Two directorate heads are better than oneby Jeff Foust

|

| “All this growth has led our Human Exploration and Operation Mission Directorate to grow substantially,” Nelson said. “You need to have the ability of two brilliant people to run the respective responsibilities.” |

Ten years and one month later, NASA effectively undid that change. Last Tuesday, NASA announced it was splitting HEOMD into two separate mission directorates. One, Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate, would be responsible for developing and demonstrating the various elements of the overall Artemis program, including SLS and Orion as well as the Human Landing System, Gateway, and related systems. The other, the Space Operations Mission Directorate, would be responsible for the ISS as well as the agency’s low Earth orbit commercialization strategy. In other words, pretty much the same division as a decade ago, with almost the same names.

“This reorganization is about the future of space exploration,” NASA administrator Bill Nelson said at a town hall meeting. “It’s about setting up NASA for success. Creating two separate mission directorates ensures these critical areas have focused oversight.”

But why now? Nelson suggested HEOMD had become too big to manage as a single organization. “All this growth has led our Human Exploration and Operation Mission Directorate to grow substantially,” he said after discussing various efforts within the directorate, like the upcoming Artemis 1 launch. “Our human spaceflight programs in low Earth orbit and development programs for deep space exploration, all of this accounts for nearly half of NASA’s entire budget.”

He reiterated that in a call with reporters later in the day. “The growth has been so large that, the long and short of it is, the existing or the previous HEO is almost half the budget of NASA,” he said. “You need to have the ability of two brilliant people to run the respective responsibilities.”

However, as a share of NASA’s budget, human spaceflight has not changed much over the last decade. In fiscal year 2012, the first full year of HEOMD, human spaceflight accounted for 44.4% of NASA’s budget. (That’s defined as the combination of the Exploration and Space Operations budget accounts; despite the merger of the two directorates, their budget accounts remained separate.) In fiscal year 2021, human spaceflight accounted for 45.1% of NASA’s budget. In the intervening years, it never grew larger than 47.1%, and never smaller than 44.1%.

What had changed, however, is the absolute funding levels, and the mix between exploration and operations. In 2012, space operations had a budget of nearly $4.2 billion, while exploration got $3.7 billion. In recent years, though, exploration’s budget has grown as SLS, Orion, and ground systems were augmented by HLS, Gateway, and other exploration programs. Operations, which saw an increase during commercial crew development, had declined as that program matured. In 2021, exploration received $6.5 billion and operations just under $4 billion.

Both Nelson and deputy administrator Pam Melroy suggested splitting HEOMD would improve management. “The restructuring of NASA’s Human Explorations and Operations Mission Directorate will help us safely and effectively manage this growth in scope,” Melroy said at the town hall meeting. “We have the opportunity to better align our organization structure with increasing activities in LEO and with our developmental exploration architecture, and ensure the workforce has a focused oversight team in place to execute for mission success.”

| “Kathy did such an extraordinary job,” Nelson said of Luders, saying the reorganization was not a reflection of her management of HEOMD. |

Management of HEOMD over its one-decade existence was characterized first by stability and then volatility. When NASA established the directorate in 2011, it picked Bill Gerstenmaier, then the associate administrator for space operations, to lead the combined directorate. He did so for nearly eight years, to almost universal acclaim, until then-administrator Jim Bridenstine reassigned him to a senior advisor role as he sought new leadership to invigorate the Artemis program.

That new leadership came in the form of Doug Loverro, a former Defense Department official, who took over in late 2019. He lasted just six months, though, before resigning in May 2020 after he allegedly provided advice to Boeing’s (ultimately unsuccessful) HLS bid outside of procurement rules. He was replaced weeks later by Kathy Lueders, the longtime manager of NASA’s commercial crew program.

While Lueders was new to many of the exploration programs, she had done by all accounts a good job of running HEOMD for the last 15 months. But many saw NASA’s decision to split HEOMD in two, and place Lueders in charge of the smaller Space Operations directorate, as something of a demotion, perhaps because of how she managed the HLS program and resulting protests by the losing bidders.

Nelson said that was not the case. “Kathy did such an extraordinary job,” he said, again discussing how HEOMD accounted for nearly half of NASA’s budget. “That’s a lot to swallow.” The proposal to split HEOMD into two directorates came from the Biden Administration’s transition team early this year, months before the HLS decision, he said.

“Kathy continually exceeds all expectations,” added Cabana, supporting “extraordinary outcomes.”

Lueders said she looked forward to her new role. “We’re a team,” she said at the town hall meeting. “There will be a transition and sometimes it will be hard.”

Her teammate, the new associate administrator for exploration systems development, is Jim Free. He was a former head of the Glenn Research Center who moved to NASA Headquarters in 2016 to be a deputy associate administrator in HEOMD. He left NASA after about a year at headquarters, though, taking a job in a private sector. Most recently he was a leadership consultant while also chairing the technology committee of the NASA Advisory Council.

“We have in the Exploration Systems Development organization the opportunity to take our approach to development a little bit differently,” he said at the town hall meeting. He didn’t elaborate on those differences but emphasized that the directorate would eventually hand over its systems to Space Operations “and then move on to our next thing, our next development.” (Lueders said that she and Free would later determine when exactly systems developed under his directorate, like SLS and Orion, would move to her directorate.)

