Mystery solved! The CALSAT satelliteby Dwayne A. Day

|

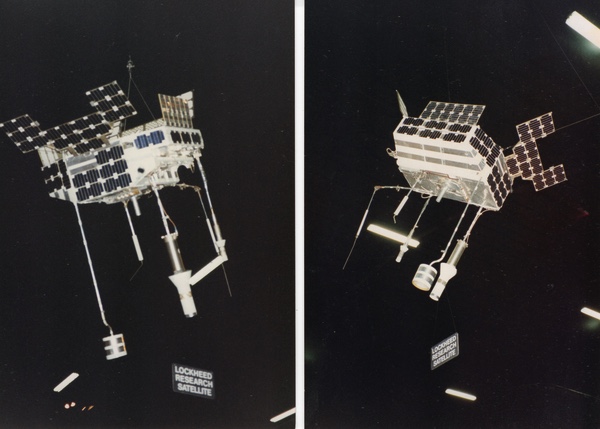

| Sometime later the satellite was hung from the ceiling in one of the museum galleries with the label “Lockheed Research Satellite” and no other information. |

Some information about the P-11s was publicly acknowledged during the 1960s. Artwork of one of the satellites was featured on the cover of a space magazine. Their manufacturer, Lockheed Missiles and Space Company, sought to sell the satellite bus to other government users such as NASA to host payloads. But no civilian or commercial versions were launched during the decade and the satellites remained mysterious.

In June 1970, Lockheed exhibited an actual flight vehicle at an event at Goddard Space Flight Center, outside of Washington, DC, and then turned it over to the Air Force Museum. Sometime later the satellite was hung from the ceiling in one of the museum galleries with the label “Lockheed Research Satellite” and no other information. This author photographed it there during the 1990s. And then at some point, probably after 2010 when the museum underwent a significant expansion, the satellite was removed. Even after the addition of an enlarged space gallery in the late 2010s, it was not re-displayed. Inquiries to the museum on its whereabouts went unanswered.

Information on what the satellite is came to light in the past month with newly declassified documents on American signals intelligence satellites of the 1960s to 1990s. The satellite was one of several that were built but not flown, some of them cannibalized for spare parts; so-called “hangar queens.”

The list of unflown satellites includes over a dozen vehicles, most of them originally classified, a few unclassified and built for the Air Force for research purposes. The names of signals intelligence programs were often idiosyncratic and eclectic, and there were stories behind most of the names, many of which have been lost to time. Sometimes they were inside jokes or references to persons who worked on the programs. By the 1970s, the satellites were named after famous actresses, such as URSALA (apparently misspelled), RAQUEL, and FARRAH.

| The last one—and apparently the only P-11 satellite to be preserved—was CALSAT, for “Calibration Satellite.” It was equipped with a flashing light and beacons to be tracked by ground sites. |

The other satellites built but not flown included NEW HAMPSHIRE, DIPPER, and HAMPER, designed to detect radar signals. DONKEY was built as a P-11 satellite, but its payload for mapping ground signals was removed and attached to another, bigger, satellite named MULTIGROUP 2 (see “The Wizard War in Orbit, Part 3 – SIGINT satellites go to war,” The Space Review, July 5, 2016.) ARYJAN was designed to detect anti-ballistic missile (ABM) radar signals, but apparently canceled when the signals were detected by other satellites. VAMPAN II was also built to detect ABM signals, was dropped from the schedule, and the satellite bus was converted to another mission and flown. EDISON was built to detect signals as a follow-on to another satellite, but was not approved. SEICHE was intended to search for signals in Communist China, but was replaced by a different system. At least one other satellite was built, but, unusually, all information about it was deleted from a list of unflown satellites. Another satellite proposal, SHARON, for Signal Handling And RecognitiON, was apparently never built.

Two other proposed but unbuilt satellites were named GULLY and VALLEY. Like another satellite named ARROYO that was built, they had missions to map out microwave emitter networks, apparently to support a new high-altitude communications intelligence satellite system named CANYON (note the similarity in the names). In an early demonstration of the complementary nature of different satellite systems, higher-resolution reconnaissance satellites soon visually mapped where the microwave transmitters pointed, and there was no need to do this by mapping the signals.

The CALSAT satellite hanging in the National Museum of the United States Air Force during the 1990s. Identified only as “Lockheed Research Satellite,” there was no signage explaining the satellite‘s mission. It was later removed from display and is probably in storage in a museum facility. It may be the only remaining satellite of the P-11 type in existence. (credit: photos by author) |

There were two or three P-11s that were built for unclassified Air Force missions. ASTEC I and II were built to “measure long term space effects on reflectivity of various mirror surfaces.” (Another document spells them as “AZTEC.”) ASTEC I was bumped off several launch vehicles in favor of higher-priority ABM missions, and eventually returned to the manufacturer for spare parts. It is unclear if ASTEC II was ever built. The lack of suitable rides into space was a frequent problem for the users of the P-11 satellites.

The last one—and apparently the only P-11 satellite to be preserved—was CALSAT, for “Calibration Satellite.” It was equipped with a flashing light and beacons to be tracked by ground sites. It was designed to be used for calibrating satellite tracking ranges. One document indicates that like AZTEC, it was also returned to the manufacturer for spare parts. But another document states that CALSAT was “taken out of storage in June 1970 for display by LMSC at a space conference at Goddard and later delivered to the Air Force Museum.”

Now that the mystery of the satellite’s identity and purpose have been discovered, there is one remaining big mystery: what happened to CALSAT? Perhaps it is sitting in a crate in a giant warehouse in Dayton, Ohio, next to the Ark of the Covenant. Hopefully, it will again see the light of day.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.