Boozy Chimps in Orbit and intoxicating Saturns: Where space pop meets Tiki cultureby Deana L. Weibel

|

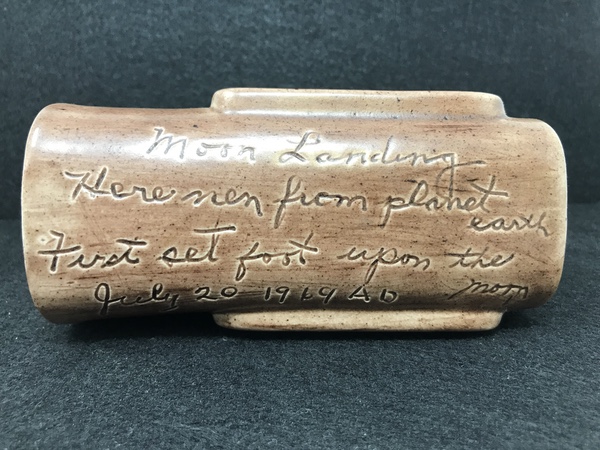

This little Duncan Moai captures the moment when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the Moon. |

The first engraving, written sideways on the back of the Moai’s head in a firm cursive hand, reads:

Moon Landing

Here men from planet earth

First set foot upon the moon

July 20 1969 AD

|

A second engraving marks the bottom of the mug. It is done in a much simpler printed hand and reads:

Men are

on the Moon

at this time

MARTA Z

|

This little Moai mug serves as a sort of a time capsule, an archaeological artifact demonstrating a society’s simultaneous interest in an imagined version of the tropics and enthusiasm about a new territory to explore, the Moon. I purchased the mug right away (I can hear someone faintly crying, “It belongs in a museum!”) and it holds pride of place in my collection.

| If the Tiki culture of the “golden era” could incorporate Samoa and Rio and Barbados and Shanghai, it wasn’t a stretch to include the palms of Cocoa Beach… and from there the Moon? |

While it might seem strange to mark a Tiki mug with memories of the Moon landing, the connection is stronger than it may initially seem. The origins of Tiki are in what Tiki restaurateurs and scholars Martin and Rebecca Cate have called the “Polynesian fad” (2016, 49) that influenced American bars and nightclubs in the 1920s and 1930s. The Cates explain that these Polynesian-inspired watering holes were well-established and remained popular when World War II veterans began to grow nostalgic about the islands, people, and weather they had come to know in the South Pacific (49). Increased traffic to these establishments helped set up the “Golden Era” of Tiki, a period in the 1950s and 1960s marked by dreamy images of grass-skirted island women, surfable waves, Chinese and Japanese cuisine, Caribbean rum, and Brazilian music genres like Bossa Nova. Although the Polynesian foundation of the 1920s and 30s remained in place, by the 1950s restaurateurs and bar owners had added anything and everything Americans considered “exotic.” East and South Asia, the islands of the South Seas, the Caribbean, South America, and sometimes even Africa and the Arabian Peninsula were thrown into a sort of pop culture blender. The cocktail that resulted was one where artifacts, images, and flavors of foreign and unfamiliar places (particularly warm foreign and unfamiliar places) often ended up portrayed together as “Tiki.”

When Disneyland opened in 1955, one of the attractions already in place was Adventureland’s “Jungle Cruise.” Although not a truly “Tiki” attraction itself (although there is an overlap with Tiki themes), the blended exoticism of the foreign and different is very apparent—for instance, the cruise takes guests along “the Mekong River, African Congo, the Nile River and the Amazon” (Jungle Cruise, 2021), a single journey covering Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, and South America. As an interest in Tiki grew, Disneyland became more intentional about its connection to Tiki, bringing “The Enchanted Tiki Room” to Adventureland in 1963, not long after the Polynesian island of Hawaii became the 50th US state (Walt Disney’s Enchanted Tiki Room, 2021).

If Disneyland demonstrates the popularity of the “exotic” in the 1950s and 60s, it also shows how popular America’s nascent space industry was becoming. Guests on opening day in 1955 could ride not only the Jungle Cruise, but also the “Rocket to the Moon” and “Space Station X-1,” attractions that offered the adventure of space travel (Newell, 2013). America had entered a postwar period marked by dreams of distant places (whether Maui or Mars) and where advanced technology and so-called “primitive” places seemed to converge.

If the Tiki culture of the “golden era” could incorporate Samoa and Rio and Barbados and Shanghai, it wasn’t a stretch to include the palms of Cocoa Beach… and from there the Moon? If most Earth people couldn’t join the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo astronauts as they drifted in microgravity, at least they could feel themselves float a bit after a Chimp in Orbit (which Tiki expert Jeff “Beachbum” Berry dates to 1961 (2017, 147)), or a Saturn (1967, according to Berry (2013, 87)).

By the late 1970s, Tiki style had largely been rejected by mainstream American culture as hopelessly uncool and tone-deaf. Sven Kirsten credits its revival, in part, to “ex-adherents of punk and new wave music, always fond of the different and obscure, (who) began to appreciate the then-unfashionable lounge and exotica tunes of the cocktail generation,” (2014, 367) a claim that feels both unfairly personal and absolutely accurate to this author. Kirsten argues that these youthful explorers went from music to mugs to drinks and art, bringing Tiki back as a phenomenon, although not as ubiquitous as it had been in previous decades. Martin and Rebecca Cate note that the Tiki Revival, as it came to be known, hit different people in different ways, explaining, “Decoding the secret formulas behind the exotic cocktails became the passion of some, while others studied the art, architecture and aesthetic” (2016, 75).

