Ekipazh: Russia’s top-secret nuclear-powered satelliteby Bart Hendrickx

|

| Called Ekipazh, its mission may well be to perform electronic warfare from space. |

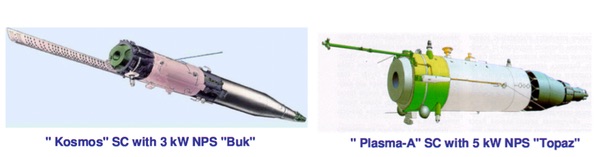

KB Arsenal, based in St. Petersburg, is no newcomer to the development of nuclear-powered satellites. In the Soviet days it built satellites known as US-A (standing for “active controllable satellite”), which carried nuclear reactors to power radars used for ocean reconnaissance (in the West they were known as “radar ocean reconnaissance satellites” or RORSAT for short.) The satellites had been conceived in the early 1960s at the OKB-52 design bureau of Vladimir Chelomei before work on them was transferred to KB Arsenal at the end of that decade. The satellites’ three-kilowatt thermoelectric reactors, known as BES-5 or Buk, were built by the Krasnaya Zvezda (“Red Star”) organization. The US-A satellites operated in low Earth orbits at an altitude of roughly 260 kilometers and, after finishing their mission, the reactors were boosted to storage orbits at an altitude of about 900 kilometers. However, three of the satellites (Cosmos 954, 1402, and 1900) experienced problems with the boost maneuver; the first showered radioactive debris over northwestern Canada in January 1978. The program saw a total of 37 missions between 1965 and 1988.

In 1987 KB Arsenal launched two experimental satellites named Plazma-A (officially announced as Cosmos 1818 and 1867) equipped with five-kilowatt thermionic reactors of Krasnaya Zvezda variously called TEU-5, Topol, and Topaz. A thermionic reactor, which has no moving parts, converts heat directly into electricity through the process of thermionic emission, the spontaneous ejection of electrons from a surface. The Plazma-A satellites operated in safer 800-kilometer orbits. One of the experimental payloads (called Epikur) was intended to produce plasma clouds making it possible to mask satellites from anti-satellite interceptors.[1] This was part of a much broader effort undertaken by the Soviet Union to protect its satellite fleet from ASAT attacks.[2]

The Soviet-era US-A/RORSAT (left) and Plazma-A satellites. Source |

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, work on space-based nuclear reactors came to a virtual standstill and several were even sold to the US.[3] KB Arsenal turned its attention to a project called Liana, comprising electronic intelligence satellites known as Lotos-S and military radar observation satellites called Pion-NKS. These are solar-powered satellites that share a common bus. After numerous delays the first Lotos-S satellite was orbited in 2009 and it was followed by three more in 2014, 2017, and 2018. Pion-NKS is still awaiting its first mission.

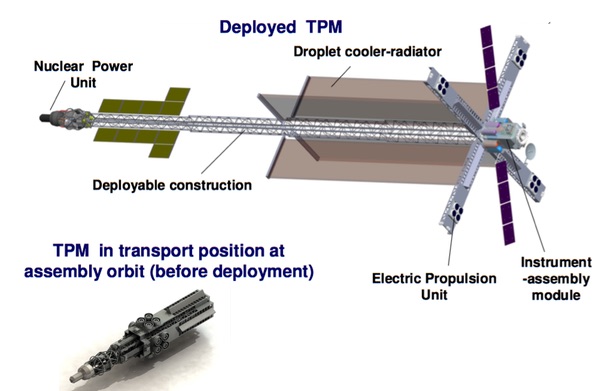

On February 2, 1998, the Russian government adopted a decree aimed at reviving the dormant Russian space nuclear program. It called for resuming research and development in the field with the goal of producing nuclear reactors with a capacity of up to 100 kilowatts and an operational lifetime of five to seven years after 2010. A key short-term goal was to use nuclear reactors as part of so-called “transport and energy modules” (TEM), a Russian term for electric space tugs. The nuclear reactor would power an electric propulsion system to boost spacecraft to their operational orbits (“transport”) and subsequently provide power to their on-board systems (“energy”). This would make it possible to increase the mass of payloads delivered to high orbits by two to three times and supply them with 10 to 20 times more power than before.[4]

In a way, KB Arsenal had already pioneered the transport function with the Plazma-A satellites in 1987. Their nuclear reactors powered small electric thrusters (called 62E or Gryada, built by OKB Fakel) to perform orbital corrections. However, it was not until 2004, six years after the 1998 government decree, that the company got down to designing a real nuclear-powered space tug that could host a variety of payloads. Called Plazma-2010 or UKP-YaEU (an acronym meaning “Universal Space Platform – Nuclear Power Unit”), it was described in some detail in several articles published by KB Arsenal early this decade.[5]

