Should India join China and Russia’s Lunar Research Station?by Ajey Lele

|

| Developing multilateral mechanisms for undertaking major projects in the space domain is not a new idea. |

NASA’s Artemis Accords and the China-Russia proposal to build a Lunar Research Station are two recent programs that are expected to impact the long-term vision of humans on the Moon. History demonstrates that reaching the Moon is not only about the demonstration of technological dominance as well a the larger geopolitical logic associated behind it. New projects for the Moon also need study regarding any the possible influence of these projects on the future of space security. These projects offer an opportunity to start (or restart) a debate about the need for the development of a rule-based mechanism for the management of planetary resources.

Developing multilateral mechanisms for undertaking major projects in the space domain is not a new idea. In the post-Cold War period, one of the most successful space collaboration initiatives has been the construction of International Space Station. This effort has, so far, managed two decades of continuous human presence in space. NASA’s Artemis program is a multilateral mechanism for going to the Moon and beyond; while the China-Russia Lunar Research Station is currently a bilateral mechanism, they are keen to have more partners associated with it.

NASA’s Artemis program is about returning humans to the Moon, and going beyond, with commercial and international partners. Apart from the US and South Korea, the member states that have joined the Artemis Accords include Australia, Canada, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and Ukraine. (As this article was being prepared for publication, New Zealand announced it had signed the Accords.) The first major step in this program would be to undertake the landing of humans on the Moon as soon as 2024.

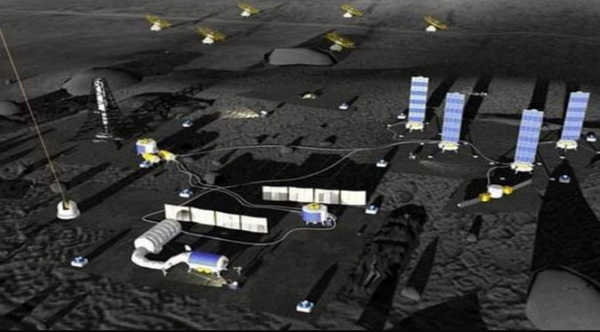

The second project involves proposals by China and Russia to build a Lunar Research Station, either on the Moon’s surface or in lunar orbit. The idea is to develop this station as a scientific base with the capability for conducting long-term autonomous operations, where lunar-based observations and various scientific experimentations would be undertaken. China and Russia have not yet announced any definitive timeline for this project, which still appears to be at its earliest phases.

| Today in the space domain there are two competing blocs. One consists of the US and it allies, and the other is Russia and China. They oppose almost each other’s every idea in regards to space security. |

Countries like the US, Russia, and China have very successful space programs and have undertaken major investments in the space arena over the years. They have their individual programs for the Moon (and Mars) and have achieved some major successes so far. However, perhaps realizing that vast financial and technological sources are required to undertake such programs—not to mention diplomatic reasons—these states have decided to simultaneously undertake collaborative programs too.

Russia is collaborating with the US on the ISS project and the US was also keen to have them join the Artemis program. However, Russia has decided to work with China for exploring the Moon. The US Congress bans almost all contacts between NASA and China. Hence, it is unlikely that the US and China will cooperate for the foreseeable future.

Some signatories to Artemis Accords are also continuing with their own planetary programs. The UAE is undertaking a Moon mission with the assistance of Japan in 2022. Their Hope orbiter for Mars was launched in July 2020 and successfully entered Martian orbit in February. Japan is also planning for a sample return mission to the moons of Mars.

The Artemis Accords specifically acknowledge and reaffirm their commitment to the Outer Space Treaty (OST). However, the Accords appear to be conveniently using the 1967 OST mechanism, particularly in the context of the management of space resources. It is important to note that the US has the cover of their 2015 Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act and, in future, could engage in unilateral exploitation of celestial bodies or could carry it out under the project Artemis. Two signatories to Artemis Accords, Luxembourg and the UAE, have also established a legal architecture at the national level, which permits their space industry to undertake the extraction of minerals from extra-terrestrial bodies.

At present, the extraction of minerals from extraterrestrial bodies is not an issue of immediate concern for many, owing to the absence of technology to undertake any major planetary mining activity. However, this situation is going to change in the future. China’s fifth mission to Moon, Chang’e 5, was a sample-return mission and brought nearly two kilograms of soil and rocks last December. Their next mission to Mars, launching as soon as 2028, would be a sample return mission. Currently, NASA’s Perseverance rover is the process of collecting samples of Martian surface, which would be brought back to Earth by two missions launching no earlier than 2026. Also, Japan’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft returned to Earth in December with samples of the asteroid Ryugu.

China and Russia have yet to spell out the details about their specific proposal to build a Lunar Research Station. Possibly, this is the time for other nations to join this project and ensure that the project develops in a manner that ensures that the planetary system continued to be the common heritage of humanity. It is unlikely that China and Russia would allow other partners to dilute their agenda, but that should not stop other agencies from trying.

Today in the space domain there are two competing blocs. One consists of the US and it allies, and the other is Russia and China. They oppose almost each other’s every idea in regards to space security. They are just not open to any of ideas from the other side. This is harming any possible creation of rule-based mechanisms for conduct of activities in space.

Hence, there is a need for “sensible” space powers to arbitrate directly or indirectly. For example, as part of an effective engagement strategy, states like India could join the Russian-Chinese proposal for a Lunar Research Station. For many years, Russia and India have been collaborating in the space arena, so Russia should have no objection to India joining this project. It is a reality that India and China are geopolitical adversaries. However, in the domain of space they do have some collaborative efforts in place. There are “framework agreements” signed betweer these nations in the initial years of the 21st century, however this agreement lies dormant for many years. In September 2014, a memorandum of understanding was signed between India and China, enabling them to encourage exchange and cooperation in the exploration and use of outer space for research and development of remote sensing, communications, and scientific experiment satellites. Now the Lunar Research Station project offers an opportunity for both nations to bring such paper promises in reality. Actually, it could be in the interest of China to invite India to join their lunar project.

| Nations like India need to take the initiative to ensure fairness in the arena of distribution of planetary resources. |

First, such collaboration could itself help somewhat harmonize the differences between them: maybe not on the ground, but at least in the domain of outer space. It would be naive think that both these ASAT powers would suddenly become space buddies, but such collaboration could help build confidence. Second, China and Russia have long been pushing for their draft treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space. However, there are no takers even for discussing their draft. India, though, is open for negotiating this treaty as a legally binding instrument in the Conference on Disarmament.

Third, India is a part of BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) multilateral mechanism of emerging economies. This multilateral mechanism has arrangements for satellite data sharing. Now, there is an opportunity for India, Brazil, and South Africa to join the Lunar Research Station. However, there is a possibility that Brazil could join the Artemis Accords in near future. Here, China and India need to be more proactive diplomatically and ensure that space remains as an important agenda item for BRICS. Lastly, it is no secret that the US is keen to use (or using) India to counterbalance Chinese influence on Asia. The Lunar Research Program provides an excellent opportunity for China-India engagement.

Nations like India need to take the initiative to ensure fairness in the arena of distribution of planetary resources. The Artemis Accords and the China-Russia Lunar Research Station program clearly indicate that the US and China are interested in space hegemony and are keen to control the management of planetary resources in the future. Such collaborations are likely to ensure that technologically savvy and wealthier states would dominate the process of future rulemaking in the space domain. Criticizing any such possible attempts by sitting on the fence will not help. It is the duty of independent-thinking states to keep in check any such attempts. One way to beat them in this game is to join the game.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.