Space, and the stories we tell ourselvesby Dwayne A. Day

|

| The curators and exhibit designers for Delaware North, which runs the KSC Visitor Complex, are perpetually dealing with America’s changing current human spaceflight goals. |

People don’t just accidentally show up at the Kennedy Space Center. They go there because they have an interest in the subject of spaceflight. They could easily stay in Orlando and visit yet another amusement park, but they head out to the Space Coast because it somehow, in some way, attracts them. And the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex does an excellent job telling a story, within limits, and with a distinct patriotic and philosophical message. The Visitor Complex is certainly an entertainment center, with much more of an educational and inspirational mission than Disney World. But the Visitor Complex has to tell stories that may be in motion and change soon after displays and videos are unveiled. It is not a museum. And until recently, the Visitor Complex sought an almost entirely upbeat message, with barely a hint of the negative stories of spaceflight. Recent additions to the Visitor Complex now expand the boundaries of its inspirational mission, and raise the issue of the ethical responsibilities of an attraction that exists foremost to make money and to entertain rather than educate.

The curators and exhibit designers for Delaware North, which runs the KSC Visitor Complex, are perpetually dealing with America’s changing current human spaceflight goals. Telling the story of what is happening at KSC is the Visitor Complex primary task, but sometimes that can be a challenge. Back in 2010, I remember seeing some newly installed panels and exhibits devoted to the Ares I and Ares V rockets and the Constellation program—all of which had just been canceled. It must have driven the designers mad having spent all that time and money to present what had quickly become an outdated story of America’s space plans. A year or two later the Visitor Complex had adjusted. They kept some of the same displays, like a lunar landing simulator, but changed the focus and the signage to NASA’s “Journey to Mars.” Today the Visitor Complex has an entire building labeled “Journey to Mars” even though NASA’s “Journey to Mars” rhetoric—not to mention program planning—has all but disappeared. Will they have to change the signage soon, or is “Journey to Mars” sufficiently vague to endure a bit longer?

The Visitor Complex is no stranger to these emerging anachronisms caused by the shifting sands of America’s human spaceflight program, and they crop up in almost everything they do. A video on the Visitor Complex’s bus tour mentions NASA’s plans to travel to an asteroid and retrieve it—another mission that no longer exists. Astronaut Charles Bolden supplied the narration for a space shuttle attraction only shortly before he was named as NASA administrator, and for years most visitors were probably oblivious to the fact that the friendly guy they saw describing the space shuttle was now running NASA. A video featuring schoolkids enthusiastically talking about what they want to do in space does not feel dated, although all the early teenagers in it are now at least in their late twenties. Did they continue to aspire to become astronauts and explorers? Do some of them currently work for NASA, ULA, or SpaceX? Have they earned degrees in engineering or geophysics or astronomy? Or are they all now doing non-space jobs? It doesn’t really matter, because they were there to espouse generic, if rarely examined, platitudes about spaceflight. The more generic the statement, the longer it can endure. It’s only when you get specific that you can run into challenges.

Where the KSC Visitor Complex excels is at depicting the past glories of the American space program, and the past shifts less than the present. The most recent addition to the Visitor Complex is the Heroes and Legends building, with the US Astronaut Hall of Fame, opened in November 2016. The building features a 3D show complete with wind and sound effects and depicts such events as the launch of Alan Shepard and the thruster malfunction on Gemini 8 that nearly killed Neil Armstrong and Dave Scott until Armstrong did some of that level-headed piloting that made him a legend. Some of the show is a bit ham-fisted, with characters delivering expository dialogue—telling rather than showing. The display hall itself explores the qualities of heroism such as curiosity and perseverance and does a decent job of turning an overused and misused word into a set of actions that can be examined and hopefully emulated by the visitors.

| Missing from both the Florida and Washington DC exhibits are any of the discussions that today’s historians like to engage in, like the social context and the costs of these endeavors. |

Prior to the addition of the Heroes and Legends attraction, the major addition to the Visitor Complex was the Space Shuttle Atlantis building. It’s a remarkably well-designed attraction that starts with showing visitors a movie about the early design of the space shuttle, then reveals Atlantis itself. Nearby are displays about the shuttle program, the numerous shuttle missions, the Hubble Space Telescope, the International Space Station, and various aspects of the shuttle’s operations. The designers ingeniously found ways of using the interior design to tell part of the shuttle story.

