Aiming too high: the Advent military communications satelliteby Dwayne A. Day

|

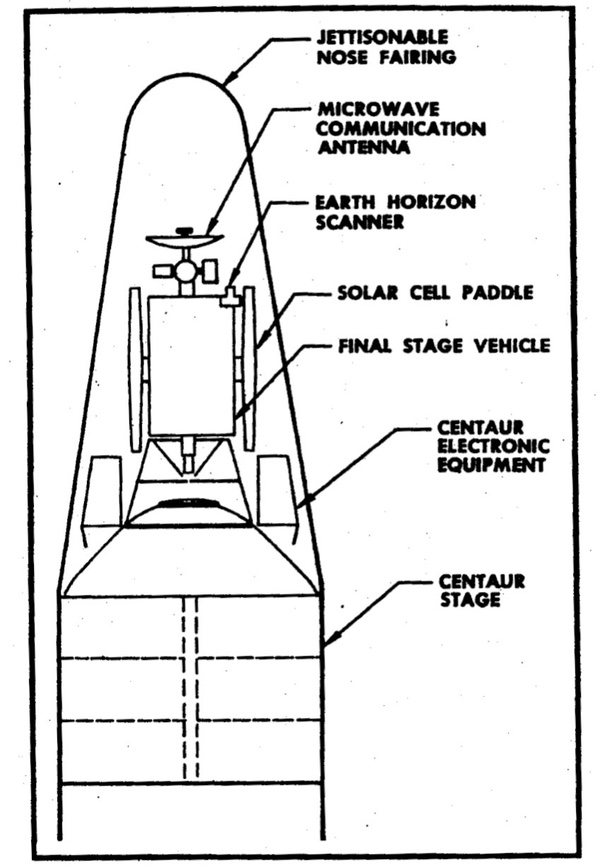

A 1960 drawing from an Advanced Research Projects Agency report showing Advent in its payload shroud atop an Atlas Centaur launch vehicle. Advent was too heavy for other vehicles. The Centaur upper stage, which used liquid hydrogen as fuel, was a major new technology development. It was being overseen by NASA, not the military. (credit: Advanced Research Projects Agency) |

Advent was started in the early years after Sputnik, when the United States had barely reached low Earth orbit. It was incredibly ambitious for its time. When most other American satellite programs were relatively lightweight and aimed at orbits less than a few hundred kilometers high, the plan for Advent involved placing multiple, large, three-axis stabilized, heavy spacecraft in geosynchronous orbit, 35,786 kilometers above the Equator. Advent soon succumbed to its own lofty goals, falling behind schedule and ballooning in cost. It also suffered from a complicated management structure and nascent interservice rivalry.

| Despite its name, Advent proved to be a dead-end in terms of technology, goals, and ambitions for military satellite communications. |

In May 1958, the Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) created a communications satellite committee to determine military planning for future communications satellites. By October 1958, the same month that NASA began operations, the first meetings of the committee led to the development of the technical plan that became Advent.[1] John R. Pierce of Bell Labs served on the ARPA panel. One of the briefings he received depicted a soldier using a handheld terminal for communicating through a geostationary communications satellite. Pierce became concerned that the military had no knowledge of the state of art technology in communications. His alarm proved prescient, because the program that the military soon began was a fantasy.[2]

By December, the Air Force and the Army Signal Corps had agreed on a development plan for future military communications satellites. A formal development program was started in January 1959.[3] ARPA described its satellite communications efforts as part of Project NOTUS, separating them into “delayed repeater” satellites such as Courier that recorded and then re-transmitted their signals, and “instantaneous repeater” projects that directly relayed communications. By May 1959, this plan had evolved into three projects. Strategic Air Command (SAC) wanted a polar-orbiting satellite named Steer, to be followed by an advanced system named Tackle. There would also be a geostationary satellite named Decree.

Steer was to consist of four communications satellites in polar orbit, enabling instantaneous communications between ground stations in the United States and SAC aircraft flying in the polar regions. By June 1959, three launches were planned for late 1960. Air Force Ballistic Missile Division was given responsibility for developing all aspects of Steer, with the Wright Air Development Division given responsibility for development of the communications subsystem.

Tackle was also planned to involve four satellites in six-hour polar orbits. Tackle was to test more advanced systems such as satellite station-keeping, attitude and control, and microwave communications. Three launches were scheduled for the last half of 1961 leading into early 1962. By the end of 1959, Tackle was described as “an interim program to use Steer-developed test bed for the early development and testing of components to be used in Project Decree.”[4]

Decree was initially planned to include seven satellites in geosynchronous orbit, with launches starting in early 1962. The communications subsystems for both Tackle and Decree were to be developed by the US Army Signal Research and Development Laboratory.

In August 1959 study contracts went to General Electric for the spacecraft ($5.5 million) and Bendix for the communications system ($8.5 million). Hughes Aircraft Company—which was then interested in developing communications satellites—was apparently aware of the project. But an internal Hughes memo in 1959 expressed the view that Hughes should concentrate on building a commercial communications satellite, which they believed they could do quickly and without government funds, although this would demonstrate “the inefficiency of military satellite programs.” That memo also proved prophetic.[5] In 1960 the main Advent contracts were issued to GE and Bendix. Hughes was also informed about the request for proposals to bid on the project, but it is unclear if they submitted their own bid.[6]

| But an internal Hughes memo in 1959 expressed the view that Hughes should concentrate on building a commercial communications satellite, which they believed they could do quickly and without government funds, although this would demonstrate “the inefficiency of military satellite programs.” That memo also proved prophetic. |

By February 1960, the three projects were reorganized to form Project Advent. Steer and Tackle were canceled, and Decree’s objectives were molded into the Advent objectives. ARPA’s description of Advent incorporated aspects of the earlier projects, noting “the ultimate objective of this project is the provision of global communications on a real-time basis at microwave frequencies with a high channel wide bandwidth capacity, and to provide an ultra high frequency polar capability for SAC as a by-product.” Fourteen flights were scheduled for 1961–1963, starting with four launches into 10,371-kilometer polar orbits.[7] This represented a shift in emphasis. Whereas Steer was initially intended to be an operational program serving SAC’s requirements, now there would be precursor Advent test missions that would presumably have some value to SAC, but were primarily developmental in nature. Advent was supposed to be the operational system, although it would have little value to Strategic Air Command because it required large, fixed, ground stations and SAC was interested in communicating with mobile terminals on aircraft.

