Outgrowing smallsatsby Jeff Foust

|

| “I likened it to the Burning Man of space conferences,” Isakowitz said of the Smallsat conference. |

“It was just a very small room. There were about 50 people in that room,” recalled Sir Martin Sweeting, founder of Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd., of that first conference in a talk last month at the AIAA ASCEND conference. “It was considered somewhat of a hippie convention.”

But as interest grew in smallsats, so did the Small Satellite Conference, to the point where the conference attained almost legendary status in the space industry: a large yet informal gather to exchange technical information and do business, often during breaks that served the university’s Aggie Ice Cream, with flavors like “Aggie Space Debris.”

“For years, I’ve been hearing about the Smallsat Conference,” said Steve Isakowitz, CEO of The Aerospace Corporation, in a keynote at this year’s conference August 5. “I likened it to the Burning Man of space conferences.” (Fortunately, the conference has less dust, and more clothes, than Burning Man.)

This year, the biggest news to come out of Smallsat, as the conference is known, was about the conference itself. After nearly 40 years in Logan, conference organizers announced that next year’s event would move to Salt Lake City.

The move is linked to the growth of the conference itself. What could be contained in a single room or lecture hall soon expanded to take over much of campus: this year, conference sessions were held in an athletic center, while the student union and fieldhouse hosted exhibits, with side meetings in other buildings across campus.

More importantly, booking a hotel room in Logan, a city of about 55,000 a 90-minute drive from Salt Lake City, required either making reservations a year in advance or paying exorbitant rates. Attendees swapped stories of seeing room rates at hotels of more than $500, and even more than $700, per night; a week earlier or later, the same hotels might be charging just $100 a night. Some attendees were commuting an hour each way based on hotel availability.

The move to Salt Lake City and its downtown convention center, with thousands of hotel rooms within a few blocks, was the only way to accommodate the conference’s growth. “It is obvious that to continue to support this rapidly growing industry in the best way possible, Smallsat needs a location with a larger infrastructure,” conference chairman Pat Patterson said in a talk announcing the move.

The Smallsat conference outgrowing its small-town confines parallels the growth of the smallsat industry itself. Interest in smallsats for any range of applications remains strong. But the satellites themselves are growing as demands for greater performance along with emerging launch options encourage developers to make the spacecraft bigger.

Bigger satellites, shrinking numbers

There is no canonical, widely accepted definition for a smallsat. Different companies and organizations set different criteria, usually based on mass, for what is considered small, while others take a Potter Stewart approach: they know a smallsat when they see one.

| “There will always be room for small satellites and miniaturization, but large satellites, in many use cases, are necessary,” Deville said. |

Novaspace, the European consultancy formed earlier this year by the merger of Euroconsult with SpaceTec Partners, classifies satellites weighing no more than 500 kilograms as small. Their latest forecast, continuing those previously done by Euroconsult, found that the number of smallsats to be launched in the next decade is trending down.

The forecast, presented by Novaspace senior consultant Gabriel Deville during a side meeting at Smallsat, projected 14,500 small satellites—by the company’s definition—would launch over the next decade. While a large number, it is significantly less than the 23,000 that Euroconsult forecasted a year earlier.

“It’s because, in the meantime, one operator that launched a lot of smallsats is no longer launching any more: Starlink,” Deville said.

Starlink, of course, is still launching satellites, but they are no longer considered small. While earlier generations of the satellites weighed in at 250 to 300 kilograms, the “v2 mini” satellites SpaceX is now launching weigh an estimated 750 kilograms. The full-sized v2 satellites, optimized for Starship, will be even larger. SpaceX, in effect, graduated from smallsats to bigger ones.

The trend of increasing smallsat mass is not limited to SpaceX. Deville noted that, in 2017, the average mass of smallsats launched that year was 17 kilograms; a time, he said, when “the cubesat was king.” By 2023, that average mass grew to 199 kilograms, influenced by the large number of earlier-generation Starlink satellites SpaceX was launching. But even if broadband satellites like Starlink are removed, the average smallsat mass still grew to 44 kilograms, more than double the average mass from 2017.

That growth, he said, is evidence that smallsat developers are making their satellites bigger for increased capabilities, from service life to payload performance. “A lot of satellites in constellations are seeking more performance, whether it’s in Earth observation or in broadband and connectivity,” he said, with a “sweet spot” emerging around 200 kilograms.

Instead of smallsats killing off larger satellites, as some predicted, smallsats are becoming bigger. “There will always be room for small satellites and miniaturization, but large satellites, in many use cases, are necessary.”

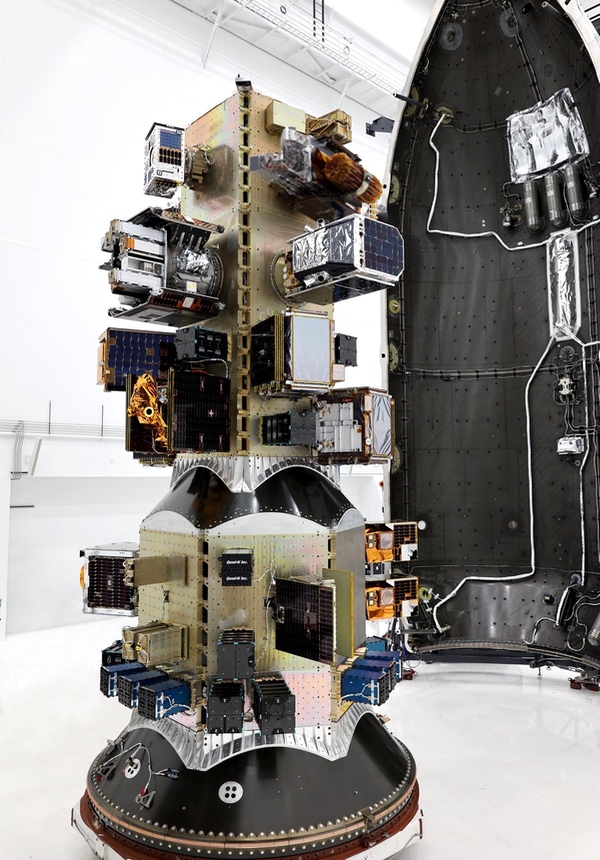

The Transporter-11 mission included 116 payloads, from cubesats to much larger microsatellites. (credit: SpaceX) |