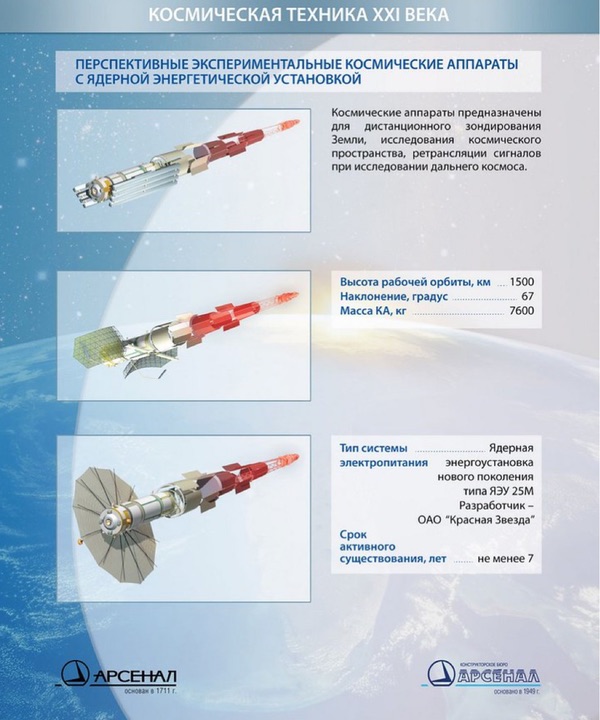

| In 2014, KB Arsenal published drawings of three nuclear-powered satellites on its website that were clearly based on the Plazma-2010 platform. These were literally said to be intended for “Earth remote sensing, space studies and the relay of signals during research of deep space.” |

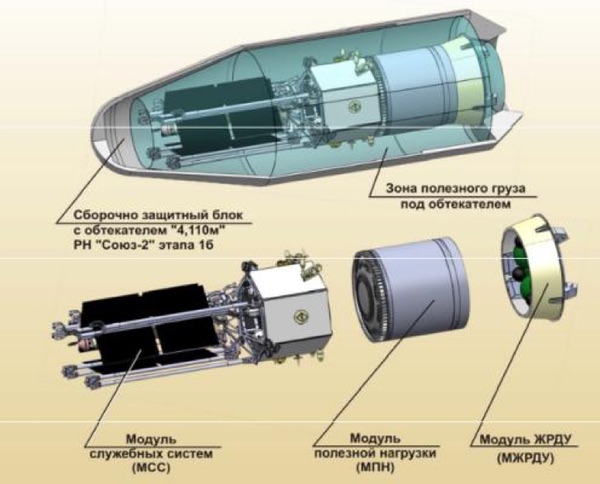

Drawings published at the time showed the platform in its launch configuration attached to a payload and a liquid-fuel propulsion system. After launch, a boom would be extended to place the nuclear reactor at a safe distance from the payload. The platform would carry second-generation thermionic reactors of the Krasnaya Zvezda company, much improved versions of the earlier TEU-5/Topol/Topaz reactor flown in the 1980s. Krasnaya Zvezda worked out plans for several such reactors ranging in capacity from 10 to 400 kilowatts. The lightest of these (YaEU-25M) would make it possible to build a satellite that remained within the launch capacity of a Soyuz-2 class rocket. The heavier ones would require the use of a Proton or Angara-A5 rocket.

The electric propulsion system (not seen in the drawings) would be used to place the satellite into its operational orbit and perform subsequent orbital corrections. Two of the articles said KB Arsenal had ordered the Keldysh Research Center to perform studies of stationary plasma thrusters (a type of Hall-effect thruster) with a capacity of up to 35 kilowatts. No explanation was given for the presence of the liquid-fuel propulsion system. Possibly, it would have to boost the satellite to a relatively high parking orbit before handing over to the nuclear-powered electric propulsion system. In this way, the nuclear reactor does not pose an immediate threat to Earth in case something goes wrong after its activation.

Plazma-2010 platform in its launch configuration on a Soyuz-2-1b launch vehicle. The three main components are the bus with the nuclear reactor (left), the payload (center) and a liquid-fuel propulsion system (right). Source |

In several interviews in 2014, KB Arsenal director general Andrei Romanov underlined that Plazma-2010 was still an active project and that the platform was essentially ready for production.[6] Romanov, who successfully defended a PhD dissertation on satellites with thermionic reactors in December 2013, seems to have strongly promoted the project after becoming KB Arsenal’s director general earlier that same year, but he was replaced by the end of 2014.