By September 1960, overall management control for Advent was transferred from ARPA to the Department of the Army, not the Air Force. The Army was responsible for funding and for overall systems engineering. The Air Force was given a supporting role for the project.[8]

Advent was to be a multi-channel satellite with wide-band capacity for a large volume of communications. It was to have anti-jamming capability and a lifetime of one year. The plan was to be able to place a satellite anywhere along the Equator to communicate with American military forces overseas.

An early decision about Advent’s communications system played a major role in its later problems. Designers chose to use triodes in the communications system, rejecting traveling wave tubes as too unreliable. Triodes used more electricity than traveling wave tubes, and this drove the requirement for larger solar panels, which in turn drove the size of the satellite. As Advent continued development throughout 1961, traveling wave tubes improved, but Advent was locked into a decision to use triodes.

The Department of the Army was responsible for overall research and development on Advent, creating the U.S. Army Advent Management Agency at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. The Air Force Space Systems Division was responsible for systems engineering, development of the booster, and satellite tracking and telemetry. Systems engineering for the communications subsystem and its ground station was the responsibility of the U.S. Army Signal Research and Development Laboratory. Ground stations would have 18-meter diameter dish antennas. The U.S. Navy was also involved in developing a shipborne communications terminal.

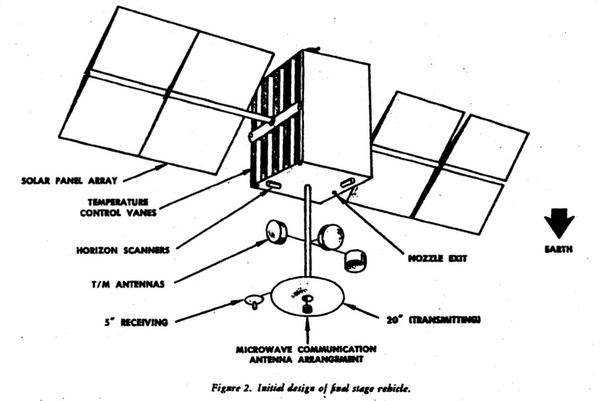

Advent was to have a horn antenna for receiving signals and a parabolic antenna for relaying signals to Earth. It would have four one-way radio-frequency channels (in other words, two two-way channels) and a rate of half a million bits per second on each RF channel. It would broadcast at a power level of one watt per RF channel.[9] In addition to the main communications antennas, the satellite would have crossed dipole antennas for telemetry, tracking, and command. The satellite mass would be at least 454 kilogram, which at that time counted as a heavy satellite even in low Earth orbit.

The satellite would have two solar power panels generating 600 watts. It would also be equipped with a battery to deal with times when the satellite was eclipsed by the sun. To keep it properly pointed, the satellite would have infrared horizon sensors and sun sensors. It would have “motor-driven inertia wheels” and a cold nitrogen gas propulsion system with nozzles mounted on the satellite body.

Because of its size, Advent required a more powerful rocket than the Air Force then had under development, so NASA was tapped to provide its ambitious hydrogen-fueled Centaur upper stage atop an Atlas first stage rocket. The program therefore required coordination among many different organizations.

NASA’s Centaur was a new and unprecedented project, unlike any rocket in development by the military. It was a high-energy rocket upper stage using liquid hydrogen as fuel. Liquid hydrogen was difficult to handle and its physical properties and behavior, particularly in a space environment, were not well understood. Centaur development had been assigned to NASA in 1959. That year the agency decided to launch its Mariner planetary spacecraft atop Atlas-Centaur rockets. Advent presented a more difficult set of requirements for the rocket stage than Mariner, which would essentially launch on an interplanetary trajectory without coasting in Earth orbit. Mariner’s trajectory did not require storing propellants in Centaur’s tanks for long, and because it was heading away from the Earth, the Sun would heat the Centaur from only one direction. In contrast, for Advent the Centaur would stay in Earth orbit. The toughest Advent requirement was to restart Centaur’s engines twice after two coast periods in Earth orbit. This meant that the Centaur had to maintain its liquid oxygen and hydrogen in partially filled tanks while the Sun, and sunlight reflected off the Earth, could heat them up from changing directions.[10]

ARPA drawing of Advent in orbit. Advent was considerably more sophisticated and ambitious than other communications satellite proposals of the early 1960s. This was at a time when the United States had only launched a few dozen satellites into space. (credit: Advanced Research Projects Agency) |

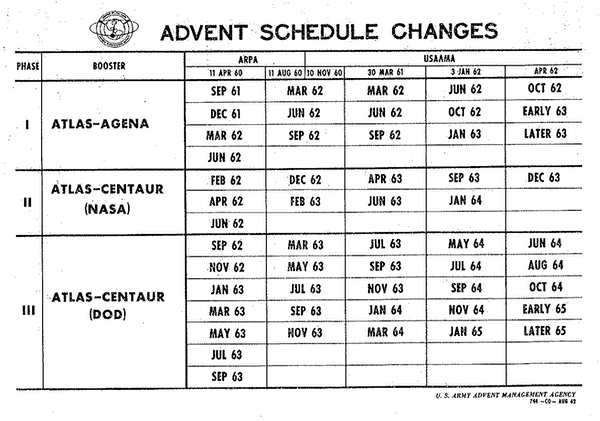

In August 1960, the phase one development plan was to fly three (previously four) low-altitude near-circular orbital flight tests using Atlas-Agena rockets. As of January 1961, these flights were planned to start by March 1962.[11] Phase two would follow in late 1962 with two direct injection launches of Advent satellites into geostationary orbit at about 105 degrees west using Atlas-Centaur launch vehicles. The plan was to conduct those tests in December 1962 and February 1963.

