Wizards redux: revisiting the P-11 signals intelligence satellitesby Dwayne A. Day

|

| The history of the P-11 program is akin to a jigsaw puzzle where a few pieces were dropped on the table over many years, before half the box was emptied out on the table within the past year. |

Starting in 2015, the NRO began declassifying several of its signals intelligence satellite programs in a series of phases. The first phase involved a program known as AFTRACK that placed signals detection payloads on the aft racks of Agena spacecraft launched into low Earth orbit from the late 1950s to 1964. AFTRACK was virtually unknown until the NRO released dozens of documents on the program. It was the space example of a “quick reaction capability” for radar and electronics that the Air Force had developed since the Korean War. The next step, which the NRO referred to as “phase two,” was the 2017 declassification of a series of 16 large satellites known by numerous names and the overarching designation of Program 770. These satellites were launched into low Earth orbit between 1960 and 1972. They carried several payloads and had multiple missions, but a primary mission was the detection and location of air defense radars within the Soviet Union to aid American strategic bomber crews. (See “The wizard war in orbit,” The Space Review, June 20, 2016, Part 1, 2, 3, and 4; “And the sky full of stars: American signals intelligence satellites and the Vietnam War,” The Space Review, February 12, 2018.)

At the time of the phase two declassification, the NRO indicated that phase three of their signals intelligence declassification effort would take place by 2018 and that it would involve the P-11 satellites that essentially took over the duties of the AFTRACK program, flying similar payloads but for many months rather than the few days for AFTRACK. The first P-11 satellites were launched in 1963, and the last in 1992, although the overall program name changed several times, and the satellite configurations changed as well. The NRO also began releasing information on the P-11 satellites themselves, usually in response to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. Initially this included photographs as well as the names and general mission descriptions of many of the satellites. But by late 2020, in response to a FOIA request, the NRO released significant technical details on approximately a quarter of the P-11 programs. Clearly the NRO has determined that much information on the P-11s is releasable, it simply has not yet been released. (See “Little Wizards: Signals intelligence satellites during the Cold War,” The Space Review, August 2, 2021.)

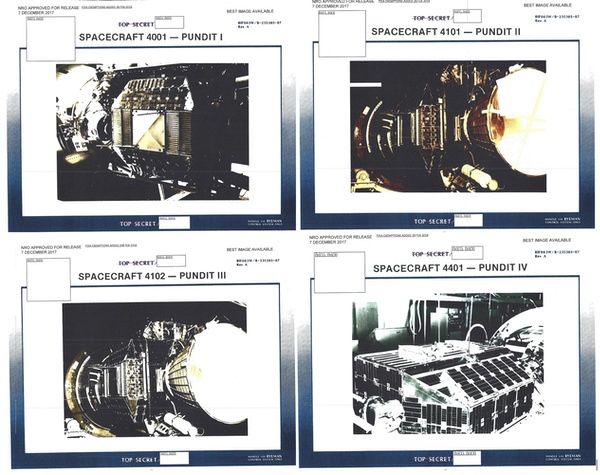

The four PUNDIT satellites were launched between 1963 and 1965, although PUNDIT III did not make it to orbit. PUNDIT may have been designed to gather information from Soviet missile tests. The name was a play on the words "punt it home" about how the satellites would relay their data to a ground station. (credit: NRO) |

The history of the P-11 program is akin to a jigsaw puzzle where a few pieces were dropped on the table over many years, before half the box was emptied out on the table within the past year. It is now possible to understand the overall outlines of the program and many of its details, but the picture is still full of holes.

| The names chosen for various NRO payloads or spacecraft over many years often indicated a wry sense of humor or inside jokes. |

In 2015, Peter Swan and Cathy Swan published the book Birth of Air Force Satellite Reconnaissance that provided some personal accounts of early intelligence satellite programs, including the P-11 satellites. That book dropped a few more puzzle pieces on the table, and in retrospect, it is possible to fit them into the larger picture. Jack Kulpa, who in the latter 1970s rose to the rank of major general in the Air Force and for many years ran SAFSP, the Secretary of the Air Force Special Projects office that was the NRO’s West Coast office, added an anecdote about his early involvement in the P-11 program. “In 1963 I had to go in front of General Greer to try to get a new program approved. After… two and a half hours, I walked away with $2 million… and Program P-11.” Obviously Kulpa played a major role in getting the P-11 program started, but his comment indicates two other interesting facts: when it came to approving programs (at least small ones), the NRO could move with remarkable speed; and Kulpa obviously spent most of his career at the NRO, only leaving SAFSP in 1982. Kulpa’s two-and-a-half-hour pitch meeting resulted in a program that lasted three decades.

But Kulpa’s brief description leaves many questions unanswered. Extending the life of the AFTRACK payloads was a rather obvious evolutionary development. But where did the idea come from? Did it originate with Lockheed Missiles and Space Systems, which built the spacecraft bus for the P-11 satellites? Or did somebody at the Air Force program office within the NRO ask Lockheed to do it? Did Kulpa initiate the idea, or did somebody bring it to him?

Another remaining mystery is what the satellites were designated over time. At some point the designation P-989 (for Program 989) was introduced. But a 1975 document refers to “P-989 vehicles,” “P-989 missions,” and “P-11 satellites,” leaving the impression that although the name may have been formally changed to P-989, those familiar with the satellites kept referring to them as P-11s.

