A mystery, wrapped in an enigma, surrounding an explosion: US intelligence collection and the 1960 Nedelin disasterby Dwayne A. Day

|

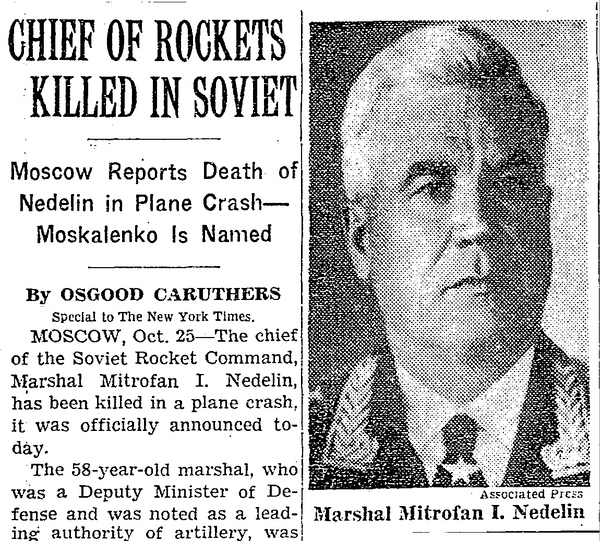

Nedelin's death was reported by the Soviet government soon after it occurred. They claimed he died in a plane crash. By December, an Italian news service linked his death to the explosion of a missile. (credit: New York Times) |

After the reported death, the CIA began to hear other stories about how Nedelin had died. One report was that Nedelin and other specialists were at a test site for a new nuclear engine for a missile. After the missile failed to launch, he and others left the underground shelter. The missile exploded unexpectedly, killing up to 300 military personnel and civilian scientists in the conflagration.

| After the missile failed to launch, he and others left the underground shelter. The missile exploded unexpectedly, killing up to 300 military personnel and civilian scientists in the conflagration. |

The CIA also received information from another informant indicating that Nedelin had died in an ICBM accident in September or October. The informant said that an aircraft factory had received an order for 60 or 70 aluminum caskets, supposedly for the victims of this accident. There were other reports of a large explosion in “Central Asia” in fall of 1960. In December 1960 the Italian Continentale News Agency had reported 100 people had been killed in a rocket explosion in the Soviet Union, a report that had been picked up by The New York Times.

In October 1965, an article about the 1960 event appeared in Britain’s The Guardian newspaper. The CIA was prompted to produce a top secret report summarizing what the agency knew about the event and its impact. |

In an October 1965 Top Secret “Special Report” produced by the CIA and titled “Soviet Missile Disaster in 1960,” the CIA stated “The substance of these reports appears valid, except that there is no evidence of any experimentation with nuclear propulsion.” The CIA had evidence—most likely communications intercepts—indicating that “there was a prolonged and unsuccessful attempt to launch an ICBM vehicle on 23 and 24 October 1960.”

Although many details remain classified, the CIA and the National Security Agency and other intelligence agencies have begun to release information indicating the scope and breadth of efforts to monitor various Soviet missile launch sites, notably the sprawling complex at Balkonur, which the CIA labeled the “Tyuratam Missile Test Range.” Monitoring facilities in Turkey and Iran, as well as aircraft that operated off the Soviet border, used various methods to detect the signals from Soviet missile and space launches. Often the monitoring sites had tipoffs that launches were about to occur, sometimes many hours in advance, which is how the monitoring aircraft were able to get into position. (See “Front line on the TELINT Cold War: The Tell Two missions collecting rocket and satellite telemetry during the 1960s,” The Space Review, February 21, 2022 and “Stealing secrets from the ether: missile and satellite telemetry interception during the Cold War,” The Space Review, January 17, 2022.) But in 1960, the US intelligence community’s ability to collect information on Soviet missile launches was still rudimentary.

The CIA also had another source of information that something had happened. The source is still deleted in the 1965 report, but “noted a possible explosion in the general area of the Aral Sea on 24 October 1960, shortly after the [deleted] launch time.” That source was probably either a system of seismic sensors or infrasound sensors which can detect loud noises in the atmosphere. Such sensors are still used today for intelligence purposes.

The CIA also detected a large influx of aircraft into the testing range facility after October 24. “During the week of the 25th, flights between Tyuratam and Dnepropetrovsk—location of a major ballistic missile producing facility—were at the highest level ever noted,” the report added.

| Using powers of deduction that would make Sherlock Holmes proud, in the final section headlined “Possible Consequences” the CIA analysts who wrote the 1965 report carefully eliminated the unlikely scenarios. |

The CIA had aerial photography of the area that indicated that by October 1960, there were two completed launch complexes at Baikonur and a third under construction. The photography also revealed something relevant about the two completed complexes: upon leaving the control bunkers, in order to reach the base, personnel would have to pass the launch pad. Any on-pad explosion that occurred while persons were leaving the bunkers “would almost certainly produce a large number of casualties.”

After the failed attempt in late October, “no further attempt was made to launch an ICBM from Tyuratam until twelve weeks later, in the middle of January 1961, when a first-generation ICBM was launched for the first time since July 1960,” the report stated. “Approximately six weeks after 24 October, an earth satellite vehicle was launched there,” it added. (The “first-generation ICBM” was the venerable R-7, which became the Soviet Union’s primary space launch vehicle for many years.)

