Trends in NASA authorization legislationby Alex Eastman and Casey Dreier

|

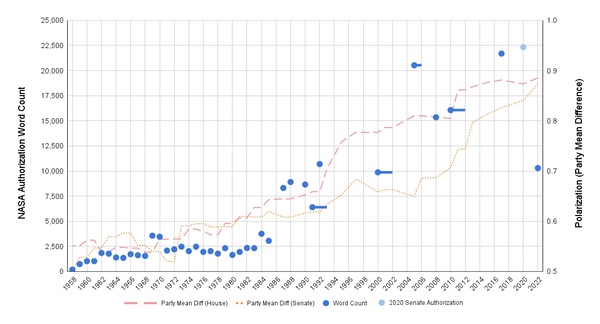

Chart 1. NASA Authorization legislation has, on average, grown in length and decreased in frequency beginning in the mid-1980s, consistent with the increasing polarization of Congress. Lines denote the duration of multi-year authorizations. The outlier in 2022 was the likely result of the NASA authorization’s inclusion within the CHIPS and Science Act. We present the 2020 NASA Authorization, which passed the Senate but not the House, as context. Note how legislative word count grows similarly with congressional polarization, as measured by UCLA’s DW-NOMINATE index. |

Congressional authorization legislation is required to “establish, continue, or modify federal programs” and is necessary for the legislative appropriation of funds from the US treasury. NASA authorizations also can establish national policy, new programs, and state findings and “senses of Congress” to guide the implementation of the US civil space program. And though authorizations can detail spending levels for various programs, they are distinct from appropriations, which must occur every year lest they result in an operational shutdown of agencies like NASA. Without an authorization, however, the US space program can function normally.

We had noted the relative dearth of modern authorizations and wondered: is our current pace of legislative action unique or consistent with historical trends?

| The year 1992 can be considered a turning point in the frequency of legislation: since then, there have only been six NASA authorizations signed into law. |

To measure this, we analyzed every NASA authorization ever signed into law. We recorded key policy highlights as they pertained to exploration, planetary science, the search for life, and planetary defense. And we measured both word counts and dates in which legislation were signed into law. Our full list (including source links and notes) is available at The Planetary Society.

Measuring word length is relatively straightforward for modern legislation (one merely highlights relevant sections of legislation and performs a word count), but NASA’s authorizations prior to 2000 exist only as scanned PDF files. We used Apple’s optical character recognition system built into iOS to select to copy out the relevant text from these PDF files. We acknowledge there will be some artifacts and inaccuracies in this process and that the exact word count may vary to a small degree using other approaches. However, we are confident that our analysis is accurate enough within the scope of our needs and given the relative scale (in the thousands to tens of thousands of words) of the source documents.

Between 1958 to 1985, Congress passed without fail annual NASA authorizations. Between 1986 and 1992, Congress passed annual NASA authorizations except for the notable years of 1986 and 1989. The first example of a multi-year authorization was signed into law in 1991, though it only specified NASA’s topline for two future years and was replaced by a new authorization the following year.

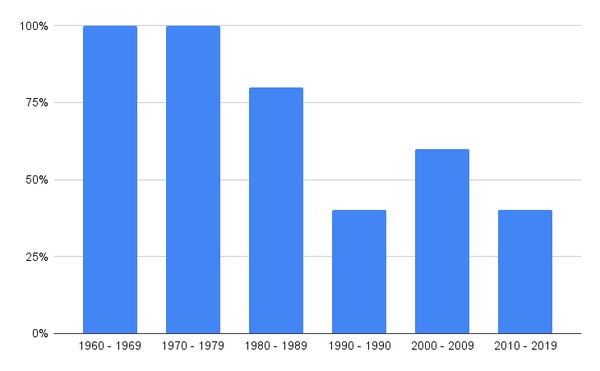

The year 1992 can be considered a turning point in the frequency of legislation: since then, there have only been six NASA authorizations signed into law. And though three of these were multi-year authorizations, the number of years NASA has gone without congressional authorization is much greater than in prior decades (Chart 2).

Chart 2. The percentage of a decade in which NASA appropriations were explicitly authorized. This chart takes into account the multi-year authorizations in the 1992, 2000, 2005, and 2010 acts. |

Regarding length, from 1958 to 1982, authorizations tended to be terse, around 1,900 words. Their focus was on line-item program authorizations. However, beginning in 1983 the average length began trending sharply upward, with the last standalone legislation clocking in at nearly 22,000 words in 2017 (Chart 3). The 2022 NASA authorization is a notable outlier, coming in at half the length of the previous legislation; we note that it was included within another bill and was likely pared down as a result. The 2020 standalone NASA Authorization, passed by the Senate but not the House, clocks in at 22,000 words and fits nicely on the modern our growth trendline.

