Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true?by Dwayne Day

|

| One could ask why space settlement as an idea has been around for many decades now, has periodically increased in intensity, has not achieved any of its early key milestones, and yet still has adherents. Maybe that is because space enthusiasm is less about actual accomplishment than entertainment. |

A belief in space settlement shares many characteristics with religion (see “Mars ain’t the kind of place to raise your kids,” The Space Review, April 24, 2017). It is largely based upon emotion, although many of its adherents claim that it is based upon logic. In fact, some of the characteristics of this belief system are more akin to a cult. One of the surprising things about doomsday cults is that the failure of doomsday prophecies to occur does not usually destroy the cult and, in fact, can have the opposite effect, reinvigorating the faithful and reinforcing their devotion. This happens in many different ways, but a common one is the belief that something that the cult members did prevented, or more usually delayed, doomsday.

Without taking the analogy too far, one could ask why space settlement as an idea has been around for many decades now, has periodically increased in intensity, has not achieved any of its early key milestones, and yet still has adherents. Maybe that is because space enthusiasm is less about actual accomplishment than entertainment.

The concept of space colonies appeared in science fiction early in the 20th century but certainly became more common in stories in the 1950s and 1960s. This was probably coincident with the post-World War II rise in American power: increasing confidence in America and its scientific, economic, and cultural abilities allowed writers to take the existing mythology of Westward expansion and the American frontier and extend it outward. Take the example of Star Trek. The second episode aired in September 1966 and referred to an Earth colony. Numerous other episodes mentioned outposts and settlements. The concept of colonizing other worlds was already part of American popular culture.

But it was not until the 1970s that several writers and thinkers began to explore the possibility of actually building colonies in space, either free floating or on the Moon. In 1976 Gerard K. O’Neill published The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space. It was followed in 1977 by two other books: Stewart Brand’s Space Colonies, and T.A. Heppenheimer’s Colonies in Space. Americans had no problem with the word “colonization” because the country’s colonial experience was in the distant past and is generally positively viewed as prelude to the creation of the American nation. But many other parts of the world have a bad view of “colonialism,” viewing it as an exploitative relationship that they suffered under sometimes into the 1970s, with lingering effects all the way to the present.

Space activists were putting “colonies” in the titles of their books at the same time that groups in Africa were waging anti-colonial battles. Even today people in many nations in Africa, as well as places like India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, recoil at the word “colony.” If your goal is to spread the word about humanity’s future in space to non-Americans, using “colony” is not the best way to do it, and by the 1990s people in space activist communities largely switched to “settlement” rather than “colonization” in their writings. Notably, a 1977 NASA report was titled Space Settlements: A Design Study; perhaps ahead of its time in more ways than one.

But then space colonies… er, settlements, did not happen.

| Nearly 20 years after the creation of The Mars Society, we still do not have humans, let alone a settlement, on Mars. |

For those who were not alive back in the 1970s and 1980s it is impossible to make meaningful comparisons, but the enthusiasm felt by space activists was similar to that expressed today by people who believe that Mars One is going to establish an outpost on the Red Planet, or that Elon Musk is going to make his Interplanetary Transport System spacecraft real and start sending people out to build cities on Mars. Many people believed that NASA’s Space Transportation System was going to make spaceflight routine, easy and cheap, and that “ordinary people” (however defined) would soon be traveling in space and building industries, infrastructure and cities. The early members of the L5 Society were quite energetic and believed that big space stations were only a few decades away. Had you polled them at that time, most of them probably would have expected it to happen by the early twenty-first century, i.e. now.

There were always both positive and negative influences that shaped that early space settlement enthusiasm. Part of the reason that O’Neill and others embraced the space settlement idea when they did was because of world crises, both perceived and real. The most real aspect was the 1973 Oil Crisis, which fueled the view that the United States needed to seek energy independence, and space-based solar power was one way to do it. There were also numerous reports about over-population and pollution and resource depletion leading various people to propose that some solutions to these problems lie beyond Earth. The positive factors included a belief in American technological and economic abilities—even after the Vietnam War demonstrated the limits of American power, the culture of the United States still embraced optimism and can-do spirit.