In 2014, KB Arsenal published drawings of three nuclear-powered satellites on its website that were clearly based on the Plazma-2010 platform. These were literally said to be intended for “Earth remote sensing, space studies and the relay of signals during research of deep space.” The nuclear reactor was identified as Krasnaya Zvezda’s YaEU-25M and the expected lifetime of the satellites was given as “at least seven years.” The altitude and inclination of the operational orbit were given as 1,500 kilometers and 67 degrees, and the mass as 7,600 kilograms, but it was not clear if this was related to all three satellites or just the one seen in the center (which seems to carry a radar).[7]

Page from KB Arsenal’s former website showing three satellites based on the Plazma-2010 platform. |

Little was heard of Plazma-2010 the following years and there were no signs that it had moved beyond the proposal stage and received government funding. Early this year all information on the platform and the thermionic reactors suddenly vanished from the websites of KB Arsenal and Krasnaya Zvezda. The changes on the two websites did not go unnoticed in the Russian press and raised questions about the status of the project.[8]

In his interviews in 2014 Romanov also disclosed that KB Arsenal had become involved in another space nuclear power project that had been announced by President Dmitri Medvedev in 2009 and officially got underway in 2010. Jointly managed by Roscosmos and the Rosatom State Atomic Energy Corporation, it envisages the development of a one-megawatt gas-cooled reactor with gas-turbine energy conversion to provide power to an array of ion thrusters needed to deliver payloads to high orbits or other destinations in the solar system. It was widely advocated as a propulsion system needed to send Russian cosmonauts to the Moon and Mars. The project is usually referred to as TEM, although, as explained above, this is also a generic term for electric space tugs. The original goal was to begin test flights of the reactor in 2018.

The one-megawatt TEM as proposed in 2010. Source |

Despite its earlier experience with nuclear-powered satellites, KB Arsenal had not been invited to take part in the TEM project from the outset. The major players originally assigned to the project under Roscosmos were the Keldysh Research Center (prime contractor and responsible, among other things, for the development of the ion engines) and RKK Energiya (for spacecraft integration.) The nuclear reactor, which is fundamentally different from the thermionic reactors of Krasnaya Zvezda, is being built by the Dollezhal Scientific Research and Design Institute of Energy Technologies (NIKIET) under Rosatom.

| The one-megawatt TEM project appears to have been affected by the significant budget cuts that hit Russia’s Federal Space Program for 2016–2025. |

There is conflicting information on the exact role of KB Arsenal in the one-megawatt TEM project. In some of his interviews in 2014, Romanov said his company had taken over as prime contractor from the Keldysh Research Center. One court document related to the TEM project indeed says that Roscosmos issued an order on September 29, 2014, to transfer that role to KB Arsenal.[9] However, this is contradicted by procurement documents that show that the Keldysh Research Center was awarded a contract by Roscosmos on June 29, 2016, for work on the TEM project in 2016–2018 and that KB Arsenal subsequently signed a contract with the Keldysh Research Center on November 18, 2016, as a subcontractor.[10] Therefore, it looks like the Keldysh Research Center has retained the role of prime contractor and KB Arsenal merely took over the spacecraft integration role from RKK Energiya, which seems to have abandoned the project at an early stage.

Court documents also reveal that KB Arsenal signed a contract (called TEM-Arsenal) with the Khrunichev Center on July 1, 2015, for work on an orbital demonstrator identified as 327AN30-TEM-1 to be launched by the Angara-A5 rocket. According to the documentation, KB Arsenal initially studied a 140-kilowatt version of the demonstrator, but in May 2016 was ordered to upgrade this capacity to 500 kilowatts, one resulting problem being that it exceeded the launch capacity of the Angara-A5 by about 1.5 tons.[11] Roscosmos chief Dmitri Rogozin recently said that it has not yet been decided if it is necessary to build a 500-kilowatt interim version before moving on to the one-megwatt version.[12] What likely is a model of the demonstrator satellite was shown at the MAKS-2019 aerospace show held this August near Moscow.

Demonstrator for the 1-megawatt TEM reactor on display at the MAKS-2019 aerospace show. Source |

The one-megawatt TEM project appears to have been affected by the significant budget cuts that hit Russia’s Federal Space Program for 2016–2025, approved in March 2016. At that point, Roscosmos ordered a series of studies that would have resulted in the launch of a demonstrator satellite no sooner than 2025.[13] KB Arsenal was assigned to one of those studies (called “Yadro” or “Core”) in November 2017. This was aimed at defining possible missions for TEM by November 2018 and would have to result in determining technical specifications for actual flight vehicles (with a reactor capacity ranging from 100 kilowatts to one megawatt) to be developed under a follow-on effort called Nuklon.[14] An indication that the full-scale one-megawatt TEM may not fly for at least another decade came in a recently released Roscosmos tender, which calls for completing ground-based infrastructure for TEM at the Vostochny Cosmodrome no earlier than 2030, a staggering 20 years after the project was initiated.[15]

Meanwhile, evidence emerged in the past few years for the existence of another KB Arsenal project with the odd name Ekipazh (a French loanword meaning both “crew” and “horse-drawn carriage”). The name first surfaced in the 2015 annual report of a company called NPP KP Kvant, which manufactures optical sensors for satellite orientation systems. It revealed that the company had signed a contract with KB Arsenal under project Ekipazh to deliver an Earth sensor (designated 108M) for “transport and energy modules.” According to the 2015 report, test flights of Ekipazh were to be completed in 2021.[16]