Although the Space Shuttle Atlantis building is about as good an overview of the shuttle program as one can get, it still dims compared to the Apollo/Saturn V Center located on KSC itself. That building opened only a few years after the highly successful 1995 movie Apollo 13, and was clearly inspired by it in various ways, from the overall heroic atmosphere, to the symphonic score that plays throughout the center, to a video narrated by James Lovell. The Apollo/Saturn V Center remains an outstanding museum achievement two decades after it opened. It still looks and feels modern and new. It stands in sharp contrast to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s creaky and woefully obsolete Apollo gallery. Delaware North charges for access to its facilities, enabling it to update the displays, whereas the Smithsonian is free. But the Smithsonian Apollo gallery has not been updated in decades and now has the opposite effect compared to the Florida attraction, creating a bleak and depressing introduction to Apollo for visitors who probably know nothing about it.

Missing from both the Florida and Washington DC exhibits are any of the discussions that today’s historians like to engage in, like the social context and the costs of these endeavors. Apollo was not just a Cold War competition. It was a huge expenditure at a time when the nation was fighting a major war overseas and experiencing social unrest at home. And despite what space enthusiasts believe, the majority of the American public only briefly supported it. If you were to design an Apollo exhibit from the ground up today, you would have to mention these other things, discussing what was going on in the United States at the time, including such things as protests against the program from civil rights activists and the massive expenditure of resources. As it stands, the Apollo/Saturn V Center is a monument to engineering and willpower and bravery, but it leaves many other stories untold.

Part of the genius of the Apollo/Saturn V Center’s design is how it shows, rather than tells, what happened, exposing visitors to a launch simulation and then exiting them beneath the massive Saturn V’s F-1 engines. For many it is the first time they get a sense of just how big that rocket was. As they walk forward they can stop at displays that explain various aspects of the program and the missions. All the way at the far end of the building, at the front end of the rocket, visitors now reach one of the newest attractions at the KSC Visitor Complex, and this one finally—after all the rah rah boosterism and heroic music and inspirational stories—finally, exposes them to some of the human costs of the Apollo program.

The Apollo 1 exhibit at the KSC Visitor Complex includes artifacts from the three astronauts killed in the fire. (credit: D. Day) |

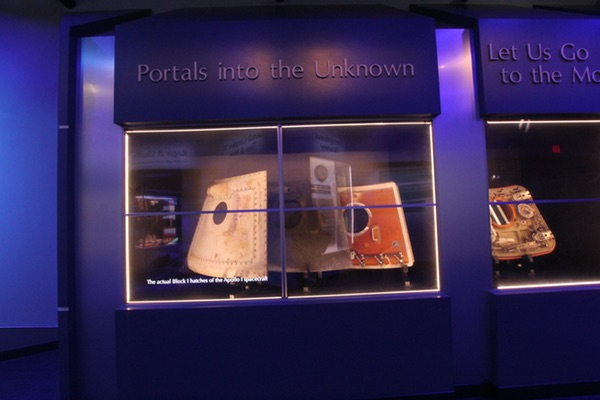

At the front of the rocket, wrapped around the launch tower gantry, is the Apollo 1 Tribute that was opened in January 2017. From a historical or educational perspective, this new addition is relatively minimal, just a few displays and videos, but the fact that it exists at all is remarkable when one understands just how NASA and the American public have dealt with their space tragedies.

NASA has long treated its accidents and the astronauts who died in them with a combination of embarrassment and reverence, but rarely with a sense of duty and education. The accidents get rooted in the past, rarely with any consideration for what they can tell us for planning our future. For example, the Challenger debris was buried in a silo at Kennedy Space Center a few years after the accident. One of the things that shocked me and my fellow investigators while working on the Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB) in 2003 was that NASA did not study the Challenger accident or teach its lessons to its new hires. We learned that only a few months before the Columbia accident a joint NASA-Navy working group had highlighted the fact that, while Navy safety experts studied the Challenger accident for insights into how to improve safety, NASA did not. When Diane Vaughn, who had written an important book about the Challenger accident, informed us in spring 2003 that she had never been invited to NASA to talk about her book’s conclusions, we urged her to say that publicly during one of the CAIB’s hearings. She did, and was immediately invited to NASA Headquarters. A desire to move on, coupled with a desire to not offend astronauts’ families, has meant that the agency has barely talked about what happened and why it happened for its past accidents, including Apollo 1. It took half a century before the Visitor Complex installed a serious tribute, and short narrative, about the Apollo 1 fire. Clearly the emotions that lurked just under the surface still ran hot, and limited any discussion of what happened and how it can inform our actions today.