Many in the new generation of Tiki lovers were interested in Tiki somewhat ironically, at least at first, appreciating the tang of camp or kitsch it offered (for more on the kitsch of Tiki, see Carroll and Wheaton, 2018). They began to associate Tiki with the pop culture context of the 1950s and 1960s, which included not just monster movies and surf rock, but also space capsules, astronauts, and satellites. A 2020s Tiki spot could conceivably feature music by Dick Dale, drinks named for characters on Gilligan’s Island, the Creature from the Black Lagoon emerging from the straw thatch above guests’ heads, mugs shaped like astronauts, and art based on Disneyland attractions like the aforementioned Jungle Cruise. Even 1980s pop culture that references the ’50s and ’60s (like Pee-Wee Herman and Elvira, Mistress of the Dark) is fair game in some Tiki establishments.

| Although there don’t seem to have been a lot of explicitly space-themed Tiki designs produced during the space race, the juxtaposition of “primitive” islands and the amazing technological leaps from the period seem to have resonated with the American public. |

There’s a lot of culture in Tiki culture. What I plan to consider in this paper, however, are aspects of Tiki culture where depictions of and ideas about space exploration started and remain strong: Tiki mugs, Tiki drinks, and Tiki art. Why is there a significant overlap between space pop and Tiki culture and what does this reveal about the relationship between imagined island paradises and the incredible feats of technology that allow humans to live in the dangerous non-paradise of space? I want to clarify that the “space Tiki” I’ll be examining is not primarily what can be called science fiction Tiki. Quite a bit of the monster movie genre involved aliens and UFOs and there is a large amount of Tiki style reflecting those tropes, as well as lots of new Tiki merchandise connected to more recent science fiction, like Star Wars, Star Trek, the Avengers, etc. Instead, I’m primarily looking at Tiki paraphernalia, images, and ideas specifically associated with Sputnik, the space race, the moonshot, and other endeavors undertaken by real-life Earthlings, an area that may reflect nostalgia more than contemporary fandom.

Although there don’t seem to have been a lot of explicitly space-themed Tiki designs produced during the space race, the juxtaposition of “primitive” islands and the amazing technological leaps from the period seem to have resonated with the American public. The “exotic” locales of the South Seas and other romanticized island-dotted areas were connected to rockets, astronauts, and Moon voyages via space-race adjacent phenomena like the A-bomb tests performed on the Bikini Atoll (see Weisgall, 1994) and because of post-space mission splashdowns taking place in or near the Caribbean and the South Pacific.

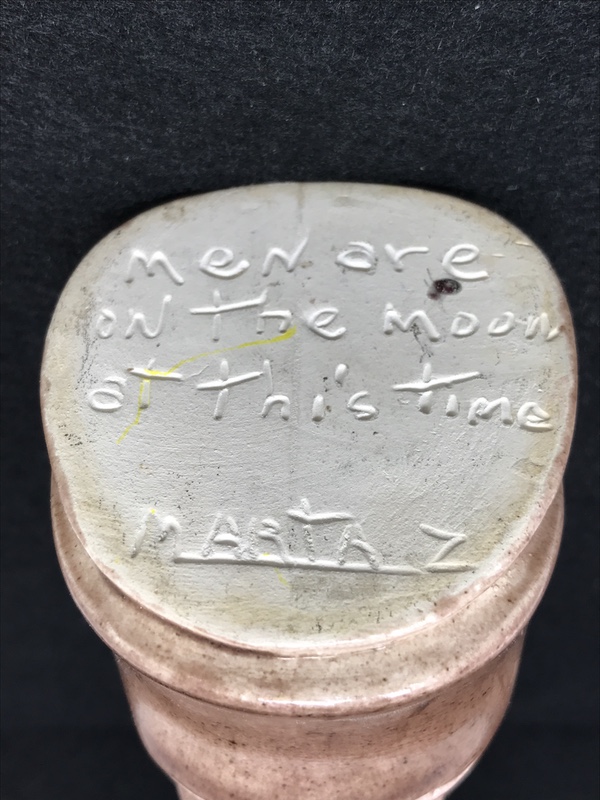

A photo from the Philadelphia Inquirer, April 19, 1970. |

The crew of Apollo 13, for instance, after surviving a harrowing ordeal that nearly killed them all, splashed down successfully in the Pacific and were welcomed as heroes in American Samoa before traveling to Hawaii. Newspaper and magazine photos depicted the ultramodern heroes bedecked with leis and honored by local peoples performing a “ritual dance.”

A clipping from the Philadelphia Inquirer, April 19, 1970. |

In one fascinating occurrence, an article from the Fort Worth Star Telegram on March 16, 1966, had the headline “New Zealand Presents Tikis to 2 Astronauts.” The uncredited report from the Associated Press reads:

When astronaut Walter M. Schirra Jr. makes his next space flight he may be wearing a greenstone tiki, a maori [sic] charm around his neck.

Schirra and astronaut Frank Borman received tikis on silver chains at a reception in the Town Hall today from Mayor Roy McElroy.

Schirra had difficulty getting the chain over his head. When McElroy said he hoped the astronauts would wear the tikis on their next flight, Schirra answered: “I suspect I shall. I don’t think I’ll be able to get it off.”

A clipping from the Fort Worth Star-Telegram from March 16, 1966. |

Apollo crews were also often sent to the Big Island of Hawaii for geological training (CBS News, 2019). It seems astronauts during this period were always visiting “exotic” islands for one reason or another, and that many NASA personnel were just plain attracted to Tiki design and drinks. A terrific thread on Tiki Central called “Tiki connections to Space Age pioneers” (thanks to “The Professor” for the tip) covers such topics as Wernher von Braun’s visits to Trader Vic’s, a Tiki bar-themed rocket designed by a group of space engineers, and Apollo astronaut Al Worden’s adventures at the “Tahitian Village” in Downey, California.