Those initial steps would be followed by the third and final phase, also using Atlas-Centaur. For that phase, the satellites would be placed in an intermediate orbit and then allowed to drift into their locations. The satellite would have a hot gas propulsion system to place the satellite into its final orbital location. The plan was for these flights to start by March 1963.

At some point phases 1 and 2 shifted and the plan was to carry prototype Advent hardware into low Earth orbit for phase 1, and to carry some prototype hardware—not actual satellites—as ride-along equipment on NASA Centaur test flights for phase 2.

Advent was under development at a time when all aspects of spaceflight were still relatively new and evolving rapidly. Like other projects, it was intimately linked to the rocket that would carry it into orbit, requiring greater payload capability than existed. As a result, payload requirements drove rocket development, but rocket shortfalls also posed a direct threat to Advent’s development. This was all complicated by the fact that NASA, and neither the Air Force nor Army, was developing Centaur.

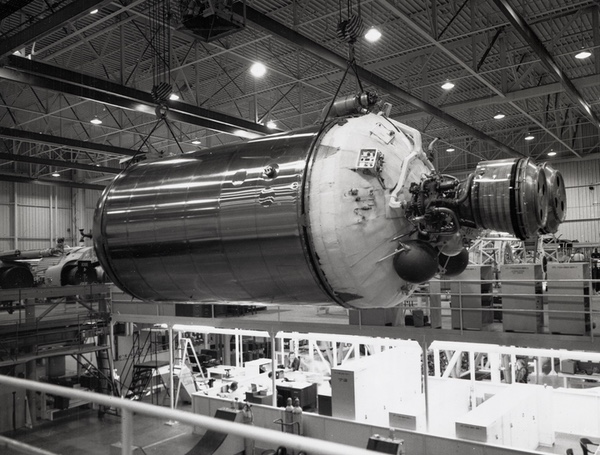

The Centaur upper stage during assembly at General Dynamics in 1962. Centaur was a NASA vehicle that was vital for the Advent mission. However, Advent's requirements were significantly greater than the NASA requirements for the Mariner and Surveyor spacecraft slated to use Centaur. (credit: Wikipedia) |

The requirements and the difficulty of using liquid hydrogen meant that Centaur development was experiencing problems from the start. It was becoming clear to military leadership by January 1961 that the Atlas-Centaur would be a major pacing issue. Pratt and Whitney was then working on development of the Centaur’s LR-119 engines. At a meeting early in the year it was apparent that the Centaur would have to provide increased performance to lift Advent, and Convair, which was developing the Centaur, proposed lengthening fuel and oxidizer tanks.[12]

In 1961, Centaur was also assigned as the launcher for NASA’s Surveyor lunar lander. Like Advent, Surveyor needed to restart the Centaur engines in flight. Now two major NASA missions—Mariner and Surveyor—needed the new and trouble-plagued rocket. But NASA could hold its two planetary missions to strict weight requirements whereas Advent’s weight was increasing—placing NASA in the difficult situation of having requirements set for Centaur by a program it did not control. Abe Silverstein, who was then director of NASA’s Lewis Research Center, wrote a memo to NASA Associate Administrator Robert Seamans in September 1961 declaring that Centaur had become “an emergency of major proportions,” and that NASA was “saddled with an improvement program which we don’t really need, one which will probably lower the reliability of the early NASA vehicles.”[13]

By summer 1961, the problems with Centaur were increasingly apparent even outside of NASA. In July, the Air Force Council wrote to the Air Force Chief of Staff about their assessment of the Air Force and the National Space Program. Acknowledging that Centaur was a NASA program, they wrote, “It is the Air Force view that Atlas-Centaur won’t do the job in the Advent program.” But they noted that DoD had directed no change in the Advent program until it had been re-studied.[14]

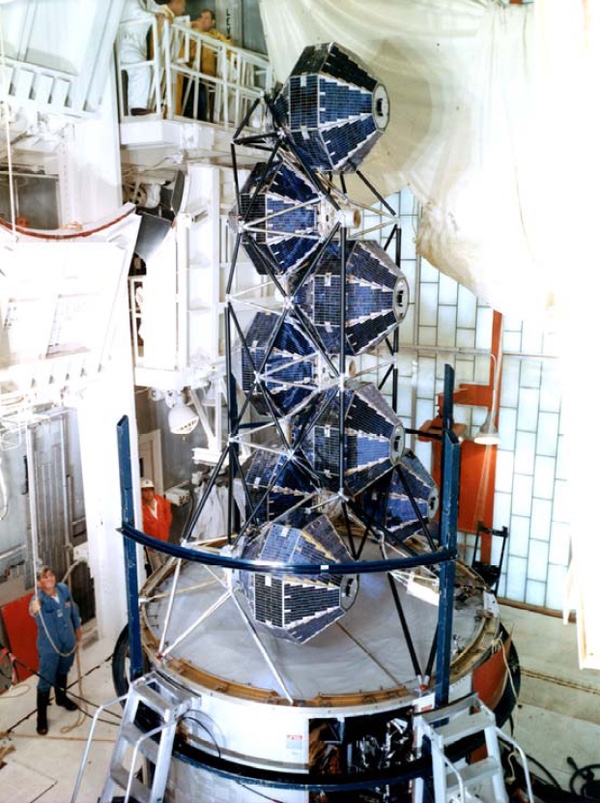

The Initial Defense Communications Satellite Program or IDCSP was the first stage of the Air Force’s military satellite communications capability. It involved placing multiple satellites in near-equatorial, sub-synchronous orbits. IDCSP was the Air Force's communications satellite program that followed the cancellation of Advent. The satellites were considerably smaller and less capable than Advent, and because they moved around in the sky ground dishes had to move to keep track with them. Upon reaching operational status, it was renamed the Initial Defense Communications Satellite System or IDCSS. (credit: Wikipedia) |