The names chosen for various NRO payloads or spacecraft over many years often indicated a wry sense of humor or inside jokes. As an official NRO history stated, “the early P-989’s were assigned comical names by whoever could think of a good name. Later, SAFSP chose acronyms or women’s names for the satellites.” An example is a series of P-11 satellites launched in the 1960s known as PUNDIT, and apparently designed to intercept telemetry. According to a declassified history, “NSA wanted to transpond the signal and Lockheed suggested recording the information, dumping it, thus calling the payload ‘shove it.’ Both capabilities were provided, thus you SIVET, SHOVE IT, and PUNDIT home.”[1]

The recently declassified trove of documents on the P-11 satellites revealed that many of them recorded their data and then replayed it over a ground station, but some of them had the capability to directly read out their information to a ground station—assuming that they were intercepting signals while in view of a ground station. That capability was one of the characteristics of the Navy’s POPPY signals intelligence satellite program and helped make it adaptable to the ocean surveillance mission by the 1970s. (See “Spybirds: POPPY 8 and the dawn of satellite ocean surveillance,” The Space Review, May 10, 2021; “Shipkillers: from satellite to shooter at sea,” The Space Review, June 28, 2021.)

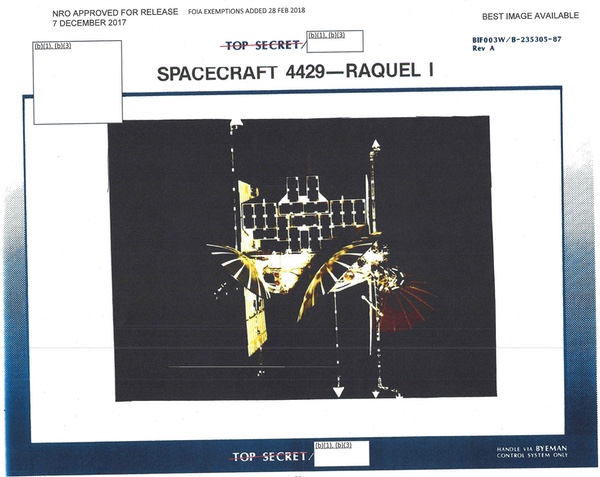

| A later satellite was named RAQUEL, and several satellites launched in the 1980s and early 1990s were known as FARRAH. Obviously, the Air Force officers at the NRO’s West Coast office had an interest in movie stars. |

The newly released documents imply that directly reading out data to a ground station was primarily a backup capability in case of tape recorder failure on a satellite. But in Birth of Satellite Reconnaissance, another former Air Force officer, Don Thursby, recounted how this could also be a way to bring signals intelligence data directly to tactical users, something that the NRO increasingly tried to do in the 1970s:

“In the early 1970s the new mission was to get data directly to the commander on the FEBA (Forward Edge of the Battle Area). I had a payload with possibilities if it could be ‘trailerized’. We decided to go for it, but needed a catchy name, so we used DRACULA.... Direct Readout and Collection ULA (‘ULA’ was the three-letter shorthand for the URSULA payload.) I put a briefing together to take east, but needed to get it through SP-1. General Bradburn liked the briefing but trashed the name, saying that he could already hear the welcome by the East Coast: ‘Oh, no, not another blood sucking program from out west!’” (page 129)

Thursby referred to the URSULA satellite. Several URSULAs flew during the 1970s, apparently named after actress Ursula Andress, who was perhaps most famous for her appearance in the James Bond film Dr. No. However, the satellite was also spelled “URSALA” in NRO documents—sometimes spelled both ways in the same document. It’s a minor inconsistency, but amusing that even classified documents contain spelling errors. A later satellite was named RAQUEL, and several satellites launched in the 1980s and early 1990s were known as FARRAH. Obviously, the Air Force officers at the NRO’s West Coast office had an interest in movie stars.[2]

The RAQUEL satellites were launched in the 1970s and named after Raquel Welch. They were later followed by a series of satellites named FARRAH. One FARRAH satellite was lost when its timer did not turn the satellite on after it was deployed from its Titan II rocket. (credit: NRO) |

The last of the P-11 satellites were launched in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Three satellites designated FARRAH were launched on Titan II rockets, one each in 1988, 1989, and 1992. According to a person who worked on them, these satellites were disk-shaped as opposed to the earlier rectangular pyramid shape of the P-11s. The change in shape was possible because the satellites were designed for launch from the Space Shuttle, not the side of a HEXAGON reconnaissance satellite. The decision to switch to the shuttle occurred in the early 1980s, when the HEXAGON was destined for retirement. Switching to the shuttle required major changes to address shuttle safety demands. One of those requirements apparently resulted in the loss of the second satellite.

| The NRO’s plans for using the Space Shuttle, and their impacts on NRO programs, remains one of the few holes in the history of the shuttle program. |

NASA safety requirements dictated that the satellites had to be inactive while in the shuttle’s payload bay. The satellites therefore operated on a timer that turned them on at a point after their release. The first Titan II launch in 1988 went off without a hitch. But when the second satellite was ejected off its launch vehicle in 1989, something went wrong with the timer. It never turned on and so it never fired its rocket engine. It soon burned up in the atmosphere. According to the person who worked on it, ground controllers tried to jolt it into action by sending a huge amount of energy up to the satellite from a ground transmitter, but to no avail.

The person who was involved in the satellite program explained that a post-mishap investigation uncovered a rather simple explanation for the problem. “They f----- up,” he said: the timer had never been properly modified for the change from the shuttle to the Titan II. The problem should have occurred on the first Titan II launch, but a change in the launch conditions—possibly a launch hold—had resulted in it turning on after deployment. They fixed the problem for the third and final launch.

The NRO’s plans for using the Space Shuttle, and their impacts on NRO programs, remains one of the few holes in the history of the shuttle program. Perhaps we’ll soon learn more about that too.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.