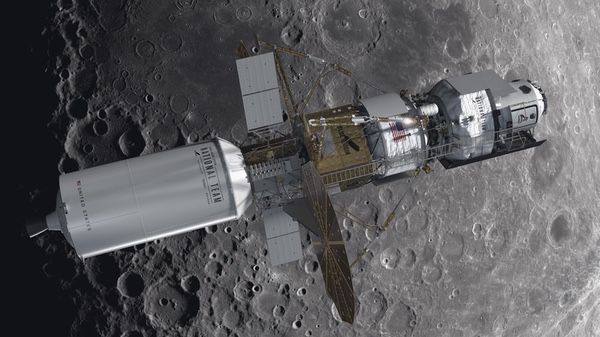

Blue Origin is taking the case over the Human Landing System competition to federal court, saying its concept wasn’t treated the same as SpaceX’s. (credit: Blue Origin) |

The new division of labor also means a division of headaches. Free is now responsible for HLS, including its $2.9 billion award to SpaceX that triggered protests by the two losing bidders, Blue Origin and Dynetics. The Government Accountability Office rejected both protests in late July, appearing to clear the way for NASA to proceed with its work with SpaceX (see “Relaunching a lunar lander program”, The Space Review, August 2, 2021).

However, Blue Origin appealed the protest by filing suit against the government in the Court of Federal Claims, the federal court that adjudicates such protests. That led to an agreement between Blue Origin and the government that requires NASA to again halt work on its award to SpaceX through the end of October on the understanding that the court will rule on the suit by that time.

| “Had Blue Origin known the Agency would waive the FRR requirements and other requirements that greatly impact schedule and risk, Blue Origin would have engineered and proposed an entirely different architecture,” the company claimed in a court filing. |

In a redacted court filing released last week, Blue Origin argues that SpaceX’s proposal was deficient and thus, under the rules of the HLS program, “unawardable” since it did not include flight readiness reviews, or FRRs, before each launch of an element of its Starship lander. In addition to the lander itself, SpaceX proposes as many as 14 launches of “tanker” versions of Starship that will fill the propellant tanks of the lander in Earth orbit before going to the Moon. SpaceX reportedly included an FRR only at the beginning of the series of tanker launches, rather than one for each tanker launch.

The GAO noticed that issue as well but concluded that it didn’t make a difference in the outcome of the competition, finding no evidence other companies “could or would have changed their proposals to substantially increase their likelihood of receiving the award had they known of the waiver of the FRR requirement.”

Blue Origin disagreed. “Had Blue Origin known the Agency would waive the FRR requirements and other requirements that greatly impact schedule and risk, Blue Origin would have engineered and proposed an entirely different architecture with corresponding differences in technical, management, and price ratings,” it claims, but did not elaborate on that that architecture would have been.

Even if the suit is resolved in NASA’s favor, the months of delays would seem to put any chance of an Artemis 3 human lunar landing in 2024 in jeopardy. ““If you have a coin, you can flip it as to what’s going to happen in the legal wrangling that’s going on right now,” he said in the call with reporters last week when asked about the feasibility of a 2024 landing. “What is the federal judge going to decide? When is he going to decide? What are the further legal possibilities about that?”

Nelson has been lobbying for additional funding, on the order of $5 billion, to allow NASA to select a second company for an HLS award, regardless of the outcome of the Blue Origin case. However, the House version of a fiscal year 2022 spending bill provided only a small increase for HLS funding and the House version of a $3.5 trillion “budget reconciliation” spending package offered nothing for HLS. The Senate has yet to take up its version of those bills.

Companies like Nanoracks proposing private space stations fear a “space station gap” if the ISS is retired before commercial successors are ready. (credit: Nanoracks) |

Lueders, as head of Space Operations, must deal with the long-term future of the ISS and plans for commercial successors. There’s widespread support, at least in principle, for extending the ISS until 2030, although a series of incidents on the Russian segment of the station—small but persistent air leaks in one module, and the firing of the Nauka module’s thrusters hours after its docking in July that knocked the station off-kilter—have raised some questions about its long-term viability.

NASA’s focus is on supporting commercial space station developers. Lueders said last week that the agency received more than ten proposals for its Commercial LEO Development program, with NASA expected to pick as many as four for initial studies of commercial stations. The agency’s goal is to have one or more stations in place by the late 2020s, enabling a transition period from the ISS to those commercial successors.

| “I don’t know which one of us is Batman and which one is Robin,” said Lueders. “I have a feeling that every once in a while we’ll be switching back and forth.” |

At a hearing of the House Science Committee’s space subcommittee, taking place at almost the same time as NASA was announcing the split of HEO, industry officials called on Congress to support that program. “There is no room for error lest we cede leadership to other nations,” said Jeffrey Manber, CEO of Nanoracks, warning of a “space station gap” if Congress didn’t act.

That gap, he added, would be filled by China and the space station it is assembling. “I don’t fear cooperation or competition with China,” he said, “but we cannot allow even the perception that we will cede our 20-plus years of humans working in LEO to others.”

Congress has, so far, been reticent to fund commercial LEO development at NASA. In fiscal years 2020 and 2021 NASA asked for $150 million each year, but received only $15 million and $17 million, respectively. In 2022 it asked for $101.1 million, but a House spending bill provides just $45 million.

Funding is likely one of many shared challenges that Free and Lueders will face together as the heads of their mission directorates. “I keep thinking two heads are better than one, and this is going to be a lot of fun,” Lueders said.

“The other day, somebody said, ‘This is going to be so great. You’re the dynamic duo,’” she added. “I don’t know which one of us is Batman and which one is Robin. I have a feeling that every once in a while we’ll be switching back and forth.”

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.