Centaur was only part of the problem. By late 1961 the General Electric satellite schedule had slipped significantly and Advent was experiencing major problems in terms of reliability, mass growth, and increasing costs.[15] Only a few months after the start of the fiscal year 1962, the Advent budget already required a 58% increase in funding ($41.5 million).[16]

| Abe Silverstein, who was then director of NASA’s Lewis Research Center, wrote a memo to NASA Associate Administrator Robert Seamans in September 1961 declaring that Centaur had become “an emergency of major proportions,” and that NASA was “saddled with an improvement program which we don’t really need, one which will probably lower the reliability of the early NASA vehicles.” |

In December, Harold Brown, the Director of Defense Research and Engineering for the Department of Defense, wrote to the Secretary of the Army explaining that he was suggesting management changes to Advent to bring costs under control. Brown also requested that “the objectives and orientation of the overall program be reviewed carefully and redefined to relate the direction and level of R&D effort more realistically” in light of problems experienced with the Atlas-Agena and delays in the availability of the Atlas-Centaur rocket. “Particular emphasis should be given in this review to obtaining an acceptable level of confidence of successful operation of the satellite and its payload before the first orbital test is scheduled.”[17] As Brown explained it, he was ready to approve the reprogramming of a substantial amount of money to cover Advent development, but this money would come from other projects, requiring some difficult decisions.

A few weeks later, General Bernard Schriever, head of Air Force Systems Command, wrote to Air Force Chief of Staff General Curtis LeMay with his views on Advent.[18] LeMay had requested Schriever’s input, and Schriever’s reply was blunt and to the point: “It is my opinion the wrong program if our objective is to achieve a useful military satellite communication capability at an early date. It is also being carried out under extremely difficult management arrangements. This has been my view from the initiation of Advent under ARPA.” He told LeMay that the problem was not between the Air Force and Army, which he believed was a good relationship, it was the way the entire program had been established years earlier. Schriever wrote that two years earlier he had stated this to the head of ARPA, to no avail.

Schriever noted that the Centaur could not lift more than about 272 kilograms into the required orbit at a time when Advent’s 453-kilogram weight was growing. Centaur was also slipping in schedule. He added that using a Titan III instead of a Centaur would not provide the required geosynchronous capability before 1965.

Schriever suggested that there were several alternatives, including using the Atlas-Agena rocket to provide a medium altitude orbit capability by July 1962, with an operational system demonstrated in early 1964. Schriever also suggested taking advantage of work already done on commercial communications satellites. He stated that a 41-kilogram military version of the satellite could be launched in groups of nine in “pseudo random polar 5,000 mile [9,260 kilometer] orbits,” providing an operational system in mid-1963.

Schriever believed that the Air Force should immediately begin development of an advanced military active communication system using the Titan III rocket. It could be launched first in 1965, reaching full operational capability in 1966. The satellites would also be in polar 11,112 kilometer orbits. “Although it is clear that twenty-four hour orbital satellites have useful characteristics, the studies to date by Aerospace [Corporation] indicate that an advanced military communications system should probably be a medium altitude solution with a large number of satellites to make neutralization uneconomical.” By “neutralization,” Schriever meant attack by the Soviet Union.

A week after sending his blunt letter to LeMay, Schriever followed it with a slightly-less blunt letter, this time commenting on Harold Brown’s proposed management changes for Advent. He did not think that the changes would significantly improve the health of the program and would likely have the opposite effect by blurring some of the responsibilities of different organizations, notably ones under Schriever’s control such as the Aerospace Corporation. He finished by stating that the Advent problem could only be solved by “the establishment of clearly defined program objectives to be implemented within sound management and funding principles.”[19]

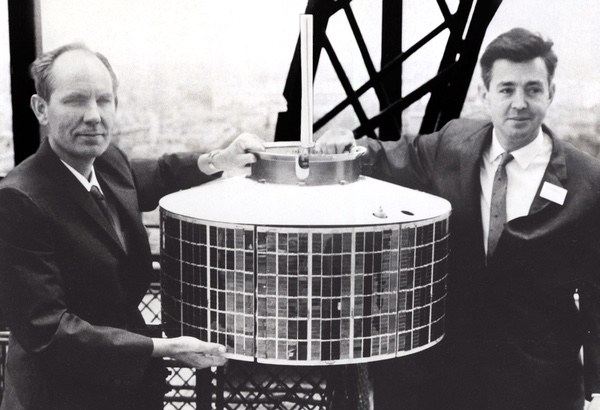

Syncom started as a NASA-sponsored experimental communications satellite in 1961. The satellites were manufactured by Hughes Aircraft Company. Syncom 1 was launched in February 1963 but failed soon after reaching orbit. Syncom 2 was successfully launched in July 1963. Members of Congress, as well as Department of Defense leadership, wondered if Syncom was capable of replacing Advent. But Syncom lacked many of the capabilities intended for Advent. Note Syncom's much smaller size compared to Advent. Syncom's mass was 68 kilograms compared to 454 kilograms for Advent.. (credit: Boeing) |

In February, an Army technical committee recommended that phases 2 and 3 be terminated and a lightweight satellite development program using the Atlas-Agena be pursued instead. The Army determined that the satellite vehicle was undergoing further schedule slippages. On April 17, 1962, the Army recommended terminating the phase 1 program.[20]

| At one hearing, Harold Brown told a congressional committee that Advent’s principal difficulty “was an attempt to rush into an experiment without having a payload which had any high assurance of working and in a circumstance where the booster that would finally put it into orbit was slipping.” |

In late May, the Secretary of Defense reoriented the Advent program, giving the Air Force responsibility for the space vehicle, communications payloads, boosters, upper stages, and injection into orbit. The Army retained responsibility for the communications ground equipment.[21] One goal of the restructuring was “to bring it into consonance with available boosters.” That reorientation was, for all intents and purposes, the end of the Advent program in terms of developing large geosynchronous satellites, although it officially continued, with new goals that had yet to be defined.