| NASA has long treated its accidents and the astronauts who died in them with a combination of embarrassment and reverence, but rarely with a sense of duty and education. The accidents get rooted in the past, rarely with any consideration for what they can tell us for planning our future. |

The Visitor Complex’s Apollo 1 exhibit uses some cutting-edge and impressive technology—video screens that become transparent to reveal artifacts behind them—to tell brief stories about the three astronauts before displaying some objects that were either owned by the astronauts or depict their lives and interests. These include objects such as military uniforms and airplane and car models. The most emotionally and symbolically loaded object on display, however, is the Apollo 1 Command Module hatch, which was overly complicated and which the astronauts struggled unsuccessfully to open during the fire. The hatch is the most symbolic object of the Apollo 1 fire. After all, if the hatch had been designed to open faster, the astronauts would have escaped. Next to it is an example of the redesigned Apollo hatch which could open much more quickly. Much harder to tell, especially in a museum setting, is the history behind the engineering decision to use an all-oxygen atmosphere on Apollo, or how creeping quality control problems at contractor North American Aviation, and poor NASA oversight, contributed to the fire. Visitors who wish to know more about the Apollo 1 accident will have to do their own research to find out, and hopefully this new exhibit will prompt at least a few people to do exactly that.

The Apollo 1 exhibit includes the hatch whose complex design doomed the astronauts. (credit: D. Day) |

There is an interesting counterpoint to this Apollo 1 tribute on the other side of the country. On board the USS Iowa Museum in the Port of Los Angeles is a brutal, graphic display of a tragedy that happened two decades after the Apollo 1 fire. The battleship Iowa suffered a devastating turret explosion in 1989 that claimed the lives of 47 sailors. Recently the museum added an exhibit devoted to the explosion that features a video showing some of the burned sailors being removed from the turret. The exhibit also features a discussion of the botched Navy investigation of the accident and their conclusion that the explosion resulted from sabotage. The displays also discuss the now widely accepted theory that the turret explosion was probably accidental, sharing characteristics with earlier naval gun turret explosions.

The Iowa Museum’s graphic and blunt description of a tragedy was a bold decision, the kind of decision that may anger some of the families of the dead and does not make the Navy look good. What makes the contrasting approaches between the Apollo 1 and Iowa displays even more unusual is that the Iowa incident is much more recent and involved more people. But the Apollo astronauts who died were household names at the time, whereas the Iowa sailors were not. It would be fascinating to hear the designers of the Iowa’s exhibit and the designers of the Apollo 1 Tribute explain how they decided to depict these tragedies, but there are still family sensitivities that would limit that discussion. In a nation that still argues over how best to discuss the Civil War over a century and a half after it ended, it is no surprise that events of only a few decades ago, where direct family members are still alive, can present major challenges to story tellers.

| There is no perfect way to tell these stories, they will always be told partially, and with human biases, foibles, lies, and inevitable errors. But just because that is true does not mean that we should not try. |

But although these are difficult stories to tell, avoiding them entirely is not simply an easy and simple option, but a bad choice which comes with potentially negative consequences. NASA’s past accidents remain valuable, if largely unexplored, learning experiences. Admittedly, a museum or visitor’s center is not the only method for communicating lessons or starting a conversation, but it can offer opportunities that other forums cannot, exposing difficult subjects to broader audiences, and making the abstract past seem tangible… and present.

Marcel Proust, in Remembrance of Things Past, was interested in how objects inspire memory when he wrote:

When from a long distant past nothing persists, after the people are dead, after things are broken and scattered, still alone, more persistent, more faithful, the smell and taste of things remain poised a long, long time like souls, ready to remind us, waiting, hoping for their moment amid the ruins of all the rest, and bear unfaltering in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence the vast structure of recollection.

Thus, we need not only history books, but things to make the past real to the citizens of the present. There is no perfect way to tell these stories, they will always be told partially, and with human biases, foibles, lies, and inevitable errors. But just because that is true does not mean that we should not try.

And perhaps it’s not only Americans who need the space history lessons. At one point while standing in line for the exhibit on space heroes, I noticed that a young couple was standing next to me speaking to each other in Russian. I don’t know what they were saying, but the guy must have been talking about astronauts. After all, I heard him mention that great American astronaut “Louie Armstrong…”