The name Ekipazh also appeared in a PhD dissertation on satellite control systems defended in 2017 by Aleksandr Kulakov, a postgraduate student at a university called the St. Petersburg Institute for Informatics and Automation of the Russian Academy of Sciences (SPIIRAN). Kulakov is attached to SPIIRAN’s Laboratory of Information Technologies in System Analysis and Modeling (LITSAM) and, at the same time, is also is an engineer working for a KB Arsenal department specializing in satellite control systems. Ekipazh is one of several projects in which Kulakov’s research was applied. More specifically, he worked out algorithms making it possible to counter any problems with the satellite’s onboard control system, which can be “automatically reconfigured” in the event of anomalies. Some of the results of Kulakov’s research were also used in a research project to analyze the reliability of a “transport and energy module”.[17]

| While TEM is a civilian project started jointly by Roscosmos and Rosatom in 2010, Ekipazh officially got underway on August 13, 2014, with a contract signed between KB Arsenal and the Ministry of Defense. |

The term “transport and energy module” seemed to imply a link with the one-megawatt reactor, but, as mentioned earlier, it has been used for at least 20 years to refer to electric space tugs in general. The optimistic timelines given for Ekipazh in the 2015 annual report of NPP KP Kvant actually indicated that Ekipazh was a much more realistic project than the futuristic looking one-megawatt TEM.

Documentation published in recent weeks and months on Russia’s publicly accessible government procurement website zakupki.gov.ru has now confirmed that Ekipazh and TEM are indeed separate efforts. While TEM is a civilian project started jointly by Roscosmos and Rosatom in 2010, Ekipazh officially got underway on August 13, 2014, with a contract signed between KB Arsenal and the Ministry of Defense. It has the military index 14F350, an out-of-sequence number in the 14F satellite designation system, pointing to the satellite’s unusual nature.

Three subcontractors to KB Arsenal that can be identified from the documentation are:

This screenshot from Russia’s government procurement website shows part of a draft contract between NIIKP and another company related to the MSSKM-016 system for Ekipazh. It refers to the original contract between KB Arsenal and the Ministry of Defense signed on August 13, 2014 (the contract number can be seen in the last line). Source |

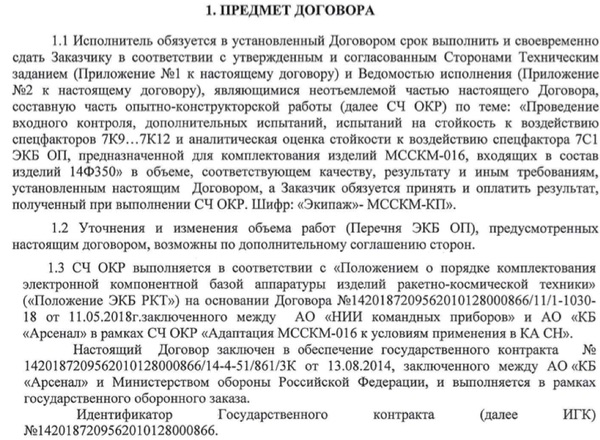

While this procurement documentation reveals little about the true nature of Ekipazh and its “transport and energy module,” contractual information that appeared on the procurement website this summer provides conclusive evidence that Ekipazh is a nuclear-powered satellite and leaves little doubt that it uses the Plazma-2010 platform or an outgrowth of it. It shows that three contracts for the project were recently signed by the Krasnaya Zvezda company, KB Arsenal’s long-standing partner for the production of thermionic nuclear reactors.[21] The actual contracts and related documents are classified, but the contract numbers are clearly based on that of the initial contract for Ekipazh signed between KB Arsenal and the Ministry of Defense on August 13, 2014. They have exactly the same sequence of numbers as the August 2014 contract, followed by a slash and another sequence of numbers denoting the specific contract.

These screenshots from Russia’s government procurement website prove that three contracts recently signed by Krasnaya Zvezda are related to Ekipazh. The initial 25-digit number is identical to that seen in the contract for Ekipazh signed between the Ministry of Defense and KB Arsenal in August 2014. There is a mistake in the first contract number, where the 13th digit should be “2” rather than “1”. |

All that is revealed about the subject of the three contracts (signed on May 20, June 3, and June 28, 2019) is that they were for work on a “conversion reactor” and a “radiation safety system” as well as for an “automatic control system” and “electricity generating channels” for something identified only as “Product 295.” All these are terms often seen in technical literature on thermionic conversion reactors. “Electricity generating channel” is a term specifically used for the fuel elements of a thermionic reactor.