By summer 1962, Centaur had fallen two years behind schedule. This had affected when Advent flights could occur. But Advent was also experiencing substantial delays and cost increases of its own, which had prompted the DoD reorganization. Simply put, there was no clear indication of when Advent would be ready even if Centaur became available to carry it.

By summer 1962, several congressional hearings were called to investigate the problems of both Centaur and Advent. At one hearing, Harold Brown told a congressional committee that Advent’s principal difficulty “was an attempt to rush into an experiment without having a payload which had any high assurance of working and in a circumstance where the booster that would finally put it into orbit was slipping.” Brown added that it would have cost $300 to $500 million for two satellite systems, an enormous sum at the time, roughly equivalent to $2.7 to $4.6 billion in 2021 dollars.[22]

After a congressional hearing into the problems with Centaur, a follow-up hearing was called to dig deeper into Advent’s problems, and to determine if Advent would duplicate NASA’s Relay and Syncom communications satellite programs. At the hearing, Army and Air Force representatives revealed that Advent had undergone a substantial reorientation in the previous months.

According to Assistant Secretary of the Army for Research and Development Finn J. Larsen, by late 1961 it had become clear both that the Centaur had major problems and that General Electric’s delivery schedule for Advent had slipped substantially.[23] Centaur’s problems had not caused Advent’s problems, but they had certainly highlighted that it was not going to be possible to make Advent work. For phase 2 the Army’s payloads were going to ride along on NASA test flights of the Centaur vehicle. Because NASA would instrument the Centaur during these development flights, it would not carry as much payload as the Army wanted.[24]

Larsen stated that on April 17, 1962, the Army recommended to Deputy Director of Defense for Research and Engineering (DDR&E) Harold Brown and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara that the phase 1 program be terminated.[25] According to Larsen, the Army did not receive a reply to its recommendation. On May 21, the Secretary of the Army repeated the earlier recommendations to the Secretary of Defense, and on May 23 McNamara “reoriented” the Advent program, taking it away from the Army.[26]

The revised plan was for a lightweight satellite that benefited from improvements in stabilization techniques and lightweight traveling wave tubes, bringing the weight down to around 226 kilograms with about the same performance of the earlier planned satellite. This could be placed in geosynchronous orbit by an Atlas-Agena instead of the problem-plagued Centaur.[27]

One point of contention was Advent’s weight. John H. Rubel, the Assistant Secretary of Defense and Deputy Director of Defense, Research and Engineering, stated that in September 1960 the weight for Advent “was almost exactly 1,250 pounds.” But published sources claimed that by summer 1962, Advent had grown from 454 to 590 kilograms (1,000 to 1,300 pounds).[28] As Rubel explained, a “stripped down” version that was supposed to fly on early Atlas-Centaur launches was planned to weigh 454 kilograms, but the operational vehicle was 567 kilograms, far in excess of what Atlas-Centaur could lift.[29]

A key question concerned the choice of electronics for the communications payload and when the military should have switched technologies. With triodes, the satellite required 80 to 85 watts to perform its mission. With traveling wave tubes instead of triodes, the power requirement could be reduced to 30 watts. That translated into fewer batteries, fewer solar cells, and subsequently significantly lower mass for the satellite, possibly cutting the mass more than half.[30]

The decision to use triodes had not been made without careful deliberation. When Advent was first approved, one of the major concerns to engineers was about its reliability. At the time, program managers decided that traveling wave tubes had not proven their reliability and instead they selected triodes, which were believed to have proven reliability. While Advent was underway, on July 1, 1961, the Army had awarded a contract for development of a reliable traveling wave tube, but the Advent design was already too far along to change.[31]

By summer 1962, new traveling wave tubes provided extremely broadband performance and used less power than conventional tubes, which resulted in a smaller power supply. They had been specifically designed for the space environment and were available from several different companies. They were planned for testing in Telstar and Relay satellites then scheduled for launch later that year. But traveling wave tubes that had recently become available for space use were not yet capable of the higher frequency bands needed for Advent. Hughes, Lockheed, Space Technology Laboratories, and General Electric had all apparently submitted unsolicited proposals to the Air Force’s Space Systems Division to build a new lightweight Advent geosynchronous satellite, presumably based upon traveling wave tubes. It is unclear if their proposals would have met the original Advent requirements. Philco and RCA had proposed medium-altitude satellite designs.[32]

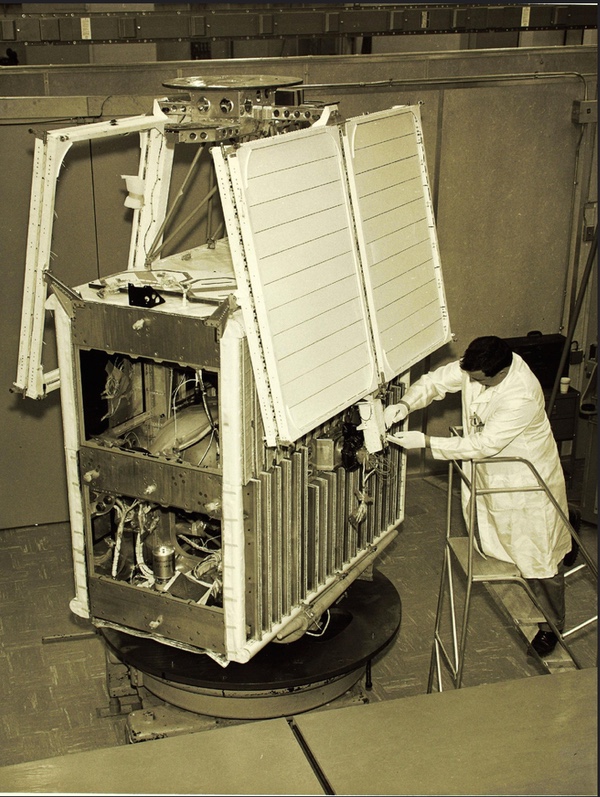

The engineering test vehicle under construction at General Electric. Cancellation of the program resulted in 10% of the company's satellite engineering workforce losing their jobs. (credit: San Diego Air and Space Museum) |