Certainly the failure of the prophecy probably cost the movement—to the extent that it could be called a movement—some members. Some people probably gave up thinking about space settlement, going to L5 meetings, and proselytizing to their friends and coworkers. They found other things to occupy their time and their thoughts. Life went on. But others redirected their thinking and their writing. NASA and its Space Shuttle obviously were not going to produce space settlements, so they began looking for other ideas, technologies, and justifications to hitch their beliefs to.

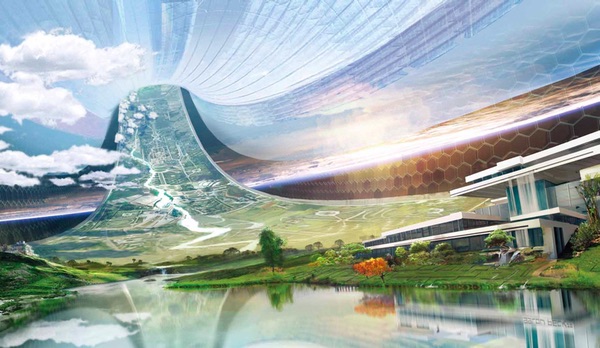

The space colony from the movie Elysium. We are no closer to such settlements today than we were 40 years ago. |

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s the National Space Society (NSS) sponsored its annual International Space Development Conferences. But the next substantial wave of belief in space settlement was really led by Robert Zubrin, who was briefly and tumultuously involved in the NSS before forming his own Mars Society in 1998. Throughout most of the 1990s, Zubrin spoke exuberantly about human settlements on Mars and gained a following.

| Now, over a decade and a half since this enthusiasm reached fevered pitch, we still have no space tourism, and all that discussion seems in retrospect to have been more of a diversion than actual progress. |

Like the earlier 1970s enthusiasm, it was fueled both by positive and negative factors: a belief that NASA was holding settlement back, coupled with an argument that it was possible to send humans to Mars relatively easily using existing technologies, and an appealing optimism about challenges and the human spirit. Another major Zubrin argument, that American society was culturally and technologically stagnant, probably found little foothold among Americans who were basking in the economically vibrant decade following the end of the Cold War and the dot-com boom. But enthusiasm for Zubrin’s vision also ebbed over time, as demonstrated by declining attendance at Mars Society conferences. Nearly 20 years after the creation of The Mars Society, we still do not have humans, let alone a settlement, on Mars.

By the first decade of the 21st century, the enthusiasm for space settlements took a bit of a detour with the advent of the idea of space tourism. This started with the late 1990s discussions of sending tourists to the Russian Mir space station and then with Dennis Tito’s flight to the International Space Station in 2001. The X PRIZE captured a great deal of publicity in the early 2000s. By the time it was won in October 2004, space tourism was white hot in the media and among space enthusiasts.

Over the next several years, space tourism dominated space enthusiast conferences and discussion boards. If you dig through Internet archives and early blogs from that decade, or records of talks at annual Space Access Society conferences, you can find many heated, lengthy discussions of space tourism. Its advocates argued that it was about to augur the era of space development both economically and technologically. Sure, the advocates argued, the early space tourists would all be rich people. But they would pave the way for the rest of us. And regular, daily flights, even of suborbital rockets, would enable the rapid development of new technologies that would make orbital flight even easier.

| Perhaps the best way to understand enthusiasm and support for space settlement is as entertainment, a sub-culture of science fiction fandom. |

Now, over a decade and a half since this enthusiasm reached fevered pitch, we still have no space tourism, and all that discussion seems in retrospect to have been more of a diversion than actual progress. In fact, all of the flown space tourists went to space in the previous decade, and the last experimental Bigelow space habitat (not funded by NASA) flew in June 2007. Yes, there are still new announcements, but there have always been announcements. There have also been substantial technical and public relations setbacks as well, such as the tragic accident in 2014 involving SpaceShipTwo. This was supposed to be the decade that space tourism became common, but we’re now seven years into the decade and that has not happened, and companies like Bigelow and Virgin Galactic have started pivoting toward new markets, like NASA and satellite launches, neither of which the enthusiasts of the last decade would have looked forward to with, well, enthusiasm.

