Next Christmas in the Kuiper Beltby Jeff Foust

|

| “This is not a simple, spherical object,” said Buie of 2014 MU69. “There’s something weird going on with this object.” |

“You should spend your New Year’s Eve with NASA at the John Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab,” said Alan Stern, principal investigator of NASA’s New Horizons mission, during a briefing last month at the Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) in New Orleans.

Stern and other members of the New Horizons team will be at APL next New Year’s because that date marks the next major milestone for the mission: the flyby of a Kuiper Belt object known only, for now, as 2014 MU69. (The object will get an unofficial “nickname” in the coming months, the result of a naming contest run by NASA and the mission, although a formal name sanctioned by the International Astronomical Union may not come until after the flyby.)

The flyby is the highlight of a five-year extended mission approved by NASA in 2016 after New Horizons completed its primary mission, a flyby of the dwarf planet Pluto, in 2015. “We’re on an extended mission through 2021 to explore the Kuiper Belt in a whole host of ways,” Stern said, including telescopic observations of dozens of objects the spacecraft will pass at a distance.

The centerpiece of the extended mission, though, will be the flyby of 2014 MU69, with the closest approach taking place shortly after midnight Eastern time on January 1, 2019.

Astronomers discovered 2014 MU69 in observations by the Hubble Space Telescope in the summer of 2014 devoted to looking for objects that were in range of New Horizons for a post-Pluto flyby. When the mission selected the object as its target for a potential extended mission in 2015, scientists believed the object was a body about 50 kilometers across.

It turns out 2014 MU69 is far more complex than they originally thought. “This is not a simple, spherical object,” said Marc Buie of the Southwest Research Institute. “There’s something weird going on with this object.”

That assessment came from a campaign led by Buie in mid-2017 to observe stellar occultations by 2014 MU69, when the object briefly blocked the light from a distant star as seen on a narrow track on the Earth. In early June, a series of portable telescopes were set up in South Africa and Argentina to observe one such occultation. However, none of the telescopes saw anything; Buie said it turned out the telescopes were in the wrong place, based on what they now know is the orbit of 2014 MU69.

Another occultation took place in mid-July, also visible from Argentina. This time, the telescopes were in the right place, and several of them observed the occultation. “We hit the jackpot,” he said.

| “It’s going to be a very interesting time around the holiday season next year as we’re learning in real time what this system is like, and whether we can fly the close trajectory that we want,” Spencer said. |

The immediate analysis of those observations revealed an irregular shape for 2014 MU69, raising the possibility that the object was a binary, with two objects either closely orbiting each other or in physical contact (see “The past and future of outer solar system exploration”, The Space Review, September 11, 2016).

That assessment remains the most likely explanation for the occultation observations. “We think there were two objects,” Buie said. “I prefer the contact binary in this particular case.” He added that it could be a single elongated “potato-like” object, but was skeptical that was the case for an object this large.

In between the two ground-based observing campaigns was one by NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), a Boeing 747 with a 2.5-meter telescope mounted in its fuselage for high-altitude observations. It attempted to observe the occultation of another star on July 10 above the South Pacific.

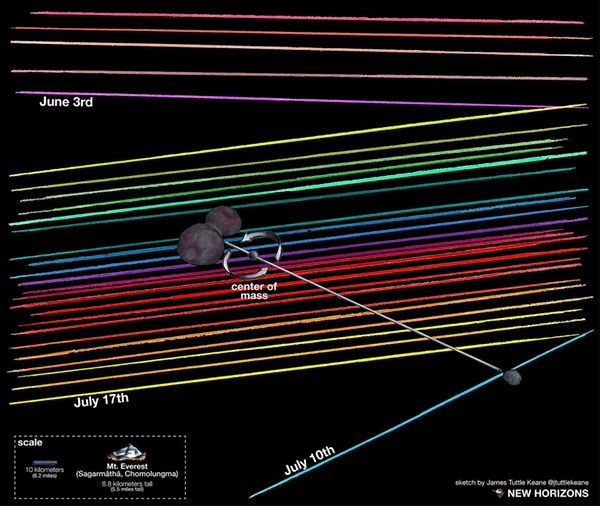

Buie said they did observe an occultation, but later analysis showed that the blip they saw did not take place where 2014 MU69 was predicted to be. He said they believe what they saw was real, but was caused instead by a separate small object: perhaps a moon orbiting the binary. That would also explain, he said, why the occultation of 2014 MU69 observed later in July was slightly off the predicted position, which represents the center of mass.

“It’s almost like we’ve got three objects in one here,” he said. “This is very exciting.”

The occultations observed over the summer of 2017, represented by the various lines above, could be explained if 2014 MU69 is a binary with a small moon orbiting it. (credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/James Tuttle Keane) |

While scientifically exciting, it poses a challenge to the upcoming flyby. If there’s one moon orbiting 2014 MU69, there’s the potential for more, as well as smaller debris that could pose a hazard to New Horizons as it flies past the object.