A fictional example of this type of convergence occurred during season three of the popular romantic-comedy-fantasy television series, I Dream of Jeannie, when multiple episodes in the 1967–1968 season were set in Oahu. In the series, the beautiful, naïve blonde Jeannie is a literal genie, a term derived from the Arabic word jinn. In Islam, jinns are invisible beings made by God from smokeless fire (unlike humans, who were made from dry clay), who may sometimes be brought under human control (see Taneja 2020). Although Jeannie’s name and magic connect her with the story of Aladdin and other Arabian tales of genies, in the series introduction her “master,” astronaut Tony Nelson, finds her bottle on a deserted island (presumably in the South Pacific) after splashing down in his Mercury-type spacecraft. He opens the bottle, releasing her and gaining access to her power to grant wishes.

In season three, one of their adventures in Hawaii involves Tony and fellow astronaut Roger Healy using their NASA affiliations to meet girls on Waikiki beach then enjoying Tiki cocktails and the musical stylings of singer Don Ho at the Canoe House in the Ilikai Hotel (Guzmán, 1967). In another, Jeannie brings 19th century Hawaiian monarch King Kamehameha forward in time to contemporary Oahu, where Tony attempts to convince the appalled and disoriented ruler of the benefits of technological progress in his paved-over paradise. As Tony explains to Jeannie and Roger, Kamehameha must “be made to understand what civilization has done for the country… He’s…just not used to all this. He just doesn’t know, you know, how to cope yet… He’s got to be made to see what civilization has helped, and the progress that’s been made here” (Cooper, 1968). In this episode the technological modern confronts the “uncivilized” past head-on, demanding its superiority be recognized.

Providing something of an expansion of the viewpoint taken by the fictional Tony Nelson is scholar Andrew Pilsch, whose work generally considers the impact of digital culture on humanity. Pilsch explored Tiki and technology in his 2020 article, “Polynesian Paralysis: Tiki Culture and the Aesthetics of the American Empire.” He describes Tiki as “a primitive-futurism, blending militarism and rapid technological change with rhetorics of slowness and primitivism into the same complex brew” and notes that creating the correct “Tiki” atmosphere of escape from modernity and technology actually requires technology—the use of blenders to make specific Tiki drinks, for example (229). Post-war Americans’ sudden ability to conveniently reach the tropical paradise of Hawaii in just a few hours was itself predicated on the use of 707s that were “based on airframes capable of obliterating all life on Earth” (234). World War II technology, as bloody as it was, opened the gates of paradise.

| Space imagery in a Tiki bar, then, probably started as a mostly unconscious but deeply powerful alignment of the “primitive” and progress (particularly technological progress) writ small. |

The approach to Tiki culture taken after the war was, among other things, an effort by a new superpower to convince itself of its role in the much older European colonial enterprise. As Pilsch explains, “Tiki culture…produced a postmodern aesthetic to explain Jet Age America’s global reach and to produce an impression of a longer, aesthetic imperial past” (226). In this view, one of the reasons Tiki bars and drinks were so popular during the space age was because the South Seas and other tropical destinations had been “won” through American military might, giving the US a right to the colonial trappings more associated with the British Empire. Tiki is simple and Edenic on the surface, but deeply connected to World War II, nuclear testing, and astronaut splashdowns.

Space imagery in a Tiki bar, then, probably started as a mostly unconscious but deeply powerful alignment of the “primitive” and progress (particularly technological progress) writ small. It continued to appear throughout Tiki culture, particularly in the contemporary “Third Wave” of Tiki (Food Republic, 2015) from whose long-range perspective the connections between tropical islands and the space race are more obvious. Turning to some concrete examples of the manifestation of Pilsch’s “primitive-futurism,” I’ll start with art you can sip from: the Tiki mug.

According to Tiki expert Sven Kirsten, Trader Vic was “the pioneer of the South Seas-themed cocktail container” (2014, 201). Vic began using a skull-shaped mug as early as 1944 (for serving drinks like Hot Buttered Rum and the Goddess of Love) but he also used other containers, like his Kava Bowl, based on “original Polynesian bowls and containers” (2014, 200–201). Polynesian and nautical-themed spots at the time also frequently served drinks in hollowed-out coconuts and pineapples (204). Eventually the creation of mugs became more intentional. Kirsten writes that sacred Hawaiian ritual vessels “prompted Trader Vic in the early 1950s to commission California artist Dickman Walker to create a Tiki bowl for his bar menu,” a piece Kirsten identifies as “the first Tiki cocktail container” (202, see also an image of the bowl).