Why the growth? One explanation is that NASA just does more than it used to. To some degree, this is true: NASA has grown to include sustained Earth science, biological and physical sciences, technology development, and planetary defense activities. It simultaneously manages a sustained human presence in low-Earth orbit while preparing for a return to the Moon. But we note that changes in NASA’s activities in the past do not correlate with legislative word count. 2005’s authorization, which kickstarted the Constellation program, is the second-longest legislation on record, but the start of the Space Shuttle program or the Vision for Space Exploration saw no similar bump in size. Similarly, NASA’s 1985 authorization dedicated just 109 words to the project that would become the International Space Station. Additionally, the most ambitious and rapid development period of NASA’s history—the Apollo era—regularly saw authorizations ten times smaller than modern legislation.

The nature of the authorizations has itself changed. In the annual legislation era through the 1980s, bills were mostly focused on line-item fiscal allotments. Modern legislation tends to be much more focused on policy issues, authorizing a handful of topline authorizing amounts equal to those already appropriated. The increase in policy prescriptiveness accounts for much of the content of the growth, though not necessarily the reasons behind it.

| Prior to 1994, Congress had missed just three authorizations over the previous 21 years. Since then, they have passed only six. |

We should note that the two largest relative increases in legislative length correlate with both Shuttle disasters. The NASA Authorization Act of 1988 is 171% (nearly three times) longer than the 1986 authorization passed prior to the loss of the Challenger. Similarly, there is a 107% increase in word count in the authorization following the Columbia orbiter’s breakup during reentry. But these are two discrete events and don’t necessarily support a trend.

Instead, we suggest that increasing political polarization is the primary driver of both the growth in length and infrequency of NASA authorizations.

Prior to 1994, Congress had missed just three authorizations over the previous 21 years. Since then, they have passed only six. Chart 1 demonstrates the suggestive correlation between increasing polarization in the US House and Senate as measured by UCLA’s DW-NOMINATE index and the growth in word length over time.

Polarization explains why legislation has become less frequent: it has led to gridlock and inaction in a broad sense. We believe it is no accident that the rate of legislation collapsed after the 1994 midterm elections, which ushered in our modern era of divided government where no party lays claim to Congress for very long.

The infrequency of NASA authorization legislation also likely feeds into its growth, as various constituencies fight to include their priorities when the stars align to pass one into law. It’s the political equivalent of how scientists will ornament once-in-a-lifetime flagship missions with dozens of instruments, bloating their cost: fewer legislative opportunities lead to more laden policy vehicles.

Ironically, this doesn’t mean that the politics around NASA itself have become more partisan: the space agency’s recent authorizations have passed by unanimous consent or by voice vote, which only occurs when there is functionally no opposition to the bill. Instead, the slow pace of authorizations is due to overall gridlock and the general departure from the regular order of Congress.

This puts NASA in a position where Congress will more or less leave it alone until they determine, somewhat arbitrarily, that it is time to shake things up. On the other hand, perhaps this approach hits a sweet spot wherein Congress gives enough direction to NASA to set precise objectives, but grants NASA enough freedom to accomplish them effectively. The coming Artemis missions make for a good proving ground to see if this is indeed the case.

The modern infrequency of NASA authorizations is indeed distinct from the first few decades of the space agency’s existence. Because NASA authorizations that do pass into law tend to do so with little opposition, this slowdown is almost certainly due to overall trends of political polarization, not polarization around NASA itself.

| The slow pace of authorizations is due to overall gridlock and the general departure from the regular order of Congress. |

As a consequence, NASA authorization acts have become less focused on spending and more focused on establishing programs, setting policy, requesting reports, and asserting findings and senses of Congress. This has resulted in an average increase in authorization length by a factor of ten since the 1980s.

The unpredictability of authorization legislation has effectively removed a regular check in the congressional funding process, reducing the influence of the authorizing committees and increasing the power of appropriators. We take no stand on if this is good or bad, but there is, ultimately, less consensus and less political buy-in from the lack of regular authorizations on NASA’s activities and programs. With the incoming Congress as polarized as ever, these trends show no signs of slowing down.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.