Brigadier General J. Wilson Johnston, commanding officer of the US Army Advent Management Agency, testified that when the Army took over the program in late 1960 it was apparent that the program had been severely underfunded considering its original objective.[33]

The members of Congress wanted to know if Advent was an obsolete piece of equipment. Larsen responded, “I think the telephone is an obsolete piece of equipment in one sense, but it is in daily use.” The Advent satellite may have been using older technology, but it would still be practical to use it.[34] When pressed further, Larsen said, “Advent was obsolete only in weight. In function, the older, heavier design would have done everything that a new, lighter system could.”[35]

| The members of Congress wanted to know if Advent was an obsolete piece of equipment. Larsen responded, “I think the telephone is an obsolete piece of equipment in one sense, but it is in daily use.” |

When asked if a Telstar satellite, which was developed for commercial use, could perform the military mission, Larsen disagreed, noting that there were military missions that required unique capabilities. Larsen also stated that if Advent referred to the heavy satellite, then Advent had been canceled, although technically the name “Advent” still referred to a military geosynchronous satellite communications development program.[36]

Congressman Joseph E. Karth, chairman of the House Subcommittee on Space Sciences, Committee on Science and Astronautics, was concerned that Advent had been allowed to continue even after the Army had recommended termination in February. He also wanted to know how much money had been spent between the February termination recommendation and May 23, when Secretary of Defense McNamara finally announced the decision.[37]

Had the program continued on its pace as of February 1962, the Army believed the satellite would have been ready to fly in April 1963.[38] Brigadier General J. Wilson Johnston was not happy that the Army no longer controlled development of the communications package on the satellite.[39] Advent was the Army’s major space program, and Army leaders apparently fought the reorganization, arguing that it made more sense to centralize authority for the program than disperse it.[40]

At the time, General Electric along with Bendix were about to submit the first non-flyable Advent prototype and possibly the first flight model to the Air Force for test and evaluation. Further work had been halted and General Electric had laid off approximately 1,100 employees at its missile and space vehicle department, about 10% of the total workforce.[41]

General Bernard Schriever testified after the Army representatives. He was not overly critical of the Army and laid some of the blame for Advent’s managerial problems on ARPA decisions made before the Army and Air Force were given control of the program—the same argument Schriever had made to LeMay in January.

Schriever noted that the Air Force was the largest user of long-distance communications and that a satellite communications system was vital to the Air Force’s strategic and tactical operations.[42] Schriever indicated that the Air Force’s current goal was a “minimum essential satellite system to be initially operational in late 1964.” It would consist of “a series of ultrasimple, high-reliability microwave repeater satellites in medium-altitude—5,000 miles [8,000 kilometers]—circular polar orbits.”[43]

During his congressional testimony, Schriever was asked if the problems with NASA’s Centaur were the primary cause of Advent’s troubles. Schriever thought that the problems with Centaur were a contributing factor to Advent’s problems, but not a primary one. He noted that phase 1 did not require Centaur, and phase 1 was also experiencing problems.[44]

“The big problem in the synchronous orbit satellite is to get the spacecraft to function properly in this environment,” Schriever explained. He added that the major challenges were the reliability of the overall system as well as the attitude control system. He predicted that the early satellites would last between one to three months.[45]

The congressional representatives were particularly interested in the management of the program and how that affected its problems. Schriever believed that technical issues were of greater importance than the program’s management and the Air Force and Army had mostly resolved their management issues. According to Schriever, Advent’s goals were too ambitious and beyond the capabilities of the fledgling space program.[46]

Chairman Karth wanted to know when the problems were detected and why they had not been addressed immediately, when significant money could have been saved. Schriever did not directly answer, apparently unwilling to get involved in a blame game that could get him and his service in trouble with senior Pentagon leadership.[47]

Schriever stated that because both the Army and Air Force had interests in Advent, there was inevitably a question of where to establish the program interface between the two services. Schriever believed that it made more sense to have the Army only in charge of the communications system than the entire satellite, because the operation of the satellite was linked with many other things the Air Force was already responsible for, like the booster and tracking and control of the satellite. His statement was an implicit criticism of the program management that had been established two years earlier.[48]

Schriever spoke highly of General Electric, but believed that the company was overly optimistic about what could be done within the schedule. In particular, he noted that the spacecraft stabilization system ran into problems when it was being tested in a vacuum chamber.[49]

| General Schriever’s testimony indicated that he currently viewed Advent as an R&D project. “It did not have an operational system as its objective. The main objective of Advent was to prove out certain capabilities.” |

Schriever also disagreed that the money spent on Advent had been for naught. The military still had substantial infrastructure like the ground stations that could be applied to other programs. But even the money spent on the satellite was not lost. “I feel that not nearly as much is down the drain as one might suppose,” Schriever testified. “Because the thing that you can’t measure, particularly in the spacecraft, is how much we got out of the project in terms of design, reliability development, environmental testing, and in test facilities.”[50]

General Schriever’s testimony indicated that he currently viewed Advent as an R&D project. “It did not have an operational system as its objective. The main objective of Advent was to prove out certain capabilities.”[51] Schriever was apparently referring to Advent as it then existed after the reorganization and cancellation of the primary contract. Prior to that, DoD and Army officials considered Advent an operational program. Indeed, some of Advent’s problems stemmed from the fact that the Army was doing R&D as part of an operational program rather than separately. This was further aggravated by the effort to shoehorn operational payloads onto Centaur development flights that needed their own special instrumentation.

