Russia returns to the Moon (maybe)by Dwayne A. Day

|

| Luna-24 brought back samples in 1976, and there have been no Soviet or Russian lunar missions since. Planetary missions became rare, and failures led to longer delays before the next mission. |

With so few missions beyond Earth orbit during the last 40 years, Russian scientists and engineers have very little experience. Since 1983, Russia and the former Soviet Union have launched eight planetary missions: Venera 15 and 16 in 1983, Vega 1 and 2 in 1984, Phobos 1 and 2 in 1988, Mars 96 in 1996, and Phobos-Grunt in 2011. Although the Vegas and Veneras were mostly successful (with one of the Vega landers setting down on Venus in 1985), after the mid-1980s their success record became terrible: Phobos 1 died in transit to Mars and Phobos 2 died soon after entering Martian orbit, and neither Mars 96 nor Phobos-Grunt even made it out of Earth orbit. There’s a clear and obvious trend in those missions—Russia’s last planetary mission was more than a decade ago, and it has not had a successful mission in more than three decades. Luna-25 has to face some grim statistics.

The Soviet Union’s Luna program had a long and glorious history, as detailed by space analyst Anatoly Zak and others. But the last mission, Luna-24, brought back samples in 1976, and there have been no Soviet or Russian lunar missions since. Planetary missions became rare, and failures led to longer delays before the next mission.

The 2011 Phobos-Grunt mission to one of Mars’ enigmatic moons was very ambitious and seemed doomed to fail, as this author predicted shortly before launch (see “Red moon around a red planet,” November 7, 2011). Surprisingly, it didn’t die at Mars, or even in transit to Mars, it died in Earth orbit. The Russian investigation blamed the failure on cosmic rays knocking out systems on the spacecraft, reminiscent of their more recent claims that micrometeorites took out the Soyuz and Progress spacecraft—it’s always an act of God, not an act of Russia. A logical decision at that point would have been to design a planetary program with some initial smaller goals to rebuild skills and knowledge lost in the decades since the collapse of the Soviet Union (see “Red planet blues,” The Space Review, November 28, 2011). That did not happen.

In 2011, just before the failure of Phobos-Grunt, the Russians laid out a mid-term “Russian Lunar Program” consisting of Luna-Resource in 2013, Luna-Glob in 2013–2014, a Luna-Rover mission in 2015 or later, to be followed by a Luna-Sample Return mission. Part of the goal of the sample return mission would be to develop techniques for returning future cryogenic samples from the Moon—in other words, keeping the volatiles frozen at or near their temperature when collected. The timeline was a total fantasy, and none of the spacecraft was even under construction despite launch dates only a few years away.

The Phobos-Grunt failure forced a reevaluation of the lunar plans (see “A Russian Moon?” The Space Review, January 28, 2013.) After Phobos-Grunt, Russia scaled back and canceled these lunar plans but would soon have to scale them back further. In early 2013, the Russian government announced plans to launch a lunar orbiter in 2015, followed by a lander a year later, both of them designated Luna-Glob. For at least a little while, it seemed as if Russia was adopting a more logical set of planetary science goals.

Then, for a time, nothing happened. And then for a longer time, nothing continued to happen, at least with the Russian lunar program. In the meantime, China was conducting an impressive series of lunar missions, with orbiters in 2007 and 2010 followed by landers—some equipped with rovers and eventually a sample return system—in 2013, 2018, and 2020.

The Russian 2015 lunar orbiter mission was never real: to meet that deadline it would have had to be already under construction in 2013 when the announcement was made. No lunar orbiter was ever built. Even though orbiters are easier to build than landers, the Russians decided to try a complicated lander going to a location no other vehicle had gone before.

