What to do with that olde space stationby Eric Choi

|

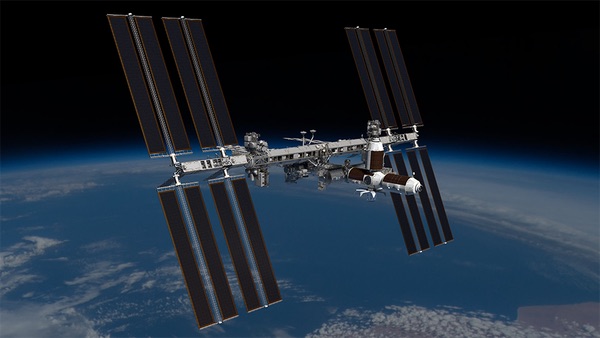

| The International Space Station will be the largest human-made object ever brought down to Earth, and doing so safely will be a challenging engineering problem. |

Last November, the International Space Station (ISS) celebrated 20 years of continuous human occupation. Later this year, Russia intends to launch later this year the Nauka multipurpose laboratory module to the ISS, followed next year by the launch of a five-port docking node called Prichal that will be attached to the nadir (Earth-facing) side of Nauka. NASA has awarded an initial contract to a private US company, Axiom Space, to provide up to three new commercial modules to be attached to the ISS, the first of which is scheduled for launch in 2024. The current multinational ISS partnership, consisting of the United States, Russia, the European Space Agency, Japan, and Canada, is discussing the extension of ISS operations to 2028 or 2030 and perhaps even longer, but like its fictional counterpart on Babylon 5, at some point its mission will end and the station will have to be removed from orbit.

The International Space Station will be the largest human-made object ever brought down to Earth, and doing so safely will be a challenging engineering problem. Nobody wants a repeat of the (mostly) uncontrolled reentry in 1979 of the first US space station, Skylab, parts of which ended up hitting a remote region of Australia and resulting in a $400 littering fine to NASA.

One of the cargo vehicles that brings supplies to the ISS is called Progress, a type of spacecraft the Russians have been using since the late 1970s to support their earlier generations of space stations. The current ISS decommissioning plan envisions using a modified Progress equipped with a more powerful engine, extra propellant tanks, and the plumbing needed to use up any remaining fuel in the Russian segment of the ISS. This modified Progress would execute a series of high-thrust burns to lower the ISS orbit and eventually bring the station to a fiery destructive plunge into a remote part of the ocean—likely the South Pacific or the Indian Ocean—as far away from major shipping lanes as possible (see “menace to navigation.”)

Such was also the fate of the immediate predecessor to the ISS, the much-maligned Russian space station Mir. For a brief time, the Mir actually got a temporary stay of execution. In 2000, a private firm called MirCorp signed an agreement with the Russian space company RSC Energia to lease the station for commercial activities. MirCorp privately funded a 73-day mission to Mir by two cosmonauts later that year, which turned out to be the final expedition. Plans to refurbish the station and raise its orbit were not realized, and the Russians eventually succumbed to political pressure to decommission the Mir and concentrate its resources on the ISS. The fascinating saga of MirCorp is chronicled in the documentary Orphans of Apollo.

Prior to the deorbiting of the ISS, Axiom intends to detach its modules as the basis of a new commercial space station. At one time, the Russians had considered detaching Nauka and Prichal with some of their older modules to create an independent space station called OPSEK, but these plans were cancelled in 2017. One of the most innovative ideas for repurposing ISS modules came out of a report called Metztli (named after the Aztec lunar goddess) written by students at the International Space University that proposed sending the ISS or some of its components towards lunar space using an Earth-Moon cycling orbit.

| Such linkages between science fiction and our real-life exploration of space are a big part of what appeals to me about the sci-fi/fantasy genre. |

Both the Americans and the Russians have experience in successfully repairing crippled space stations. Six years before dropping in on the Australian outback, Skylab suffered significant damage during its launch in 1973. As a result of the mishap, a micrometeoroid shield separated from the hull and tore away, taking one of two main solar panels with it and jamming the other panel so that it could not deploy. The first Skylab crew of astronauts Pete Conrad, Joe Kerwin, and Paul Weitz succeeded in installing a Sun shield over the damaged hull and releasing the stuck solar array. Equally remarkable was the courage of Russian cosmonauts Vladimir Dzhanibekov and Viktor Savinykh, who in 1985 endured almost two weeks of cold, darkness, and physical hardship to bring the Salyut 7 station back to life after a power system failure left it dead in space. A Russian film dramatizing the rescue of Salyut 7 was released in 2017.

Shortly after the launch of the first elements of the International Space Station in 1998, I remember reading an online post by Babylon 5 creator J. Michael Straczynski in which he commented on the outward physical resemblance between his fictional station and the Zvezda service module of the ISS. Such linkages between science fiction and our real-life exploration of space are a big part of what appeals to me about the sci-fi/fantasy genre. Historian Roger Launius has called space stations “base camps to the stars”, and I cannot help but agree. Now, if only the Centauri would actually sell us jumpgate technology, then we’d really be getting somewhere.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.