The subcontractors picked for the three contracts were respectively the Leipunskiy Institute of Physics and Power Engineering (GNTs RF – FEI), the All-Russian Scientific Research Institute of Experimental Physics (RFYaTs VNIIEF) and NII NPO Luch, three organizations belonging to Rosatom. The Leipunskiy Institute has a Department of Space Power Systems that works on space-based thermionic reactors and even uses a drawing of a Plazma-2010 type platform as the background for its website.[22] NII NPO Luch’s website says it is currently developing fuel elements for “space-based and sea-based thermionic nuclear reactors”.[23] All these snippets of information strongly indicate that “Product 295” is the code name for a thermionic nuclear reactor that Krasnaya Zvezda is building for Ekipazh.

The specific thermionic reactor under development for Ekipazh cannot be determined with certainty, but the most likely candidate is the YaEU-25M, which was given as the nuclear reactor for the Plazma-2010 platform on KB Arsenal’s website until early this year. This is the lightest of Krasnaya Zvezda’s thermionic reactors and should allow the satellite to be launched by a Soyuz-2 class rocket. However, a PhD dissertation related to second-generation thermionic reactors that was defended in 2016 by a specialist of the Leipunskiy Institute mentions only the YaEU-25 and YaEU-50 reactors, saying the first had reached the “draft plan” phase.[24] These are heavier reactors that would require launch by the Angara-A5 rocket. Data for the YaEU-25M, YaEU-25, and YaEU-50 reactors are given in the table. The reactors can work both in a “nominal mode” (for power supply to the payload and various spacecraft systems) and “peak mode” (for power supply to the electric propulsion system).

| Reactor | YaEU-25M | YaEU-25 | YaEU-50 |

|---|---|---|---|

| power output (nominal mode) (kW) | 10 | 25 | 50 |

| power output (peak mode) (kW) | 35 | 65-87 | 100 |

| fuel | uranium-235 | uranium-235 | uranium-235 |

| fuel mass (kg) | 32.5 | 38.5 | 51 |

| reactor mass (kg) | 1820 | 3000 | 4200 |

| reactor unit dimensions (in launch configuration) diameter (m)/length (m) | 3.0/4.1 | 3.3/3.6 | 3.7/4.0 |

| coolant | sodium-potassium alloy (NaK) | sodium-potassium alloy (NaK) | sodium-potassium alloy (NaK) |

| maximum coolant temperature (K) | 873 | 873 | 873 |

| neutron spectrum | intermediate | intermediate | intermediate |

Data for Krasnaya Zvezda’s YeU-25M, YeU-25 and YeU-50 reactors. Source

| At first sight, the presence of a solar power system on a nuclear-powered satellite does not make sense. |

One possible sign that Ekipazh has evolved from the original Plazma-2010 design is that one of the subcontractors to KB Arsenal in the project is PAO Saturn, an organization based in Krasnodar that specializes in the production of solar panels and storage batteries. This is known from a presentation given by PAO Saturn at a conference in Moscow last February. The PowerPoint version of that presentation was somehow allowed to be placed online despite the fact that it contains the names of several highly sensitive military space projects, including Ekipazh.[25]

At first sight, the presence of a solar power system on a nuclear-powered satellite does not make sense. However, a possible explanation for PAO Saturn’s involvement in the project can be found in a set of safety regulations for nuclear-powered satellites that was approved in October 2017 by Russia’s Federal Service for Ecological, Technological, and Nuclear Supervision (Rostekhnadzor). One of the safety features that such satellites should have is described in the document as an “autonomous power source” which, regardless of the condition of the nuclear reactor, must ensure the functioning of “safety systems, a system to control the parameters determining the safe operation of the nuclear-powered spacecraft and the system to communicate with the on-board control complex and the ground control complex.”[26] The regulations do not seem to pertain specifically to satellites with thermionic reactors, but Krasnaya Zvezda is known to have reviewed a draft version of the regulations.[27] An autonomous power source was also included as a mandatory safety feature in technical specifications for the one-megawatt TEM drawn up in 2010.[28] All this could mean that PAO Saturn is developing some type of backup power supply system for Ekipazh, even though this would complicate the design of the satellite and make it heavier than the originally proposed Plazma-2010 platform.

At this point it is not known what kind of electric propulsion system is under development for Ekipazh. As mentioned earlier, the Keldysh Research Center studied 35-kilowatt stationary plasma thrusters for the Plazma-2010 platform early this decade, but there are no indications that these studies ever moved beyond the drawing board. The Keldysh Research Center did develop 35-kilowatt ion engines (called ID-500) for the one-megawatt TEM project that seem to have reached an advanced stage of testing. However, there is nothing to suggest that these have somehow been made compatible with the TEM for Ekipazh.

All that the available procurement documentation reveals about the objectives of Ekipazh is that it is a “special purpose” satellite (“special purpose” being a commonly used Russian euphemism for “military.”) It can also be inferred from the documents that the program will see more than one launch. What remains uncertain is if Ekipazh is the name of a platform that can carry a variety of payloads or the name of a satellite that will be used for one specific mission. All that can be said for sure is that there must be at least one type of payload that the Ministry of Defense considered important enough to order the design of a nuclear-powered satellite.