For now, there’s little for the mission team to do but to plan for various contingencies. There is one more occultation by 2014 MU69 that could be observed prior to the flyby, on August 4. The occultation’s narrow path takes it across parts of Colombia and Venezuela, making landfall again near Dakar, Senegal, and extending across West Africa.

“It’s not the best spot in the world for us to be doing this, but it’s not hopeless, either,” Buie said. There are active discussions with observers in Colombia and Senegal about trying to observe it, he noted. Attempting to observe both the main object and its apparent moon requires a large number of telescopes, densely arrayed. “Getting both is going to be a really big stretch, but I think it’s worth giving it a shot.”

“If anybody can do it, it’s Marc and his team,” Stern added, calling the 2014 MU69 observations “the toughest occultation ever attempted.”

After that, it will be up to the instruments on New Horizons itself to scout its destination. The object should first be visible to the spacecraft in September, said John Spencer, deputy project scientist for the mission. Once visible, he said they’ll use New Horizons’ instruments to confirm the presence of the moon from the occultations, as well as look for any additional moons or “hazardous material” surrounding it.

That information will help the mission team determine what trajectory the spacecraft takes during the flyby. The preferred approach would bring New Horizons as close as 3,500 kilometers from 2014 MU69, much closer than the spacecraft got to Pluto. That will enable much sharper images of the object.

Hal Weaver, the New Horizons project scientist, said that the best resolution of Pluto from New Horizons was 70 meters per pixel on a limited swath. On its planned trajectory, New Horizons should be able to return images at 30 meters per pixel across the entire sunlit side of the object.

“It’s pretty hard to beat what New Horizons did during the Pluto flyby, but one way that MU69 will do better is with spatial resolution,” Weaver said.

However, if the images New Horizons returns in the months leading up the flyby show hazards, or there remain significant navigation uncertainties, the mission could elect to take an alternate trajectory that brings it no closer than about 10,000 kilometers from 2014 MU69.

Alice Bowman, the mission operations manager for New Horizons at APL, said there will be nine opportunities for trajectory correction maneuvers, from early October until December 22. A final decision on what flyby trajectory to take, she said, will be made in mid-December. “That will come just a week before the nine-day flyby sequence will start,” she said.

“It’s going to be a very interesting time around the holiday season next year as we’re learning in real time what this system is like, and whether we can fly the close trajectory that we want to fly or if we have to do this deflection,” Spencer said.

| “Besides being the farthest exploration in this history of humankind, this flyby is also going to the most primitive and pristine object ever explored,” Stern said. “We’ve really never been to anything like this.” |

During the flyby itself, New Horizons will return data late December 30 and early December 31, and then provide a “status check” around 10 am EST January 1. That will be followed by a couple of downlinks of data later that day and January 2, before a solar conjunction—the Sun coming directly in line between the Earth and the spacecraft—limits communications for several days.

Returning all of the data that New Horizons collects will take many more months, given the spacecraft’s limited power and increasing distance from Earth. “We don’t expect to finish up the data transmit until August or perhaps September of 2020,” Stern said. That means a trickle of data, and discoveries, for more than a year after the flyby. “So the news will just keep raining down from the Kuiper Belt.”

The data that does gradually come back will help answer questions about the structure and composition of 2014 MU69, said Anne Verbiscer, New Horizons assistant project scientist. One area of interest is understanding what makes the surface of the object both very dark and much redder than Pluto. After the flyby, backlit observations of the object will help spot any traces of a comet-like coma or other gases being released by it.

2014 MU69 is particularly interesting because scientists believe it is a relic from the early history of the solar system, largely unaltered in the subsequent billions of years. “Besides being the farthest exploration in this history of humankind, this flyby is also going to the most primitive and pristine object ever explored,” Stern said. “We’ve really never been to anything like this.”

What happens after New Horizons completes that data downlink in late summer of 2020 isn’t clear yet. A few months earlier, Stern sounded upbeat about the odds of performing a flyby of another Kuiper Belt object, saying there was “a fighting chance” of such a flyby. At the AGU meeting in December, though, Stern sounded less optimistic.

“There is a small chance that we might find another object to fly by, but our fuel supplies are very low,” he said, “and so the great probability is this will be the last flyby for New Horizons. That said, we will certainly look.”

Even without another flyby, Stern said New Horizons has enough fuel, and power from its radioisotope thermoelectric generator, to operate into the mid-2030s and perhaps later. The spacecraft, he said, could continue to carry out planetary science research in the Kuiper Belt, and also serve as a platform for astrophysical and heliophysical observations.

“There’s a lot of good science to do,” he said. “I expect New Horizons will have a series of successful proposals to NASA over the years, and continue in the great tradition of the Pioneers and Voyagers to keep exploring further and further outwards.”

First, though, New Horizons needs to get through the 2014 MU69 flyby that will keep the mission team and others busy through the holiday. (Media covering the flyby, Stern said, will be allowed to bring their families with them to APL over New Year’s, “so you don’t have to choose between your family and covering this historic flyby.”)

“Spend your Christmas in the Kuiper Belt,” he said. “It’s going to be exciting, and there’s not going to be anything like it again.”