God’s eye view: HEXADOR and the very high resolution satelliteby Dwayne A. Day

|

An RF-8 Crusader from the same reconnaissance squadron that flew dangerous missions over Cuba during the 1962 missile crisis. (credit: US Navy() |

By 1968, with both the HEXAGON and the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL)/DORIAN reconnaissance satellites under development, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) had its hands full working on the next-generation satellite reconnaissance systems. Both spacecraft were big—requiring powerful Titan III launch vehicles to put them in low Earth orbit—and both were also complicated, expensive, and over-budget. So it is surprising that amidst all this work, some within the NRO began discussing developing yet another photographic reconnaissance satellite program, one which remains relatively obscure and little known even today, over five decades later. This program was known as the “Very High Resolution” or VHR reconnaissance satellite, and at least one iteration appears to have been referred to by some as HEXADOR, as a combination of HEXAGON and DORIAN hardware. VHR was supposed to take the kinds of photographs that the RF-8 Crusaders had taken six years earlier, but in areas of the world that no Crusader could fly.

| The major unknown is what was behind the VHR requirement—why did the satellite have to be so powerful? What were they looking for? |

The VHR program is referenced in only a few declassified NRO documents and histories. It was never formally a “program,” but instead was at most a series of studies. When and where it started is unclear, but it appears that the first discussion of VHR began in 1968. Declassified documents do not yet indicate why some members of the intelligence community believed that a significantly higher resolution satellite was required despite the already impressive planned performance of the MOL/DORIAN, but the Cuban Missile Crisis was certainly a good case study on the value of better photography.

Part of the difficulty of discerning VHR’s origins is that the capabilities of some of the NRO’s reconnaissance satellites at that time remain classified. The CORONA search satellite had at best six-foot (1.8-meter) resolution and was scheduled to be replaced by 1970 or 1971 by the HEXAGON, with resolution of 1–3 feet (61–91 centimeters). The GAMBIT-3 (also referred to as the KH-8) entered service in 1966 and its resolution was apparently initially around two feet (61 centimeters), improving to 12 inches (30 centimeters) relatively quickly. The goal for the Manned Orbiting Laboratory and its big DORIAN optical system was around six inches (15 centimeters) resolution on the ground, possibly up to four inches (10 centimeters) if viewing conditions were ideal. The Very High Resolution satellite then being discussed in 1968 was intended to have resolution better or equal to DORIAN, and its existence while MOL/DORIAN was still ongoing indicates that those advocating for it did not believe that MOL would fulfill the requirement. The major unknown is what was behind the VHR requirement—why did the satellite have to be so powerful? What were they looking for?

The driving force for this higher resolution was apparently (the evidence is weak) the Soviet Union’s burgeoning anti-ballistic missile program. For several years, controversy had reigned within intelligence and military circles about what threat Soviet ABMs posed to American ballistic missiles. (See: Chris Manteuffel, “An enigma behind the iron curtain: the Tallinn anti-ballistic missile system and satellite intelligence,” The Space Review, March 18, 2019) Although Soviet ABM radars were massive and easy to spot in reconnaissance satellite photos, the missiles were not. Intelligence analysts wanted the capability to see the missiles and their control surfaces (i.e. their fins), which would provide an indication of whether they were intended for high altitude interceptions, or were aimed at an aircraft flying at medium altitudes. Seeing such small details from space required a powerful satellite.

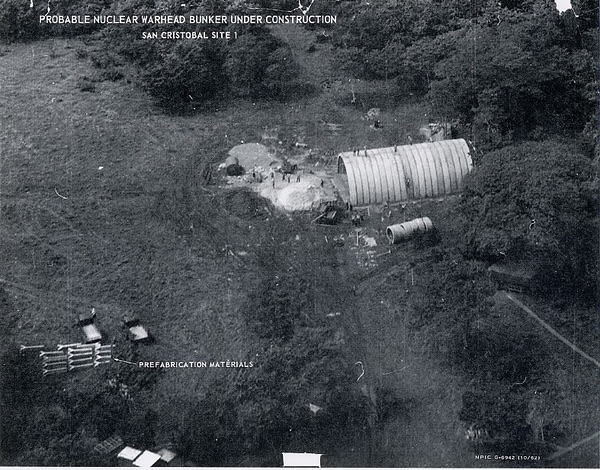

According to a study from November 1968 that has yet to be declassified but is quoted in a recent NRO book: “During the Cuban missile crisis, the value of VHR photography to provide easily understood and incontrovertible evidence for national decision making was clearly demonstrated.”

The term “incontrovertible evidence” is a complicated one. One of the fascinating aspects of the Cuban Missile Crisis is how much faith Kennedy put in the intelligence advisors who were telling him that the blurry shapes they saw in early U-2 reconnaissance photos of the island were ballistic missiles. Kennedy trusted them. But he also approved low-flying RF-8 Crusader flights that soon zoomed over Cuban weapon sites at high speeds and treetop level. Their side-looking cameras produced much better images than the admittedly impressive cameras on the U-2s, and from an angle rather than directly overhead. These photos had significant value. They made it easier for senior decision makers like Kennedy to understand what was happening on the ground in Cuba and to see structures from closer to ground level. When the better photos came back, Kennedy and his senior advisors could trust their own eyes and not just the intelligence analysts.

But the photographs also helped interpreters back in Washington identify equipment that they had seen in U-2 and satellite images of missile sites in the Soviet Union. Whereas it was common for higher power cameras to be accompanied by “index” cameras that could take photos of larger areas to provide context—particularly location and the relationship of different structures and objects to their surrounding facilities and terrain—the Crusader images demonstrated that high resolution imagery could help provide context for lower resolution images, making it possible to identify blurry objects in the lower resolution images. Certainly a VHR satellite could help do this globally: once one missile site was imaged in high resolution, other sites imaged at lower resolution could be better interpreted.