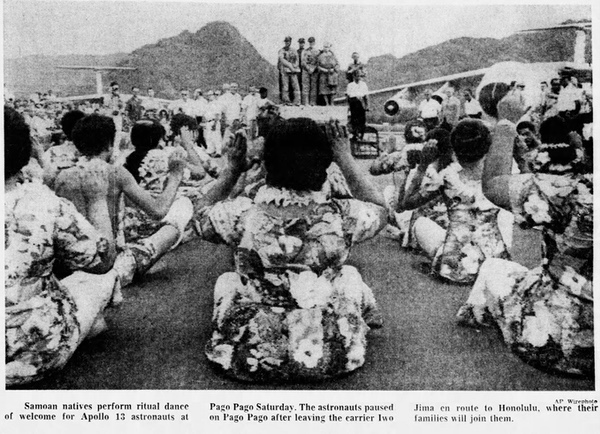

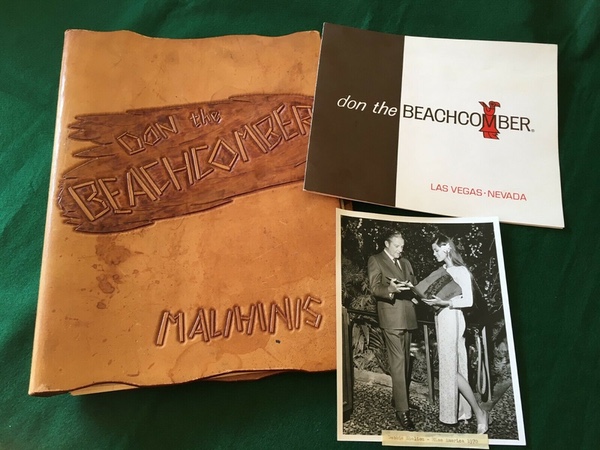

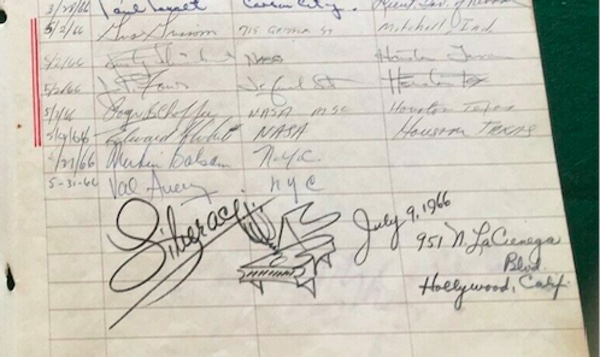

The origins of the Tiki mug (as opposed to the Tiki bowl) are more mysterious. It is possible, per Kirsten, that the first Tiki mug was either a Tiki Bob (a classic mug depicting a smiling face carved into a palm tree (“Tiki Bob,” 2021) or an Islander mug (which depicts a Western image of a fierce-faced “headhunter,” complete with a bone in his nose (“Islander Headhunter Mug – Tiki Mug,” 2020)) (203), but what is clear is that mugs made popular souvenirs from Tiki bars. They began to proliferate, becoming ubiquitous in the late 1950s and early 1960s, just as the space race pitting the USA against the USSR was intensifying. Although we know there were occasional astronauts in Tiki bars—a recently auctioned guestbook from Don the Beachcomber in Las Vegas featured several astronaut signatures, including those of Gus Grissom, Ed White, Roger Chaffee, and Rusty Schweickart, who visited on May 2, 1966 (thanks to Emily Carney for the tip!)—space-themed Tiki mugs from the era were either rare enough to have completely disappeared or never existed at all.

Astronaut autographs from a 1966 visit in a Don the Beachcomber guest book. Photo, author's collection. |

During the Tiki resurgence that began in the 1990s and continues today, however, astronauts and other space-age themes have become common in Tiki mug design. Aliens and UFOs have shown up frequently in present-day Tiki mugs, both “classic” spacemen from popular 1950s and 1960s movies like The Day the Earth Stood Still, and products designed for more contemporary fandom, like the Geeki Tiki company, which produces Tiki versions of protagonists and alien villains from popular franchises like Star Trek (James T. Kirk, Jean-Luc Picard, the Borg) and Star Wars (Leia Organa, Grogu, Jabba the Hutt). In a similar vein, the classic UFO shape can be found in more recently-produced mugs, like Thor & Gecko’z UFO Tiki Mug and Moai Spaceship, by John Mulder.

Robots, specifically space robots, are another contemporary sub-genre. Tron the Beachcomber and Radar Vic (named for famed Tiki empresarios Don the Beachcomber and Trader Vic, and designed by Scott Scheidley) look something like Tikis wearing spacesuits.

The Radar Vic. Photo by author. |

Another example is based on an image from the science fiction retelling of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, a movie called Forbidden Planet. In one scene Robbie the Robot carries an unconscious Altaira Morbius (as played by Anne Francis), and the Taboo Planet mug (designed by Patrick Vassar) recreates this scene with a Tikified robot carrying a limp blonde hula dancer.

Tiki mugs based on the actual spacecraft and spacesuits from Tiki’s golden age aren’t difficult to find. One of the more recognizable is Thor’s Sloshed in Space mug, featuring a spacewalking astronaut floating outside his capsule with a Tiki Bob mug in his gloved hand.

“Sloshed in Space” by Thor (Tom Thordarson). Photo used with permission of artist. |

Space historian Glen E. Swanson (my husband) assures me that while the tapa-patterned capsule looks like it’s from the Mercury program the spacesuit is clearly from the Gemini program. Despite this historical mashup, both elements of the mug are easily recognizable and clearly inspired by actual space-race tech.

Another such quasi-realistic Tiki mug is the Astronaut Tiki Mug from the Saturn Room. According to mytiki.life author “Trader Tom,” the mug features a Tiki resembling the iconic and rather rare Frankoma Pottery’s “Tiki God” wearing a spacesuit, although Swanson was less-than-impressed with its technological accuracy, calling the suit “fanciful” and saying the spacesuit’s gloves look “like oven mitts” (Swanson, 2022).

“The Astronaut Mug” from the Saturn Room. Photo by author. |

Finally a third astronaut-themed mug, presumably still in the works, is Millie’s Light Year Lounge, a mug announced by website The Search for Tiki in July 2020. According to Gabriel Bascom, “The Millie’s Light Year Lounge mug depicts a female astronaut floating outside a rocket ship. Moons and a planet also decorate the ship, along with the written text, “Light-Year Lounge” (Bascom, 2020). As of this writing, it’s not clear when (and even whether) the mug is still being planned for release.