The justification for the use of nuclear reactors on the Soviet-era US-A/RORSAT satellites was the presence of a power-hungry radar needed for ocean reconnaissance. KB Arsenal has also advertised radar imaging of the Earth as a possible mission for the Plazma-2010 platform, but Russia currently has several solar-powered civilian and military radar satellites under development (Kondor-FKA(M), Obzor-R, Pion-NKS, Araks-R) that most likely will satisfy the country’s needs for space-based radar imagery of the Earth for many years to come. Therefore, Ekipazh is likely to carry a different kind of payload.

One military mission for Plazma-2010 that KB Arsenal is known to have considered is to perform space-based electronic warfare (EW). KB Arsenal’s director general Andrei Romanov hinted at the company’s interest in such a mission in late 2014, when he said that it was focusing on space-based “armament systems” that would meet the demands of “future warfare.” He also said that those plans had received full support from Dmitri Rogozin, who at the time was the deputy prime minister overseeing the defense and space industries.[29]

| Electronic warfare is also one of the missions studied by KB Arsenal for the one-megawatt TEM project under the previously mentioned Yadro research program in 2017–2018. |

KB Arsenal outlined plans for nuclear-powered EW satellites in several editions of an annual publication called “Electronic Warfare in the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation”, a compilation of articles by military officials and companies involved in Russia’s electronic warfare program. Only a selection of these articles is placed online and this does not include the KB Arsenal articles.[30] However, full PDF versions of the 2014 and 2015 editions did circulate online for a while and details of KB Arsenal’s contribution to the 2016 edition appeared in the newspaper Izvestiya in August 2016.[31]

While not going into too much detail, the articles acknowledged that Plazma-2010 had been designed with the possibility of installing EW payloads. The presence of a nuclear reactor would make it possible to install “jammers operating in a wide range of frequencies” and place such payloads into highly elliptical and geostationary orbits for “uninterrupted suppression of electronic systems in large areas.” The spacecraft would be delivered to their operational orbits by an electric propulsion unit and are therefore referred to in the articles as “transport and energy modules.” The EW mission would require a reactor generating at least 30 to 40 kilowatts, allowing the satellites to be launched by the Soyuz-2-1b rocket. For more advanced EW missions, the performance would have to be increased to 100 kilowatts, necessitating a switch to the more powerful Angara-A5 rocket. The 2016 article (as quoted by Izvestiya) said KB Arsenal was working on two types of reactors with a capacity of 30 and 50 kilowatts respectively. It was also noted that satellites flown under KB Arsenal’s Liana program could provide intelligence in support of the EW mission. It would even be possible to adapt the solar-powered Liana bus for a “more limited” electronic warfare mission requiring less power.

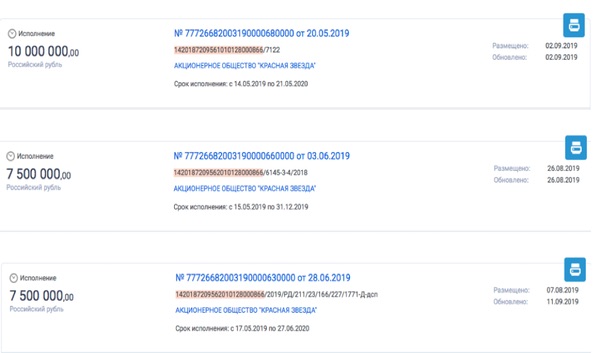

The articles mention the need to use large-size antennas for the EW mission and one of them describes two possible configurations for the payload, one with the antenna mounted perpendicularly to the longitudinal axis of the satellite and the other with the antenna installed along the axis of the satellite. Interestingly, the EW satellites depicted in the articles look identical or very similar to the Plazma-2010 satellites seen on KB Arsenal’s website until early this year.

KB Arsenal drawing of a nuclear-powered EW satellite. |

According to one of the articles, the deployment of EW platforms in orbit would be in accordance with a policy for Russia’s electronic warfare program until 2020 approved by the Russian government in January 2012. A summary of this policy indeed mentions space-based electronic warfare as one of the objectives to be accomplished in the period before 2025. More specifically, it talks about the need to deploy “multifunctional space-based EW complexes for reconnaissance and suppression of radio-electronic systems used by radar, navigation and communications systems.”[32]

Asked about these plans by Izvestiya in August 2016, KB Arsenal’s director general Aleksandr Milkovski told the newspaper that “if the military is interested in Arsenal’s proposal, the company is prepared to implement this project.” That would suggest the company had not yet received an order for such a payload at the time, but if it had, Milkovski may not have wanted to acknowledge that. The newspaper also quoted an anonymous source in Russia’s “military-industrial complex” as saying that “a KB Arsenal satellite with a nuclear reactor” could be placed into orbit before 2020, something which Milkovski was not willing to confirm. Most likely, this was a reference to Ekipazh.