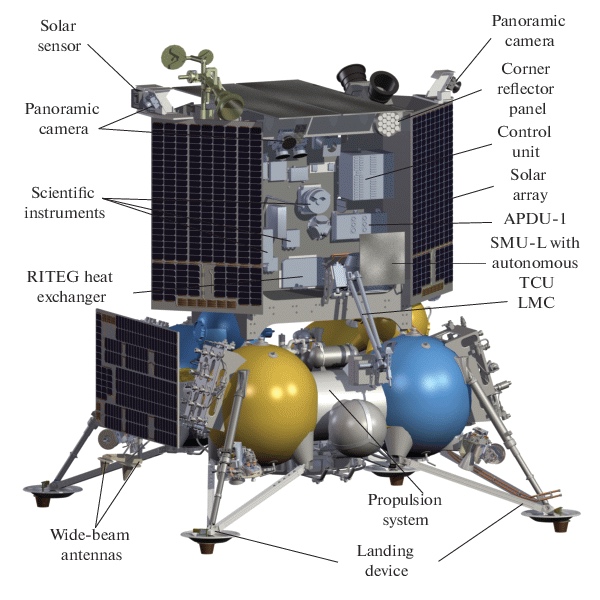

Luna-25 is a large and sophisticated spacecraft intended to land at the Moon's south pole. (credit: Lavochkin) |

Over the next decade, the lunar lander was assembled, but very slowly. It was designated Luna-25. Rather than a relatively simple lunar orbit mission to rebuild skills and capabilities, the Russians decided to go for broke, picking a lunar landing site that no other country had landed at before—the south pole—and equipping the spacecraft with a sampling arm and a suite of instruments to test soil samples. The descent module is to land near the Boguslawsky crater. Instruments will conduct chemical and spectral analysis of the surrounding area to try and locate lunar water. If the mission succeeds, it would be a major accomplishment. Reading between the lines, it was obvious that the Russians determined that they needed to fly a mission that was unique and impressive, not try to rebuild atrophied skills and capabilities.

| Reading between the lines, it was obvious that the Russians determined that they needed to fly a mission that was unique and impressive, not try to rebuild atrophied skills and capabilities. |

Russian space science policy has operated along somewhat schizophrenic lines. On the one hand, to get projects approved, they needed a foreign partner. On the other hand, to pursue Russian-only missions, they had to propose missions that were not something the Americans had already done, even if they lacked the skilled people and technology to make it work. For many years Russian scientists held out hope for conducting another Venus mission—a Soviet specialty during the 1970s—with NASA. But NASA never made this a priority and is now pursuing its own Venus missions. The bigger project was a joint effort with the European Space Agency called ExoMars, which would have landed a European rover on the Red Planet using a Russian lander and rocket. The Russian invasion of Ukraine killed that cooperative effort. Talk about cooperation with China in space has not yielded anything other than more talk. Thus, the future of Russian space science is now mostly dependent upon Luna-25.

But Luna-25’s recent history has not been inspiring.

From July-September 2020, NPO Lavochkin, which was building the spacecraft, conducted thermal vacuum tests of the thermal model spacecraft. By September 2020, the mission was scheduled for launch in October 2021. That launch date was not realistic given the amount of testing that remained to be done, and the launch slipped another year.

By June 2022, the Luna-25 mission was scheduled for launch in September. But according to a report, “a Luna-25 speed and distance sensor required for a safe and soft landing underperformed during testing, leading to the slip from this September into 2023.” The sensor was made by the Vega Concern, a member of Rostec’s Ruselectronics holding company, owned by the Rostech State Corporation.

After testing the device and analyzing the received data, engineers decided that an improvement of the software and the landing algorithms was necessary. By December 2022, the device had passed testing and was delivered to Lavochkin, where it was installed on the spacecraft.

There is even Luna-25 merchandise. If the mission fails, it will probably go on sale. (credit: Lavochkin) |

Over the past decade other countries new to planetary exploration have developed their technical experience and built upon it. China and India flew increasingly sophisticated lunar missions before accomplishing successful Mars missions on their first try. The UAE flew an impressive mission to Mars that benefitted from substantial American assistance. But the Russians only have three decades of planetary mission failures to build on. China currently has more landers planned, for 2025 and 2026, and one of them is supposed to go to the Moon’s south pole. NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program is behind schedule and is a higher-risk effort that could result in failure, but NASA’s track record with planetary spacecraft is not in question.

If Luna-25 succeeds, its data could be of great value to the scientific community. But given the odds, this mission is likely to meet the same fate as Phobos-Grunt 12 years ago.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.