Another Tiki area where realism plays something of a role is in mugs that resemble actual spacecraft and satellites. A “Tiki Weekender” event held near Cape Canaveral in Florida inspired a “Space Coast” Tiki mug featuring a Tiki holding a rocket (“Captain Dock,” 2020). More fantastic rockets can be found as well. Eric October’s “Tiki Bob to the Moon” is a two-piece set featuring a moon-shaped bowl and a Tiki Bob “rocket,” recreating the Moon landing from George Méliès’ 1902 silent movie Le Voyage dans la Lune. Meanwhile, the Intergalactic Island Hopper (also designed by Scott Scheidley), although featuring an alien, is another example of a whimsical rocket. This version of the Hopper was painted by Tiki artist Dawn Frasier.

Intergalactic Island Hopper, photo by Dawn Frasier. |

Finally, a forthcoming mug is the Sput-tiki, designed by Ken Holewczynski to resemble Sputnik, the tiny Soviet satellite whose orbit terrified Americans and started the space race in 1957. Holewczynski intended to release the mug in the spring of 2022 but held back following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The Sput-Tiki, photo by Ken Holewczynski. |

Like traditional Tiki mugs, which feature mermaids, coconuts, nautical imagery or, well, Tikis, space Tiki mugs impart something exotic to their contents. Space-themed Tiki art, used to decorate both professional and home-based Tiki bars, also creates a particular mood.

One of the most common places for the intersection for space pop and Tiki pop is in the area of décor, particularly paintings and other works of two-dimensional art. These visual displays follow some of the themes of Tiki mugs but aren’t limited to what can be expressed in ceramics of a certain size. Many artists whose work encompasses a large range of Tiki themes have particular pieces with a space-age flavor that express a specific mood or even zeitgeist.

An artist particularly known for his space-themed art is Josh Agle, more commonly referred to as Shag. Sven Kirsten has described Shag’s style as “interstellar Tiki” (2014, 368) and many of his works tie space and Tiki themes together. Some of his art has a science fiction focus, like his Planet of the Apes series (based on the original 1968 movie) and the Star Wars prints and products he has created for Disney.

| The combination of sleek MCM architecture and styling with the rockets and Moai invoke instead a sort of Camelot-era utopia. |

Other items reflect a particular intersection of Tiki and space that recalls the ancient astronaut or ancient alien hypothesis, a popular contemporary myth that credits prehistoric feats of human engineering like the Mayan pyramids and the Moai on Rapa Nui to extraterrestrial technology (see Hammer and Swartz, 2021), such as “Forbidden Planet.” In Shag’s Forbidden Planet picture, space-suited astronauts with Moai heads encased in bubble helmets shoot lasers while floating near speeding rockets, in apparent orbit around a heavily cratered greenish-yellow planet. One interpretation of this fanciful image may be that the statues on Rapa Nui themselves (often used as a sort of Tiki exemplar in Tiki art) may have been an accurate representation of the aliens who erected them. I suspect that the artwork is playfully referencing the ancient astronaut theory rather than espousing it.

Some of Shag’s art portrays space exploration in a more historically accurate way, although questions of authenticity may still be raised. “Space Widows,” for instance, depicts Americans in a cityscape viewing the July 20, 1969 NASA Moon landing on TV in their apartments (some depicting Tiki design elements) and through the window of a street-level TV shop. This was a moment in history when, according to Shag himself, “Many women lost their husbands to the Television that evening!” Despite the artist’s assumption that women were somehow less interested in the Moon landing than men, articles about the powerful draw of the first crewed Moon landing note that it was, at the time, the most watched televised event ever (until the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana in 1981.) Nothing I could find indicated a distinction between male and female viewership (Hsu, 2019) and even in Shag’s painting, most of the women depicted appear to be watching the event themselves.

In contrast to the idea of “Space Widows,” art by Linda Tillman features women very prominently, albeit as sort of glamorous pin-up girls or beach bunnies. Their settings are a very third-wave Tiki combination of space rockets and Tiki figures, similar in feel to Shag’s aforementioned “Forbidden Planet.” “Tiki Beach Girl” reclines in a chartreuse yellow hammock held up by the teeth of two enormous Tiki figures. The “girl” smiles in sunglasses and a green bikini as a rocket lifts off from a volcano in the scene directly behind her (variations of the original painting feature different girls with different hammocks or hats, but all with the volcano rocket).

Tillman’s “Retro Future” is more complicated, with a Jackie Kennedyesque woman in a red dress leaning over the balcony of a Mid-Century Modern (MCM) building. The balcony overlooks a swimming pool and a group of four dogs who all appear to be watching the flight of twin rockets. A collection of more than a dozen Moai sits beside the pool and in the distance, across an expanse of water, is a city skyline with a monument resembling the Space Needle and a third rocket that appears to be lifting from a distant launch pad. Two additional rockets stand at rest near the dogs.

Most of Tillman’s paintings, unlike Shag’s “Forbidden Planet” don’t evoke an Ancient Alien feel. The combination of sleek MCM architecture and styling with the rockets and Moai invoke instead a sort of Camelot-era utopia. Aliens don’t seem to play a role and there is nothing unsettling. Instead, Tillman’s tropical and high-tech elements work together to create a sense of glamour and luxury and give the impression that the best of the old is in careful balance with the best of the new. Pilsch’s primitive-futurism is again on display.