DoD officials admitted that there were conflicting figures for how much it would cost to complete Advent as then-conceived—General Electric indicated $130 million was needed, Air Force Space Systems put the figure at $144 million, and the Director of Defense Research and Engineering believed that if the system had continued without being reoriented, GE’s cost would have been at least $180 million.[52]

Advent's schedule constantly slipped. The program was initially conceived as having three phases, with phase III involving placing satellites in geosynchronous orbit. (credit: Congressional report) |

At the hearing, congressional, military, and NASA officials engaged in substantial discussions about the future development and requirements for military satellite communications. Members of Congress wanted to know if the NASA-sponsored Telstar satellite that had been launched to a medium orbit in July would be useful to the military—the Air Force was gathering information on the flight, but Telstar was not a prototype satellite that the Air Force could turn into an operational system.

Members of Congress were also interested to know if the NASA-sponsored Syncom geosynchronous satellite due for launch the following year would be a sufficient replacement for Advent. (Syncom 1 launched in early 1963.) The Department of Defense was interested in Syncom and was funding work on mobile and fixed ground stations to test Syncom when it reached orbit. But Syncom was also not a prototype for an operational satellite. It had capabilities different than what the military wanted. It would provide valuable information and experience, but the Air Force would still need to develop its own system. Schriever indicated that when commercial communications satellites were operational, the military would certainly lease their services just as it used commercial telephone lines. But Schriever emphasized that Syncom did not have the necessary anti-jamming capabilities to perform the most important military missions.[53] He believed that it would be possible to have an operational military satellite communications system with the requisite capabilities by late 1964 or early 1965.[54]

During his congressional testimony in August 1962, Deputy Director of Defense, Research and Engineering John H. Rubel tried to explain when problems had first become apparent, what the Department of Defense had tried to do about them, and why it had not completely abandoned the Advent design a year earlier. One of the issues was that defining the management approach for Advent had taken time. “We had a lot of trouble getting the management arrangements established even the way they are,” he explained. When cost overruns became apparent in the fall of 1961 “we issued directives which placed ceilings on expenditure rates, which asked for modified plans in accordance with those guidelines, but what we did not do was cancel the project, or start a new project, or reorient the project, until we thoroughly understood what we were doing—or hopefully thoroughly understood what we were doing.” Rubel added that there was much disagreement within the military about what to do. “You would have had as many different courses of actions as you had people recommending them at that time.”[55]

Rubel acknowledged that the people designing satellites and launch vehicles for geosynchronous orbit had also come to a recent conclusion. “All of us have begun to appreciate much more keenly, in the last six months especially, that any of these launch vehicles… has got to have some kind of injection stage on top of it to make it really successful.” The third burn requirement for the Centaur had proved to be a major hurdle. “That is where you get into so much trouble,” Rubel explained.[56]

Rubel conceded that it was difficult to determine when a project was in such dire straits that it could not be solved and should be canceled. “We also have succumbed to a natural human tendency to solve first the problems that we understand best and to solve last—or to leave to later solution—the problems that are toughest and that we understand least.” He gave the example of how they had built an operations control room without anything to operate. “We can make mistakes and have made them in the past,” he conceded.[57]

One of the additional difficulties, according to Rubel, was that the traveling wave tubes then under development for space use transmitted at 2,000 megacycles, and the military was going to need them to transmit at 8,000 megacycles to operate in the frequencies the military used. They had also looked at ways of stripping down the satellite by reducing requirements such as the number of communications channels. But that ultimately had little impact on the satellite mass because of the use of triodes for transmission, and it would not have saved much money.[58]

The members of Congress who were asking Rubel questions seemed to soften as he explained the travails of trying to manage the program. They granted that these programs were complex. Rubel recounted how both the Advent and Centaur program managers had been “deputized” to work together to answer the issue of whether their approach was obsolete. “They told us on August 3, 1961, that everything was okay, they were both satisfied… About one month later we found out everything was not okay.” Rubel added “They were not trying to mislead us. They were conscientious and competent men, doing the best they knew how, and this is true of everybody working on the program.”[59]

| Rubel conceded that it was difficult to determine when a project was in such dire straits that it could not be solved and should be canceled. “We also have succumbed to a natural human tendency to solve first the problems that we understand best and to solve last—or to leave to later solution—the problems that are toughest and that we understand least.” |

Rubel then gave testimony to the newness of the space age: “We are working in new fields, without much past experience to guide us and the best people in the country will make misjudgments from time to time. Retrospectively, maybe Bob Seamans and I should have decided in April or May or June or July or August of 1961 that the time had come to cut this thing off. Maybe had we done so it would appear today retrospectively to have been a terrific decision. But neither of us were smart enough to see it that way at the time. At least I was not. I don’t think if I had to do it over again, without benefit of this 20/20 hindsight that I have today, that I would be smart enough to figure out by myself, especially, and not with the best advice and intensive investigation we do get by people up and down the line and independent agencies giving us the same answer.”[60]

Advent’s status was murky for the remainder of the year. Although officially a lightweight geosynchronous satellite remained a goal for the Department of Defense, the primary official in charge, General Bernard Schriever, was opposed to that approach and preferred a constellation of smaller satellites in lower orbits. By the end of 1962, the lightweight geosynchronous satellite was still only a study, and Schriever was pushing his own solution. The revised program—and the major focus for the Air Force following the reorientation—was to launch 24–36 medium-altitude satellites.[61]

