton (SL-12) rocket like the previous rocket failures in the Soviet Moon program.

On July 5, 1969, only 15 days before Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the Moon, intelligence officials delivered a President’s Daily Brief to President Richard Nixon that provided dramatic information on the status of the Moon Race.

A major Soviet unmanned space launch toward the Moon 3 July ended in failure as a result of an explosion on the launch pad or an early inflight failure of the launch vehicle.

Deployment of Soviet recovery ships in the Indian Ocean indicated that the spacecraft was intended to return to earth. [several deleted words in text] claimed that the USSR would launch a rocket to the Moon and bring back samples of lunar soil before the scheduled launch of the Apollo 11 mission. Whether this operation was intended to land on the Moon and bring back samples cannot be established at this time, but it is within Soviet technical capabilities to attempt such a mission.

The language in that PDB reflects the fact that at that time the CIA did not know exactly what kind of rocket had failed. Usually when the tracking and recovery ships deployed in that way a Zond spacecraft atop a Proton rocket was launched out of Tyuratam. At that time, that was the most likely culprit for the failure, until the communications intercept provided more information pointing toward the larger J-vehicle.

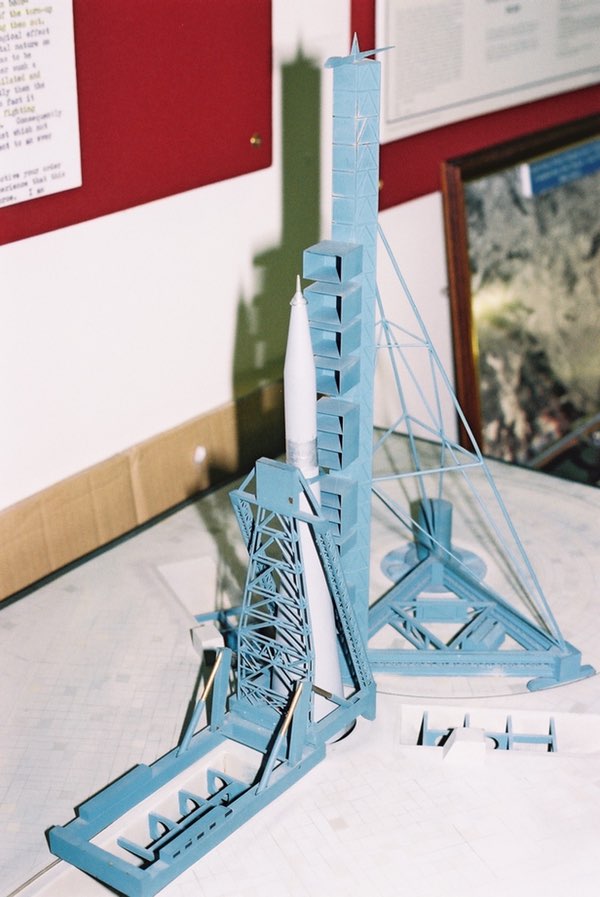

This model was made by CIA model-makers to show the large rocket that the CIA referred to as the “J-vehicle.” |

In later July, Apollo 11 launched to the Moon and Neil Armstrong took his giant leap for mankind. The Moon race was finally over. But there were still many unsolved mysteries about the Soviet space program that puzzled American intelligence analysts throughout the month. Had something gone spectacularly wrong at Tyuratam? What had happened? What did it mean?

| Even with the Moon race won, information on a major Soviet rocket failure was of interest to many senior political and military officials. |

When Jack Rooney made his loud exclamation at his light table at NPIC in mid-August, he attracted the attention of all his co-workers, who soon came over to look through his microscope and see what he saw. Rooney’s light table had an attachment that allowed him to make crude Polaroid images of the devastation at the launch pad and he passed around photos. The intelligence analysts, like most Americans, had watched their televisions with rapt attention as Neil and Buzz walked on the Moon. They were undoubtedly proud of the accomplishment. And then they went to work and saw the first-hand evidence of how poorly the Soviets were doing.

The CORONA was not a high-resolution system like the other American reconnaissance satellite the GAMBIT, but the damage to the launch pad was so big that the photo-interpreters looking through Rooney’s microscope could clearly see what had happened. The grillwork covering the trifoil flame trenches was blown away. One of the two adjacent lightning towers was also knocked down. The scorch marks spread all around the hole in the center of the launch pad. One other thing was clear: the explosion had occurred at Complex J, the large rocket pad, and not at Complex G, a sprawling series of smaller pads where the Soviets launched the SL-12/Proton with Zond spacecraft. The reconnaissance photography and the intercepted communications were consistent. A big puzzle piece had just fallen into place.

“It was my job to approve all cables that we sent out and also to approve all notes and briefing boards so that there was no confusion in the reporting in the intelligence community,” Dino Brugioni explained in an interview many years later. If there was a hot intelligence item, Brugioni would immediately brief his superiors at NPIC. He would then call the CIA’s Deputy Director for Intelligence (DD/I) and ask him if the item should be put on “hold”—in other words, not distributed—until after the President had been briefed about it. “I called the DD/I on J and the call I got back was to rush the two copies of the briefing boards that we made, one to the DD/I who briefed the President, and the other to the Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, who briefed the Secretary of Defense.” The Central Intelligence Bulletin of August 15 of the undamaged pad with the non-flight rocket on it photographed in June, and the lower-resolution CORONA image of the damaged launch pad, was undoubtedly part of this briefing process. Even with the Moon race won, information on a major Soviet rocket failure was of interest to many senior political and military officials.

Although by summer of 1969 there were many American intelligence assets focused on the Soviet space program, there were still significant gaps in information, leading to disagreements between analysts in different parts of the intelligence bureaucracy. But new information soon allowed the intelligence analysts to recalibrate their assessments.