So where has the movement for space settlement shifted? Clearly it has attached itself to Elon Musk, and SpaceX’s impressive technical advances have at times caused people to swoon. Musk’s talk last fall demonstrated how enthusiastic some people are about his vision of sending humans to Mars: attendees ran into the auditorium when the doors were opened, and one questioner wanted to ascend the stage to kiss her idol. You do not have to search hard to find fevered comments on the Internet about the space settlement wave that many people believe, once again, is almost here. People regularly argue that the cost of accessing space is about to drop by many orders of magnitude, opening up the space frontier (SpaceX’s current discount on reusable launches is a bit more modest.) They also admit that although Musk’s prediction of landing humans on Mars by 2024 might be a tad bit optimistic, he’ll almost certainly do it, just a few years later. So, perhaps humans on Mars in a decade, and the first settlement under construction a couple of years later?

We have heard this tune before.

For those of you keeping track: the 1970s visions of space settlements have not come true after four decades; the 1990s visions of Mars settlements have not happened after two decades; and the fevered discussions a decade and a half ago of a vibrant space tourism market still have not happened. Concept, enthusiasm, no actual payoff. Rinse, dry, repeat. But certainly this time will be different, right?

Perhaps religion is not the best way of understanding the enthusiasm for space settlement. It is hard to call it a “movement” when it is so small, fractured, and lacks a clear manifesto. So perhaps the best way to understand enthusiasm and support for space settlement is as entertainment, a sub-culture of science fiction fandom. Is it significantly different than sitting in a theater and watching Elysium with its giant rotating space station, or The Expanse, with its colonies on Mars and in the asteroid belt? Admittedly, those are passive activities, sitting and watching, but how much more active is being “involved” in space settlement activities?

Somebody once observed that most of the people who play Powerball when the jackpot is in the hundreds of millions know that they will not win. But buying a ticket is permission to fantasize what they would do if they won. Maybe the same is true about most space enthusiasts—they participate, whether it is going to a conference, blogging, or just endlessly posting on discussion boards and comment sections—because it is permission to believe that the dream can indeed be real, even if deep in their hearts they know that not to be true.

| There is no reason to believe that the failure of space nirvana to occur will substantially undermine the faith and enthusiasm for space nirvana. |

The desire for world-building is a major aspect of space enthusiasm. You can see it in essays where somebody redesigns the human spaceflight program to suit their own vision of what is best even if they lack qualifications to make actual decisions about life support, space medicine, and contracting. Like grandpa in the basement with his model train set, they get to control a projection of what the world would be, should be like—if only they were in charge. Plumbers, programmers, and podiatrists by day, in the evening they write 10,000-word essays where they describe what the space program should look like. It’s easy: start by abrogating the Outer Space Treaty, then rewrite the federal acquisition rules, and eventually move on to the back-of-the-envelope calculations of launch costs and return on investment. Anybody can do it, and then gripe about the fact that it is not already happening. As a character in a recent episode of The Simpsons declared, “I wanted to be someone who’s bravely going to Mars eventually.”

Ten years from now, in the incomprehensibly futuristic-sounding year of 2027, where will we be? Will humans be romping around Mars? What about 2037? Settlements in 20 years seems to be optimistic even for the optimists, but what if no humans have landed on Mars in 20 years? What then? Remember: the failure of doomsday prophesies rarely undermines doomsday cults, so there is no reason to believe that the failure of space nirvana to occur will substantially undermine the faith and enthusiasm for space nirvana. Even when those future days fail to live up to the expectations of people dreaming about them right now, one thing is certain: there will still be people dreaming that the space settlement future is just on the cusp of happening. Really soon. Just wait a little bit longer…

So to answer the question in the headline: no, the dream is not a lie when it fails to come true. That’s not why the dream exists.