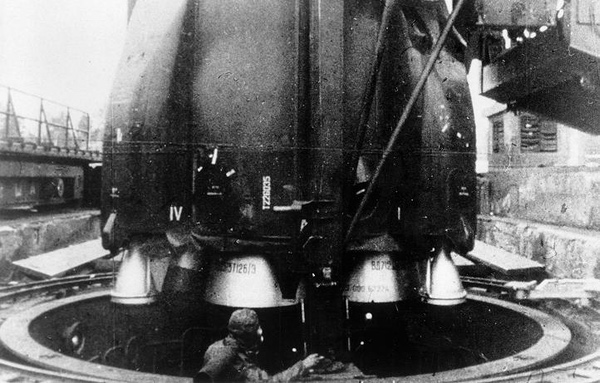

The first Soviet ICBM, the R-7, used kerosene and liquid oxygen, and required long preparation time before it could launch. It had only limited service as an ICBM, but was used to launch Sputnik, Yuri Gagarin, and its descendants are still in operation today launching satellites. The R-16 used storable propellants. (credit: FAS.org) |

Using powers of deduction that would make Sherlock Holmes proud, in the final section headlined “Possible Consequences” the CIA analysts who wrote the 1965 report carefully eliminated the unlikely scenarios: the launching difficulties and personnel traveling to Dnepropetrovsk probably ruled out an accident involving one of the “highly reliable ‘old’” type ICBMs—the type used to launch Sputnik. It also seemed unlikely that the problems involved only a new launch pad, because that could have been fixed quickly, rather than the four months it took to launch a new missile.

The report added that the next launch attempt of a new missile occurred on February 2, 1961, but resulted in failure. This was presumably the first of a missile that was then “fired intensively” at the range during 1961. Another new missile was fired at Baikonur in April 1961. Depending on whether the October 1960 attempt was the same missile as either the February or April 1961 missiles, it took the Soviets four or six months to fix the problems encountered in the October explosion. If the October explosion involved an entirely different missile, then “the difficulty has not been corrected yet,” five years later, the report stated.

The wreckage after the explosion of the R-16 ICBM. It took the Soviet Union several months to recover from the accident. The R-16 later entered service as an operational long-range ICBM. (source: Russian archival footage) |

Despite the inconclusiveness of the report’s conclusion, the report stated in a footnote that “The missile that exploded and killed Nedelin is believed to have been the first SS-7, a two-stage liquid-fueled ballistic missile which is now the Soviets’ most widely deployed ICBM.” That footnote was in fact correct, and the fiery accident involved an SS-7, designated the R-16 by the Soviet Union.

In December 1960, a Titan I ICBM blew up at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Despite creating a huge blast and subsequent wreckage, no one was hurt. (credit: USAF) |

In mid-October 1965, Britain’s The Guardian newspaper wrote about the 1960 disaster. The Guardian reported that Oleg Penkovsky, who had spied for the CIA until he was captured and executed, claimed that 300 people had died in the explosion. The article was picked up by The New York Times on October 17. Those articles almost certainly prompted the CIA to produce its internal top-secret reassessment of the explosion—informing senior American policymakers about what the agency knew after all this time.

| Unlike the low-key CIA report, the film showed that the explosion was as if the gates of hell had opened on a launch pad in Kazakhstan and consumed dozens of men in fury. |

The United States suffered many missile and rocket accidents in the 1950s and into the early 1960s, including ICBMs blowing up on their launch pads. In December 1960, only a few weeks after the explosion in Kazakhstan, a US Air Force Titan I ICBM blew up while being lowered into its silo at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Nobody was injured in that blast. The explosion created a massive pit that today is filled with brackish water and shattered concrete. But the US Air Force limited who could be near fueled rockets. In the Soviet Union, safety standards were far more lax.

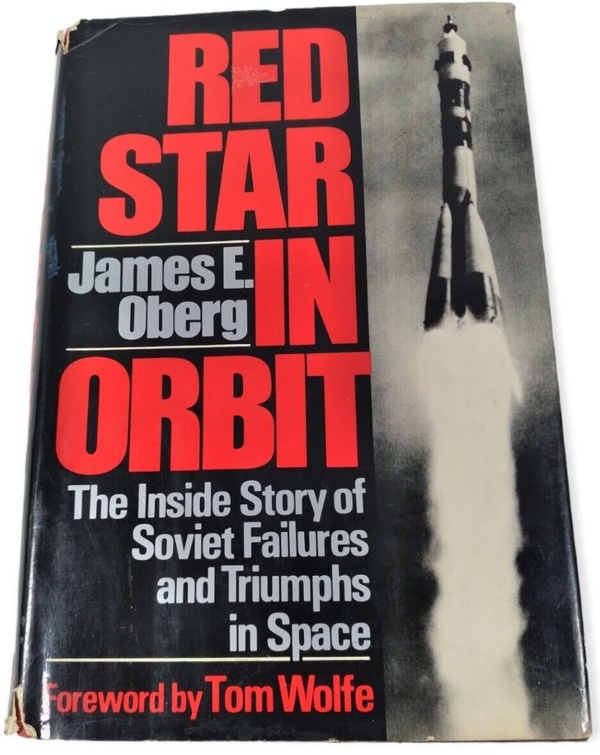

In 1981, James Oberg published Red Star in Orbit, which included a discussion of the October 1960 accident. Many details remained unknown at that time. Even today, the exact number of people killed is unclear, with estimates ranging from 60 to 150. |

The exact number of people killed in the Nedelin explosion remains unknown, and estimates range from 60 to 150 people. It took decades for any official confirmation to come out of the Soviet Union about the disaster, leading to much speculation in the West, most notably by Soviet space expert James Oberg in the 1980s. In the 1990s, Russia released horrific film footage of the explosion. Unlike the low-key CIA report, the film showed that the explosion was as if the gates of hell had opened on a launch pad in Kazakhstan and consumed dozens of men in fury.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.