Another Tiki artist whose work veers into more (and sometimes less) realistic depictions of 1950s and 1960s space pop is Doug Horne. Like Linda Tillman, Doug Horne brings the pin-up girl into his space Tiki imagery sometimes, such as in his work “Space Betty Page.” This painting, a fever dream of Tiki pop, 50s sex appeal, monster movies and NASA adventure, features a green-skinned Bettie Page (who is also a giantess and has sprouted a pair of antennae) lounging in a leopard bikini on a crater-filled moonscape. Strange plants seem to grow around her and a planet resembling Jupiter (featuring two moons) rises from the horizon behind her. Between her left index finger and thumb, she suspends a writhing astronaut in full spacesuit and holds him up for a better look, a mischievous (malevolent?) grin on her face.

| While it is unlikely that a typical imbiber would believe drinking a Space Pilot would turn someone into an astronaut, the sensation of floating or flying produced by a strong enough drink combined with the power of suggestion probably helped make the drink particularly popular. |

Still fantastical but somewhat more grounded, is Horne’s “NASA Monkey Takes a Break.” I confess to owning a print of this painting and it’s one of my favorite works of the genre. An exhausted looking chimpanzee (perhaps Ham or Enos—see Reynolds et al, 1969, and Burgess and Dubbs, 2007, for more on NASA’s use of chimpanzees in space) sits at the bamboo bar in a Tiki joint, the cigar in his mouth creating a cloud of smoke overhead. The spacesuit-wearing chimpanzee’s left arm rests on his space helmet while his right hand clasps a Tiki mug, complete with pink umbrella. The tired primate stares wearily at some traditional objects of Tiki décor (a green glass fishing float and a turquoise puffer fish lamp) while a large Tiki sits expressionless behind him. The subject of this painting is clearly a hardworking astrochimp, deserving a moment of rest in a Tiki bar. If human astronauts Grissom, White, Chaffee and Schweickart got to go to Don the Beachcomber in 1966, it would clearly be unfair to deny this NASA “monkey” a similar refreshment. Coincidentally enough, drinks are our next topic.

While space-themed phenomena aren’t common among the art and mugs of Tiki’s golden age and seem to be much more at home in the Tiki revival’s tendency to nostalgically incorporate diverse elements of 1950s and 1960s popular culture, space-themed Tiki cocktails did exist during Tiki’s earlier incarnations.

It isn’t surprising, given Tiki bars’ large customer base of veterans who had spent time in the Pacific theater during World War II, that quite a few early Tiki drinks had a military bent. Even before the War, in 1937, Don the Beachcomber served a drink known as the Q.B. Cooler, a nod to the aviation fraternity known as the Quiet Birdmen. Berry notes (2017) that the group was a “drinking fraternity” that was created by a small group of World War I pilots in 1921 (162). Given the number of Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo astronauts who got their start as Air Force or Navy pilots, it makes sense that many of them joined the Quiet Birdmen. This allows the Q.B. Cooler (which is rumored to have inspired the Mai Tai) to serve as a very early example of a space-related Tiki drink.

More obvious is a mercurial drink (no pun intended) that has changed names and ingredients over the decades, transforming from the Test Pilot in 1941 to the Jet Pilot in 1958 and the Space Pilot in 1961 (Berry 2010; Hurricane Hayward 2022). Aviation-themed drinks recalled the glory days of flyboys in the South Seas, but also allowed the drinker to participate in a bit of vicarious derring-do, similar to what anthropologists refer to as “sympathetic magic” (Frazer 2020, originally 1889). As Frazer explains, following the magical principle of “similarity,” “the magician infers that he can produce any effect he desires merely by imitating it.” While it is unlikely that a typical imbiber would believe drinking a Space Pilot would turn someone into an astronaut, the sensation of floating or flying produced by a strong enough drink combined with the power of suggestion probably helped make the drink particularly popular.

“Pilot” drinks have also been an important part of the Tiki revival. Beachbum developed a recipe for the cosmonaut-inspired Coconaut (and its variant the Coconaut Re-Entry) in 1994 (Berry and Kaye 1998). Berry also cites the Voyager (credited to Robert Hess), as having been at least partly inspired by Hess’s enthusiasm for the various Star Trek series (2010, p 216).

Before test-pilots-turned-astronauts went into space, however, the necessary procedures were tested by chimpanzees, namely Ham and Enos, who inspired their own cocktails. The drink “Chimp in Orbit,” a 1961 concoction apparently inspired by Ham and credited to Harry Yee of the Hilton Hawaiian Village (Berry 2017, 147) is one such example, as is the much more banana-forward (and more recent) Astrochimp, served at my local Tiki palace, Max’s South Seas Hideaway.

An “Astrochimp” from Max’s South Seas Hideaway in Grand Rapids, Michigan. |

The dual association of chimpanzees (and monkeys) with the tropics (although orangutans would be far more accurately “South Seas” than chimpanzees) and with the American space program (the Soviets tested spacecraft with dogs and turtles, not chimpanzees) means that the chimpanzee is an important crossover in terms of iconography, linking Tiki and space. The space-chimpanzee connection provides an excellent contrast between “primitive” and “advanced,” since chimpanzees and monkeys are often associated with evolution and pre-human ancestors. The image of a chimp in a spacesuit, then, serves as a great example (once again) of Pilsch’s “primitive futurism.”

A similar juxtaposition of “primitive” apes and “advanced” technology is made in the original 1968 film Planet of the Apes, which sees a trio of American astronauts landing on an unfamiliar world populated by “civilized” chimpanzees, orangutans, and gorillas. Jeff “Beachbum” Berry created his own Planet of the Apes cocktail in 1995 and artist Shag has a series of paintings depicting the characters from the movie in Tiki settings.

Additional space-themed cocktails are named for planets and other places in space. The gin-based Saturn, created in 1967 by “Popo” Galsini (Berry 2013) is one example, with its cherry-ringed-by-a-lemon-peel garnish (although it was actually inspired by the extremely powerful Saturn V rocket developed during the Apollo program), as is the rum and raspberry-flavored Center of the Galaxy concocted by Martin Cate in 2009 (Cate and Cate, 2016). Other drinks have space-themed names that appear to combine space terminology with South Seas place names or legends (like Berry’s Astro Aku Aku and Aurora Bora Borealis, 2010, 30).

