Boldly going: Star Trek and spaceflightby Dwayne A. Day

|

| It should be no surprise that Gene Roddenberry, Star Trek’s legendary creator, borrowed language from a White House publication. Various accounts of the creation of Star Trek have discussed its ties to the then-thriving Southern California aerospace community. |

The document was originally written by Dwight D. Eisenhower’s newly-created Presidential Science Advisory Committee, or PSAC, in early 1958. The chairman of PSAC, James Killian—a legendary scientific and intelligence advisor in Washington politics—created “Introduction to Outer Space” as a document explaining spaceflight “for the nontechnical reader,” meaning the President of the United States. Eisenhower directed that it be publicly released as a brochure. In his preface, Eisenhower explained “this is not science fiction. This is a sober, realistic presentation prepared by leading scientists. I have found this statement so informative and interesting that I wish to share it with all the people of America, and indeed with all the people of the earth. I hope that it can be widely disseminated by all news media for it clarifies many aspects of space and space technology in a way which can be helpful to all people as the United States proceeds with its peaceful program in space science and exploration… These opportunities reinforce my conviction that we and other nations have a great responsibility to promote the peaceful use of space and to utilize the new knowledge obtainable from space science and technology for the benefit of all mankind.”

Many thousands of copies of “Introduction to Outer Space” were printed and distributed, and they can occasionally be found at used book sales, buried with old pamphlets and folded National Geographic maps. It is not a rare document from the early space age.

Star Trek is easily the most analyzed science fiction television show ever produced. Surprisingly, whereas many of the original shows fans considered it to be groundbreaking and espousing liberal values—it featured a multiracial cast and the first interracial kiss, for instance—many of those who have written about the show from a scholarly perspective consider it to be not any of these things. They label the original series as “reactionary nostalgia” and claim that it reinforced the status quo, not to mention stereotypes. Of course, this is undoubtedly a reflection of the field of film and television theory, which was long dominated by different “schools” that are intent upon critiquing American culture—the Marxist school, the feminist school, etc. Besides a political bias by the writers, it may also reflect an inability to view the subject material in the context of its era: what seemed rather bold and original in the latter 1960s—an integrated crew, Russians and Americans (and a Scotsman) working alongside each other—looks relatively unremarkable nearly three decades later. However, there was also a certain amount of validity to these critiques, for the original series did feature a ship commanded by an American captain and crewed by mostly white men, and the occasional woman in a miniskirt. Star Trek was not the avant garde of American culture in the late 1960s. Even Gene Roddenberry admitted in a 1968 interview that there were limits on how far he could go: “Today in TV you can’t write about Vietnam, politics, labor management, the rocket race, the drug problem realistically.” Trek used metaphor.

Writing in the latest issue of the Journal of Cold War Studies, Nicholas Evan Sarantakes argues that Star Trek’s creators “wanted the United States to play a constructive role on the world scene” and claims that “they used the television show to critique U.S. foreign policy.” Sarantakes claims to be one of the few scholars to actually study the original source material for the show, such as production memos and notes, as opposed to simply watching old episodes.

| The transition from aerospace company to Star Trek was more direct—someone at Douglas Aircraft gave one or more models of this proposed space station to Gene Roddenberry, who then gave them to Richard Datin, a model-builder who modified them and turned them into the K-7. |

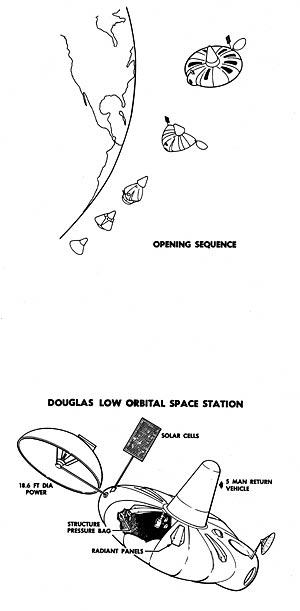

But no matter what the argument about the politics of Trek, it is clear that the show had links to the Cold War aerospace industry, in many different ways. Several years ago book dealer Glen Swanson (www.liftoffbooks.com) came across a copy of a 1960 proposal from Douglas Aircraft for an extendable space station, apparently for launch atop a Saturn rocket. The space station has an odd shape, a donut with a conical reentry vehicle at the center. The donut folded out like opening a handheld fan, and the reentry vehicle would fit at its center. Swanson theorized that this shape was later adopted for the famous “The Trouble with Tribbles” episode, where it formed the basis of the “Space Station K-7,” which was overrun by furry little rodents with a fondness for eating and reproducing.

An illustration of a space station concept by Douglas Aircraft that may have been the inspiration for the K-7 space station on Star Trek. (credit: Douglas Aircraft) |

According to Mike Okuda, who served as the graphics designer for several of the Star Trek movies in the 1990s and on the later television shows, the transition from aerospace company to Star Trek was more direct—someone at Douglas Aircraft gave one or more models of this proposed space station to Gene Roddenberry, who then gave them to Richard Datin, a model-builder who modified them and turned them into the K-7. A colleague of mine who used to work in the Southern California aerospace industry says that he suspects that the models were more likely fished out of a dumpster by an enterprising collector, something that he and his buddies used to regularly do in search of office supplies as well as more valuable discoveries.

Perhaps now, with the study of popular culture, and Star Trek, gaining a little more respectability (as evidenced by it being a topic in a Cold War studies journal), an enterprising scholar can do a little academic dumpster diving, chronicling the links between Star Trek and the space race. Not exactly a bold voyage, but one that might contain a few surprises along the way.