Electronic warfare is also one of the missions studied by KB Arsenal for the one-megawatt TEM project under the previously mentioned Yadro research program in 2017–2018. As is known from the tender documentation released for Yadro, Roscosmos ordered participants in the tender to look at EW payloads capable of interfering with “control, intelligence, communications and navigation systems.” KB Arsenal proposed an EW payload with a maximum mass of five tons and a power source generating between 100 and 1,000 kilowatts. The dimensions of the EW antenna were given as 10 x 2.5 x 0.4 meters in “transport mode.” The only other missions in Roscosmos’ specifications for Yadro were remote sensing, directed energy transfer using lasers, communications, and interorbital transport of payloads.[33] The solar system missions widely advertised for the one-megawatt TEM in the early years of the project were notably absent from the objectives.

All this, along with the fact that the one-megawatt TEM project has become increasingly cloaked in secrecy in recent years, is a possible sign that it is being at least partially militarized. It is worth noting in this respect that training sessions on handling hazardous radioactive materials that were organized last year for both Roscosmos and KB Arsenal specialists were described as being related to the use of “nuclear energy for defense purposes.”[34]

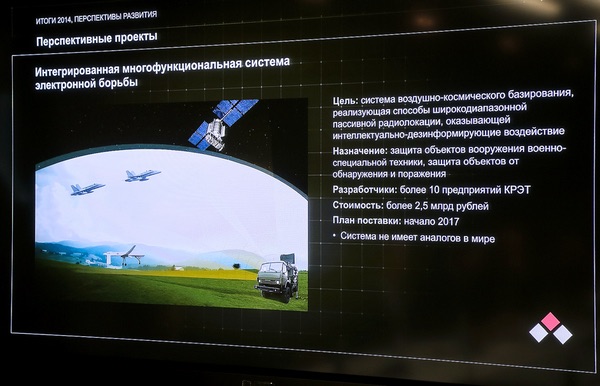

As of now there is no solid evidence linking Ekipazh to an electronic warfare mission, but there are indications that a space-based EW system was approved around the same time that the Ministry of Defense gave the go-ahead for Ekipazh. The existence of a space-based EW program was acknowledged several years ago by Igor Nasenkov, the deputy general director of KRET (Concern Radio-Electronic Technologies), the largest holding in Russia’s radio-electronic industry. It was formally established in 2009 through the merger of various companies under the Rostec State Corporation and incorporates some of the country’s leading manufacturers of electronic warfare systems. In several interviews in early 2015, Nasenkov talked about an “integrated multifunctional airborne and space-based electronic warfare system” designed to “protect military technology from detection and destruction,” but also “to knock out and suppress the enemy’s radio-electronic systems.” It would include “wide-band passive radars” capable of covertly obtaining intelligence on enemy assets and would be targeted at enemy reconnaissance, navigation, communications, data relay and weapon control systems through the use of what Nasenkov called “force and intellectual disinformation.”

KRET slide showing an air and space-based “integrated multifunctional electronic warfare system”. The satellite depicted here is a Glonass navigation satellite, which has no apparent connection to the system. Source |

Nasenkov said the system was seen as an “asymmetrical response” to the development of new American “airborne and space-based combat systems” as well as the deployment of a US anti-missile system in Europe, stressing that it is unrivaled in the world. He called the space-based component of the system “classified,” admitting only that KRET was working on “specialized on-board equipment for a future electronic warfare satellite.”[35] A similar statement was made by a KRET representative at the Aero India 2015 airshow in Bangalore in February 2015.[36] Available information indicates that work on the integrated EW system got underway in 2013–2014, which coincides with the start date for Ekipazh in August 2014. According to the information provided in early 2015, the first elements of the system were expected to be fielded in early 2017, but that likely relates only to some of the air-based components.

| Despite the safety risks associated with launching nuclear reactors into space, there are no international rules forbidding nations from doing so. |

Nasenkov’s vague description of the integrated EW system covers all three aspects of electronic warfare, namely electronic attack (the offensive use of electromagnetic energy against the enemy’s combat capability), electronic protection (the defense against the enemy’s electronic attack systems), and electronic warfare support (the gathering of intelligence on the enemy’s radio-electronic systems.) It is hard to say what exactly the role of the space-based component is. Assuming that the EW satellite is indeed Ekipazh, the most plausible objective would be electronic attack, the only of the three that would seem to require the amount of energy warranting the use of a nuclear power source. However, a combination of the various functions is also possible.

It is also unclear whether the space-based EW component will be aimed at targets in space, on the ground or both. It should be noted that Russia already has or is developing ground-based systems for both signals intelligence of foreign satellites (Moment, Sledopyt) and electronic warfare against foreign satellites (Krasukha-4, Divnomorye, Tirada-2S).