A Saturn cocktail, made and photographed by the author at home. |

Of course, the space-themed cocktail is not always Tiki. There are drinks based on the purported-but-unproven astronaut “favorite” Tang, like the Buzzed Aldrin and the Astronaut Sunrise (a variation of the Tequila Sunrise), and a wide variety of drinks with space names like the Jupiter, the Sputnik, and the Skyrocket Cocktail. One fascinating drink that isn’t Tiki but whose authenticity deserves mention is the Moonwalk.

| It reminds us that now that humans have waded into the great vastness of outer space our inspirations should include the successes of the skilled settlers of Tahiti, Bora Bora, Upolu and Atiu who, centuries ago, voyaged into another open expanse and mapped it carefully, one new mooring at a time. |

According to online magazine Sauveur, “In 1969, Joe Gilmore, head barman at Savoy Hotel’s American Bar in London, invented this citrusy champagne cocktail to commemorate the Apollo 11 moon landing. The Moonwalk—“a lively combination of grapefruit juice, orange liqueur, and a hint of rose water, topped with bubbly—was the first thing astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin sipped upon returning to earth” (Sauveur 2014). An August 1969 AP article explains further that Gilmore sent a bottle of Champagne and a canister containing the “fixins” (the other cocktail ingredients) to Houston for the astronauts to combine together and drink when they got out of quarantine (“Moonwalk Cocktail for Astronauts,” 1969).

Tiki expert Shannon Mustipher writes, “Tiki cocktails, and the experience around them, are intended to be transportive” (2019, 7). As discussed above, there seems to be an element of sympathetic magic in the space-themed cocktail. Names hold power and naming a drink after a space traveler, a planet, or other space phenomena seems to confer “spaciness” on the drinker. Cocktail names in places as atmospheric as Tiki bars enrich the experience. It is certainly more fun to drink a Center of the Galaxy than it would be to drink something called Rum Cocktail 12a (although the actual astronauts I’ve known have seemed to prefer spirits on the rocks, such as Tito’s Vodka or Bombay Sapphire Gin, to fancy cocktails.) A person sipping a powerfully named space-themed drink in the “exotic” atmosphere of a Tiki bar is drinking in a specific vision of the future based on and set in a faraway depiction of the past.

Tiki mugs, art and drinks are only three points of intersection between Tiki fantasies and space-age pop. There are far too many other phenomena that sample from Tiki and the space age to cover here. I do want to draw the reader’s attention, however, to the brilliant Tiki/Space crossover lounge music that was written during the space race, such as Les Baxter’s 1958 album Space Escapade. Italian author Francesco Adinolfi beautifully describes the intended effect of this enchanting collection of songs:

Suddenly, the outer space conjured up by science fiction films made its way into living rooms by way of new stereo systems’ speakers. Listeners could close their eyes and land on the moon or Mars, transported by a floating sound that rapidly panned from right speaker to left speaker and back to the right once more. The domestic easy chair assumed the form of an unusual spaceship from which to reach out and, as on the cover of Space Escapade, grab hold of multicolored cocktails, seemingly alien but truly very close to home and reassuring (2008, 146).

Space Escapade was only one of many albums released during this era that created a similar “vibe” (see, for instance, Walter Schuman’s breathtaking 1955 album, Exploring the Unknown).

Andrew Pilsch’s argument that this mingling of space exploration and South Seas exoticism is a story of the way technical know-how allowed access to forbidden paradises is convincing, but it’s not the whole story. Part of the reason this connection seems so fitting is that the space age has turned our planet from the “entire world” to (to borrow the name of the classic film) This Island Earth and Earthlings into “primitives” when compared with what the Drake equation (developed by astronomer Dr. Frank Drake as a means of estimating the number of intelligent extraterrestrial civilizations in our galaxy) assures us are countless civilizations in other solar systems.

Like the Polynesian sailors who used the stars for navigation, American astronauts since the 1960s have struck out from the one inhabited place we’re sure of into an endless sea of stars (astronaut means “star sailor” while cosmonaut means “universe sailor”) with the possibility of shipwreck on another lonely island. The 1964 movie Robinson Crusoe on Mars makes this comparison very clearly, retelling the story of shipwrecked Robinson Crusoe in the space age and even supplying him with an escaped slave (in this case an alien) and a space agency-issued monkey as companions.

The idea that Earth is a distant and desolate outpost is also reflected to some idea in the “ancient aliens” tales and their counterparts in Tiki design. In these contemporary legends, primitive looking figures serve to obscure the incomprehensible technology of a far-advanced society (and the Moai of Rapa Nui are reimagined as symbols from a science we can’t understand). There is an appeal to these stories, and at least one of the astronauts I’ve interviewed believed that the human species was created by an alien race mistaken for gods whose details are hidden in ancient mythology (see Weibel, 2020).

When the Russian and American space programs first sent humans into space, the balance between what had been successfully explored and what was left to explore shifted. The superpowers were reasonably sure, after decades of colonialism and multinational wars, that there weren’t a lot of lost continents or hidden civilizations left to uncover on our home planet. Sending humans into space and returning them safely home, however, meant that “terra incognita” had expanded exponentially. If we could walk on the Moon, then surely we could walk on Mars, fly through the clouds of Venus, establish colonies on all of Jupiter’s moons (except, of course, Europa.) Exploration was no longer confined to the territories of Earth – very suddenly exploration became unbounded. As another one of the astronauts I interviewed put it, if you take the whole universe into account, the Moon landing wasn’t a big deal, just “...three guys that didn’t go anywhere and didn’t spend any time doing it.”