Small rockets versus cake toppers

Several years ago, there was a wave of startups developing small rockets to serve the burgeoning smallsat market, offering dedicated launches for microsatellites down to even cubesats. That field has suffered its share of well-known problems, including technical setbacks: in the last month alone, ABL Space Systems and Rocket Factory Augsburg lost launch vehicles during or after static-fire tests.

Developers of what are often called “microlaunchers” have increasingly looked to move to larger rockets to better serve a market where satellites are getting heavier and where the economics are more promising. Relativity Space dropped its Terran 1 after a single test flight that failed to reach orbit, focusing its resources on the larger, reusable Terran R. Firefly Aerospace has found a market niche with its Alpha small launch vehicle but is working with Northrop Grumman on the larger MLV. Even Rocket Lab, whose Electron is the dominant small launcher in the Western world, is rapidly developing Neutron, a medium-class rocket intended to compete head-to-head with Falcon 9.

Early this year, Rocket Lab forecasted performing 22 Electron launches (of which two would be of a suborbital version of Electron, called HASTE, for hypersonics testing.) An Electron launch earlier this month for radar imaging company Capella Space was the tenth Electron of the year, putting the company well off the pace for 22. Executive acknowledged in an August 8 earnings call that they would likely end up with 15 to 18 Electron launches this year.

They put the blame for that on the customers. “There hasn't been a mission on that manifest that we couldn't support from a production perspective,” said Rocket Lab CFO Adam Spice. “Any volatility we've seen versus that manifest has all been customer delay related.”

Customers, though, have not had any problems showing up for SpaceX rideshare launches. The latest of those, Transporter-11, took place on Friday from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, sending 116 payloads from dozens of customers to Sun-synchronous orbit. Those customers ranged from companies seeking to expand their constellation to startups launching their first satellites, and even space agencies like NASA and ESA.

SpaceX continues to see strong demand for both the Transporter rideshare missions and the new Bandwagon missions to mid-inclination orbits. With Transporter-11, the company has launched more than 1,000 satellites on those dedicated rideshare missions as well as other launches that accommodated secondary payloads.

| “Everybody else has moved on and we haven’t,” Orbex CEO Chambers said of sticking to his company’s microlauncher design. |

SpaceX has worked to standardize as much of the payload accommodation process with a range of options, including the “full plate XL volume” that offers 300 kilograms. But customers wanted more. “We started having more and more customers outgrowing this XL-sized port and asking for more space,” said Jarrod McLachlan, director of commercial sales at SpaceX, during a side session at Smallsat.

The company is now offering larger payload accommodations on those rideshare missions, which it calls “cake toppers” for their location on top of the payload adapter stack, like the ornament on top of a layer cake. “This is really our standard for larger payloads,” he said, supporting satellites weighing 500 to 2,500 kilograms. (That can also support several smaller payloads that need additional volume, which he said are dubbed “cupcake toppers.”)

SpaceX has already flown three rideshare missions with cake toppers, with more to come, he said. The company had not yet standardized the process, and pricing, for those payloads unlike what it does with smaller satellites. “They tend to be more expensive and a little bit more bespoke,” McLachlan said.

Not everyone is moving up in mass to support heaver payloads. Orbex, the UK-based launch company, is pushing towards a 2025 first launch of its Prime rocket, which can place 180 kilograms into orbit. It hopes to target smallsats looking to go to orbits not offered by SpaceX rideshare missions or similar opportunities.

“Everybody else has moved on and we haven’t,” Phil Chambers, CEO of Orbex, said in an interview in July, noting the migration by launch providers to heavier vehicles. “That’s a deliberate decision because then we have a niche for certain missions, payloads that were right-sized for that.”

Even he acknowledged, though, the need to move to larger payloads, suggesting the company would pursue a “block 2” version of Prime with increased performance thanks to improved propulsion efficiencies, as well as potentially a larger vehicle down the road.

Think small

Smallsats remain as popular as ever, even as the spacecraft get heavier. That trend is likely to continue as new launch options emerge like Starship that promise much greater mass and volume for lower prices.

“Big is the new small,” Isakowitz declared in his keynote at the conference, citing those potential new launch capabilities. He suggested that the smallsat philosophy, one of rapid, iterative development and experimentation at low cost, might transfer to bigger satellites.

“If you suddenly find yourself where cost of getting into space isn't a cost to be concerned about and you have no considerations on volume, maybe there's a next generation of satellites that are going to have the same kind of mindset as you all have with smallsats, of cheap and inexpensive, commercial off-the-shelf capability, high production rates, but it just happens to be big: 1,000, 2,000, 3,000 kilograms,” he said.

Maintaining that smallsat ethos as the satellites themselves will be a challenge, just as the Smallsat conference organizers are negotiating that transition as they move from Logan to Salt Lake City, maintaining the collegial environment of the university as they move into literally palatial surroundings: the convention center in Salt Lake City is called the Salt Palace.

“Logan is not what makes this week special,” Patterson said in his announcement of the conference move. “You and your passion for our industry are what makes this week special.” Some things won’t change, though: conference organizers said there will be Aggie Ice Cream next year.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.