According to Nasenkov, more than ten companies within the KRET holding were engaged in the development of the integrated electronic warfare system. At least three companies under KRET which work on EW projects have earlier experience with space-based systems, namely the Kaluga Scientific Research Institute of Radio Engineering (KNIRTI), Fazotron-NIIR and the Berdsk Electromechanical Plant (BEMZ). KNIRTI built payloads for KB Arsenal’s Soviet-era electronic ocean reconnaissance satellites (US-P), solar-powered satellites that complemented the data provided by the nuclear-powered US-A satellites.

Another potential industrial partner for a space-based EW payload would be the Central Scientific Research Institute of Radio Engineering (TsNIRTI), which has had a long monopoly in building payloads for KB Arsenal’s electronic intelligence satellites and also develops ground-based and airborne electronic warfare systems (KNIRTI was a branch of this organization until it became independent in 1991). TsNIRTI officials have talked about the need to integrate ground, air, sea and space-based electronic warfare systems.[37] However, TsNIRTI is not part of KRET, but of another concern called Almaz-Antei.

Despite the safety risks associated with launching nuclear reactors into space, there are no international rules forbidding nations from doing so. In September 1992, the General Assembly of the United Nations did adopt the so-called “Principles Relevant to the Use of Nuclear Power Sources in Outer Space,” but these do not have the same binding force as the UN Outer Space Treaties.

One of the Principles stipulates that nuclear reactors may be operated on interplanetary missions, orbits high enough to allow for a sufficient decay of the fission products, or in low-Earth orbits if they are boosted to sufficiently high orbits after the operational part of the mission. As explained earlier, the latter procedure was followed for the Soviet-era RORSAT missions, but it is highly unlikely that Russia would want to risk repeating the Cosmos 954 experience of 1978. In fact, the very presence of a “transport and energy module” on Ekipazh is a sure sign that it will be placed into an orbit high enough to prevent any harm. Before the nuclear-powered TEM is even activated, a liquid-fuel propulsion system may first boost the satellite to an orbital altitude of at least 800 kilometers, the same procedure that has been described for the one-megawatt TEM. During a recent question-and-answer question with students in St. Petersburg, Roscosmos chief Dmitri Rogozin confirmed that 800 kilometers is the minimum operating altitude for nuclear reactors. Judging from Russian press reports, Rogozin was actually replying to a question about Ekipazh, but seemingly dodged that by talking about the one-megawatt reactor instead.[38]

Another Principle states that launching nations should make a thorough and comprehensive safety assessment and share the results of that with other nations before launch:

The results of this safety assessment, together with, to the extent feasible, an indication of the approximate intended time-frame of the launch, shall be made publicly available prior to each launch and the Secretary-General of the United Nations shall be informed on how States may obtain such results of the safety assessment as soon as possible prior to each launch.

Russia adhered to this rule on the only occasion that it launched nuclear material into space after the adoption of the 1992 Principles. This was on the ill-fated Mars-96 interplanetary mission, which carried two surface penetrators powered by small radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs). However, unlike Ekipazh, Mars-96 was an international scientific mission and the presence of the RTGs was widely known. It will be interesting to see how Russia deals with this issue once the top-secret Ekipazh nears launch.

It may well be several more years before that launch takes place. Although the initial goal appears to have been to finish test flights by 2021, the available procurement documentation suggests that the first mission is still some time off. Ekipazh may well be experiencing the same kind of delays suffered by many other Russian space projects due to both budgetary issues and Western-imposed sanctions that have complicated the supply of electronic components for space hardware. On top of that, the development of a nuclear-powered satellite is bound to pose some daunting technical challenges that may further contribute to the delays.

| Ekipazh could serve as a testbed for all the nuclear reactors that Russia intends to fly in the near future. |

One also wonders if the Russians are biting off more than they can chew by simultaneously working on two nuclear electric space tugs (Ekipazh and the one-megawatt TEM). An attempt to streamline this effort seems to have been made by giving KB Arsenal a leading role in both projects in 2014, making it possible to benefit from the company’s earlier experience in the field and infrastructure that it may already have in place to test related hardware. Still, the two projects use fundamentally different nuclear reactors built by different organizations.

The slow progress made in developing the one-megawatt gas-turbine reactor has left many wondering if it will ever fly in space. If Russia plans to use nuclear reactors solely for practical applications in Earth orbit, it may make more sense to abandon the gas-turbine reactor altogether and upgrade the capacity of Krasnaya Zvezda’s thermionic reactors. The company has already done conceptual work on thermionic reactors with a maximum capacity of several hundred kilowatts, even though their operational lifetime would be limited.[39] If this path is chosen, Ekipazh could serve as a testbed for all the nuclear reactors that Russia intends to fly in the near future. However, the country is unlikely to let all the money and effort invested in the one-megawatt TEM go to waste, even if its capabilities may not be needed until well into the 2030s or even later.

Project Ekipazh is discussed in this thread on the NASA Spaceflight Forum, which is updated with new information as it becomes available.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.