Despite the substantial reorganization, by fall Congress was not convinced that Advent—or whatever they believed Advent was at that time—was on the right path. By September and October 1962 hearings, some members of Congress indicated that the program could not be justified. A report from the applications, tracking and data acquisition subcommittee of the House space committee stated: “To develop a new satellite vehicle when the Relay, Telstar and Syncom satellite vehicles would be available with modification (except for transmitting tube of proper frequency) appears to be disregarding the development that has been carried out by others.” General Schriever informed Congress that the low altitude satellite system he preferred could be operational by late 1964 or early 1965. But the House subcommittee noted that Hughes had indicated that a nine-satellite geosynchronous system could be operational about a year after the Air Force’s low-altitude system.[62]

In November, the House space subcommittee issued a report stating that there was “little or no evidence of a spirit of cooperation between the Army and the Air Force in the Advent program,” adding that “the nation has very little to show” for the $170 million spent on Advent to date—the equivalent of over $1.5 billion today. The report also criticized DDR&E Harold Brown, stating that he “might have supervised the Advent project more closely.”[63]

“The subcommittee rejects the idea that it is impossible for two or more military services, or civilian agencies of the government, to work effectively and harmoniously on a particular development program. Clearly a single manager endowed with both responsibility and authority is the most effective management organization, and this was lacking in Project Advent,” the report said.[64]

| Advent has been largely overlooked in official and popular histories of the early space program, primarily because it never flew. But in terms of cost and ambition, it was a major military satellite program and an early harbinger of the death spiral that future space projects would experience. |

In January 1962, General Schriever had indicated to Air Force Chief of Staff General Curtis LeMay that Air Force cooperation with the Army was good at that time. The House space subcommittee report in November implied that cooperation had deteriorated substantially since the Air Force had taken the lead. It noted that the Air Force had canceled a contract with Space Technology Laboratories for technical guidance as soon as the Army signed a contract with the company for the same kind of guidance. The Air Force signed a new contract with Aerospace Corp. to cover the work previously performed by STL. The Air Force also refused to allow the Army to assign representatives to the General Electric facility where the Advent satellite was being developed. Collectively, the Air Force actions indicated that now that it was in control, the service was trying to freeze the Army out of Advent, presumably to kill the program once and for all.[65]

By December 1962, the lightweight geosynchronous satellite was still in limbo, with the Air Force making no moves to begin a formal procurement effort despite several companies already prepared to bid.[66] Air Force Systems Command’s Space Systems Division was planning to brief potential contractors on its random-orbit, medium-altitude communication satellite program, now designated Program 369. The Air Force was interested in a 9,260-kilometer altitude communication system which could involve as many as 20 satellites in random orbits at the same time. As many as five to seven satellites could be launched by a single Atlas-Agena D rocket. Communications capability could be restricted to one to four channels in the initial program.[67]

The Air Force effort to develop a replacement for the canceled Advent continued, eventually resulting in the Interim Defense Communication Satellite Program, or IDCSP.[68] After Philco won the competition to build a new series of satellites, in October 1963 Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara put the project on hold while the Pentagon negotiated over renting communications capability from the newly created Communications Satellite Corp. (Comsat). Negotiations dragged on until summer 1964 before they were suspended and the Air Force resumed work on the dedicated military communications program. In the latter half of 1964, the Pentagon tried to negotiate a “free ride” on experimental Titan III rocket launches rather than purchasing dedicated Titan III rockets after the launch vehicle was declared operational. The House of Representatives criticized the effort later that year as a “plan for short-range economics depending on a high-risk program that may prove costly in the end.”[69]

The original plan for the medium-altitude satellite program had an estimated cost of $60 million for the satellites and a total $165 million including ten Atlas-Agena launches. A modified approach, using a much higher orbit and fewer launches, cost $33 million. (The costs of Advent had grown from the original $140 million estimate to $325 million.)

In June 1966, the Air Force launched seven 45-kilogram communications satellites into near-synchronous orbits of 33,877 by 33,655 kilometers (an eighth satellite was a technology demonstrator). This was below Advent’s planned orbit and meant that the satellites would slowly move around the sky, requiring some movement of the ground antennas to keep track with them. The advantage of being in this non-synchronous orbit was that a failure of a satellite would not create a major coverage gap, only a temporary loss until another satellite moved into view. A second cluster of eight satellites was launched in August.[70]

It was three years late, but the Air Force finally had its communications satellite system.

Advent has been largely overlooked in official and popular histories of the early space program, primarily because it never flew. But in terms of cost and ambition, it was a major military satellite program and an early harbinger of the death spiral that future space projects would experience when they proved too expensive to pursue, and moved so slowly that they became obsolete before reaching orbit.

Advent remains somewhat of an enigma because the primary public source on the program—the 1962 congressional hearings—contains incomplete and somewhat contradictory information. Who was to blame for the program’s cost overruns: the Army, Air Force, General Electric, ARPA, or senior DoD leadership? Could the program have been reoriented earlier and turned into a useful project, or was it always too ambitious to be practical? Did Advent’s weight increase dramatically, or was its weight known early in the program and simply misreported? How did NASA respond to requirements that were being established by the DoD? When did General Schriever begin to push for an operational communications satellite system and how was that related to his views of Advent’s problems?

A bigger mystery about Advent is why military officials did not realize in 1961 that the satellite they were developing was far too heavy for the rocket to carry, and why they did not at that time choose to switch to the much more promising traveling wave tube technology that would have cut its weight at least in half. Perhaps a satellite even half Advent’s size would have run into its own development problems, but officials allowed Advent to drag on long after they should have realized its problems were insurmountable. Perhaps the answers to these questions are hidden in military document archives that have yet to be explored.

But perhaps the biggest mystery is why Advent was so ambitious from the start. The communications satellites that flew in the early-mid-1960s—Relay, Telstar, Syncom, IDSCS—were small compared to the bulky and heavy Advent. And as an indication of just how over-reaching Advent was, the first gyroscopically three-axis stabilized geostationary communications satellite, NASA’s ATS-6, was launched in May 1974, 12 years after the original goal for Advent. Advent was not the dawn of a new age of military geosynchronous communications satellites, but rather unfortunately, the beginning of a trend of unrealistic military space projects.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.