If Tiki culture is a technologically dependent celebration of the “exotic,” an attraction to distant places that can nevertheless be reached by air in hours and seen in exquisite detail from the satellites that fly over every day, then the inclusion of space pop in Tiki culture is significant. It serves as an admission that what we know beyond our colonized and decolonizing world is limited. It reminds us that now that humans have waded into the great vastness of outer space our inspirations should include the successes of the skilled settlers of Tahiti, Bora Bora, Upolu and Atiu who, centuries ago, voyaged into another open expanse and mapped it carefully, one new mooring at a time.

Adinolfi, Francesco. Mondo Exotica: Sounds, Visions, Obsessions of the Cocktail Generation. Duke University Press, 2008.

Bascom, Gabriel. “Taboo Relics Announces a Space-Themed Mug.” The Search For Tiki, 31 July 2020.

Baxter, Les. “Space Escapade.” Capitol Records, Capitol Records, 1958.

Berry, Jeff, and Annene Kaye. Beach Bum Berry's Grog Log. SLG Publishing, 1998.

Berry, Jeff. Beachbum Berry Remixed: A Gallery of Tiki Drinks. Club Tiki Press, 2010.

Berry, Jeff. Beachbum Berry's Sippin' Safari: In Search of the Great "Lost" Tropical Drink Recipes … and the People behind Them. Cocktail Kingdom, 2017.

Berry, Jeff. Beachbum Berry's Taboo Table: Tiki Cuisine from Polynesian Restaurants of Yore. Club Tiki Press/SLG Publishing, 2013.

Burgess, Colin, and Chris Dubbs. Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle. Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

"Captain Dock". “2018 Tiki Weekender Mug #79 - Tiki Mug - Captain Dock.” Mytiki.life, 30 May 2020.

Carroll, Glenn R., and Dennis Ray Wheaton. “Donn, Vic and Tiki Bar Authenticity.” Consumption Markets & Culture, vol. 22, no. 2, 2018, pp. 157–182.

Cate, Martin, and Rebecca Cate. Smuggler's Cove: Exotic Cocktails, Rum and the Cult of Tiki. Ten Speed Press, 2016.

Cooper, Hal, director. I Dream of Jeannie: The Battle of Waikiki. Sidney Sheldon Productions/Screen Gems, 1968.

Food Republic. “6 Bars Ushering in Tiki's Exciting 3rd Wave.” Food Republic, 6 Jan. 2015.

Frazer, James George. The Golden Bough. Duke Classics, 2020.

Guzmán, Claudio, director. I Dream of Jeannie: Jeannie Goes to Honolulu. Sidney Sheldon Productions/Screen Gems, 1967.

Hammer, Olav, and Karen Swartz. “‘Ancient Aliens.’” Handbook of UFO Religions, edited by Benjamin E. Zeller, Brill, Leiden, 2021, pp. 151–177.

Haskin, Byron, director. Robinson Crusoe on Mars. Paramount Pictures, 1964.

Holewczynski, Ken. “Personal Communication.” 18 May 2022.

Hsu, Tiffany. “The Apollo 11 Mission Was Also a Global Media Sensation.” The New York Times, 15 July 2019.

Hurricane Hayward. “Mai-Kai Cocktail Review: Jet Pilot Soars over Its Ancestors with Flying Colors.” The Atomic Grog, 17 Jan. 2022.

“Islander Headhunter Mug - Tiki Mug.” Mytiki.life, 23 Apr. 2020.

Kahn, Miriam. “Tahiti Intertwined: Ancestral Land, Tourist Postcard, and Nuclear Test Site.” American Anthropologist, vol. 102, no. 1, 2000, pp. 7–26.

Kirsten, Sven A. Tiki Pop: America Imagines Its Own Polynesian Paradise = Tiki Pop: L'Amérique rêve Son Paradis Polynésien. Taschen, 2014.

“Moonwalk Cocktail for Astronauts.” San Antonio Express, 7 Aug. 1969, p. 7.

“Moonwalk.” Saveur, 17 Oct. 2014.

Mustipher, Shannon. Tiki: Modern Tropical Cocktails. Rizzoli, 2019.

Newman, Joseph M. and Jack Arnold, directors. This Island Earth. Universal-International, 1955.

Pilsch, Andrew. “Polynesian Paralysis: Tiki Culture and the Aesthetics of the American Empire.” The Shaken and the Stirred: The Year's Work in Cocktail Culture, edited by Stephen Schneider and Craig N. Owens, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, 2020.

“Rare NASA Photos of Apollo Astronauts Training in Hawaii.” CBS News, CBS Interactive, 11 July 2019.

Reynolds, H. H., et al. “Discussion Paper: Demonstration of Experimental Techniques Using Nonhuman Primates.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 162, no. 1 Experimental, 1969, pp. 381–386.

Schumann, Walter. “Exploring the Unknown.” RCA Victor, RCA Victor, 1955.

“Splashdown.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 11 Feb. 2022.

Swanson, Glen E. “Personal Communication.” 20 May 2022.

Taneja, Anand Vivek. “Jinnealogy: Archival Amnesia and Islamic Theology in Post-Partition Delhi.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, vol. 3, no. 3, 2020, pp. 139–165.

“Tiki Bob.” The Search For Tiki, 3 Feb. 2021.

"Trader Tom". “Astronaut Tiki Mug - First Edition - Blue - for the Saturn Room -...” Mytiki.life, 17 Apr. 2021.

"Trader Tom". “Tiki Bob to the Moon Shot & Bowl Set - by Eric October - Tiki Mug.” Mytiki.life, 18 May 2022.

Weibel, Deana L. “The Overview Effect and the Ultraview Effect: How Extreme Experiences in/of Outer Space Influence Religious Beliefs in Astronauts.” Religions, vol. 11, no. 8, 2020, p. 418.

Weisgall, Jonathan M. Operation Crossroads: The Atomic Tests at Bikini Atoll. Naval Institute Press, 1994.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.