Low-altitude reconnaissance photograph taken by an RF-8 Crusader over Cuba during the October 1962 missile crisis. Such high-resolution photos greatly aided decision makers in understanding what was happening on the ground. (credit: US Navy) |

When Richard Nixon was sworn in as president in January 1969, he wanted to reduce government spending and ordered people in his administration to pursue budget reductions. With the Vietnam War costing huge amounts to fight, military and intelligence budgets came under greater scrutiny than before. The intelligence budget problem was looking tight by early 1969, with many projects vying for funding including HEXAGON, the Manned Orbiting Laboratory and its DORIAN optics system, and the proposed Very High Resolution system. According to a declassified history, VHR was still not defined and could be an entirely new system, a modification of GAMBIT, or a combination of GAMBIT, HEXAGON, and DORIAN hardware. One version of this was briefly known as HEXADOR. HEXADOR would have used the large DORIAN optics and a HEXAGON satellite vehicle and reentry systems.

Also under discussion were various proposals for a near-real-time satellite system that could send back imagery to the ground within hours, compared to the days that it took to get back film from CORONA and GAMBIT. But to some people within the intelligence community, near-real-time reconnaissance was a less urgent requirement than very high resolution reconnaissance that took longer to reach interpreters.

In March 1969, Nixon canceled the HEXAGON program in favor of MOL and its DORIAN camera system. CIA director Richard Helms also appealed to Nixon on behalf of HEXAGON and Nixon reinstated the program. In June 1969, Nixon canceled MOL.

| “During the Cuban missile crisis, the value of VHR photography to provide easily understood and incontrovertible evidence for national decision making was clearly demonstrated.” |

While this debate over HEXAGON and MOL was underway, there were also discussions of other possible satellite programs not yet in full-scale development. In May 1969, highly respected intelligence advisor Edwin “Din” Land wrote President Nixon recommending that he cancel MOL and continue development of a very high resolution camera that exploited DORIAN technology advances. Land also urged that most reconnaissance research and development be concentrated on near-real-time reconnaissance. He urged Nixon to start “highest priority” development of a “simple, long-life imaging satellite, using an array of photosensitive elements to convert the image to electrical signals for immediate transmission,” a system that the CIA was then developing known as ZAMAN. (See “Intersections in Real Time: the decision to build the KH-11 KENNEN reconnaissance satellite (part 1)”, The Space Review, September 9, 2019, and Part 2, September 16, 2019.)

By August 15, the NRO leadership had finally developed a consistent position after months of indecision: conduct a two-year technology advance program for the ZAMAN near-real-time reconnaissance system, and avoid full program approval until technology uncertainties had been resolved. John Foster, Director of Defense Research and Engineering, believed that high-resolution reconnaissance was a more important requirement than near-real-time, but also believed that either a modified GAMBIT or the HEXADOR approach would be suitable for this mission—in other words, whereas ZAMAN required further technology development, the technology for VHR already existed, it just needed to be assembled in a satellite.

The VHR concept apparently continued for another year and a half before ending in spring 1971. In April 1971, Director of the NRO John L. McLucas wrote a memo titled “Future of Drones and Aircraft in Overhead Reconnaissance” where he discussed the limited utility of drones and aircraft such as the U-2, particularly when it came to overflying hostile territory. McLucas explained that the approach the NRO was taking to improve the ability to return imagery faster was to have a satellite in orbit constantly, with the ultimate goal being the deployment of a near-real-time satellite using an electro-optical imaging system that beamed its images to the ground.

| By 1971 the NRO should have realized that 2.5-centimeter (1-inch) ground resolution wasn’t possible because it defied the laws of physics. |

The new electro-optical imaging system, soon named KENNEN, was also going to cost a lot of money. “In order to acquire such a capability, which is some three or more years away, constraints have caused us to terminate all activities leading to a Very High Resolution system capable of some 1” to 5” resolution” (2.5–12.7 centimeters), McLucas explained.

But by the latter 1960s it was known within the reconnaissance community that there was a physical limit to resolution from a satellite due to atmospheric turbulence, and the lower-end number that McLucas cited as VHR’s goal was impossible to achieve.

In 1966, David Fried published a paper in the open literature that determined the atmospheric resolution limits of a satellite in low Earth orbit. Fried calculated that a satellite was limited to a resolution of no better than 5–10 centimeters no matter how powerful its optics, and his conclusion was independently confirmed two years later by John C. Evvard. By 1971 the NRO should have realized that 2.5-centimeter (1-inch) ground resolution wasn’t possible because it defied the laws of physics. Available technology, or even technology that might become available in the foreseeable future, could not bend the laws of physics. By the 1970s, the GAMBIT-3 satellites provided an existence proof when they returned the best imagery ever obtained up to that time, around 2.3 inches (5.8 centimeters), which operators accomplished by flying the satellites at low altitudes before reboosting them (although at very low altitude the satellite shook so much from atmospheric drag that it negated the advantage of being closer to the target).

McLucas’ memo indicates that VHR was killed by budget constraints, not physical limits. Thus, VHR’s existence, and demise, remain a mystery, and only future document declassifications will illuminate this subject.

For more information on the RF-8 Crusader missions over Cuba see: Captain William B. Ecker and Kenneth V. Jack, Blue Moon Over Cuba: Aerial Reconnaissance during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.