COTS: what does the customer want?by Jeff Foust

|

| CSI’s solution to the last mile problem takes advantage of “proven in orbit” technology, namely, the Progress spacecraft and its docking system. |

Throughout this time CSI has been coy about what technical solution it was proposing to deliver cargo to the ISS. The “LEO Express” system, according to the company’s web site, would utilize standardized cargo containers—analogous to the shipping containers used in terrestrial intermodal transportation—and technologies that are “‘off-the-shelf’ and proven in orbit”, but beyond that CSI kept the technical details of their approach confidential.

However, in a presentation during the NewSpace 2006 conference July 21 in Las Vegas, CSI CEO Charles Miller provided the most detailed public explanation to date of CSI’s ISS cargo concept. The CSI concept, he explained, is designed to deal with the biggest problem with ISS operations: spacecraft rendezvous and docking, also known as the “last mile problem”, an issue that has delayed the development of cargo vehicles like Europe’s ATV and Japan’s HTV. “This is the key business problem that CSI set out to solve,” he said.

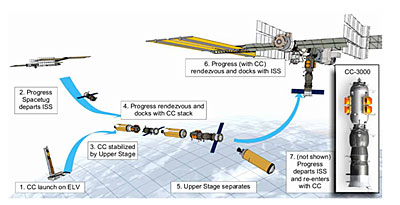

CSI’s solution to the last mile problem takes advantage of “proven in orbit” technology, namely, the Progress spacecraft and its docking system. A cargo canister—a module derived from the cargo compartment of a Progress spacecraft with docking ports at both ends—is launched into low Earth orbit on a rocket such at the Atlas 5. Rather than go directly to the ISS, however, the cargo module stays a safe distance away from the station. A Progress spacecraft already at the ISS then undocks and maneuvers to the cargo canister, docking with it. The Progress/cargo module stack would then redock with the ISS, using the same docking ports and Kurs radar system as an ordinary Progress spacecraft.

An illustration of how CSI’s LEO Express system would work. (credit: CSI) |

This approach is scalable, according to Miller: the cargo canister can be stretched to accommodate varying amount of internal and external cargo. The module could be launched on a wide range of US and foreign launchers, depending on the amount of cargo being sent to ISS, since all the launcher needed to do was place the canister in the vicinity of the station. The major components of the canister itself have decades of flight heritage from the Soyuz and Progress spacecraft, as well as derivatives like the Shuttle-Mir docking module and the Pirs docking/airlock module on the ISS; only the Progress avionics required a minor revision. “Every piece is TRL 9, proven on orbit,” said Miller, using the NASA technology readiness level designation for flight-proven hardware.

| “What happened in the last few months was that the COTS program basically evolved away from being about ISS cargo delivery,” said Miller, “and has turned into a US industrial development program, and has put more focus on crew than cargo.” |

CSI brought in a number of other companies for its COTS proposal, most notably RSC Energia, which would build the cargo canisters and handle the Progress “spacetug” operations. Lockheed Martin would provide launch services for the cargo canister; Miller added that Lockheed was also interested in investigating an “all-US cargo path” for the LEO Express system. Other partners provided everything from cargo handling expertise to insurance and a line of credit. CSI also received a patent (“Method and apparatus for supplying orbital space platforms using payload canisters via intermediate orbital rendezvous and docking”) for its overall concept.

With this combination of proven technology and industry partners, it would seem that CSI would be a leading contender for a COTS award. Yet, when NASA selected a half-dozen companies as finalists for the program in May, CSI was not on the list. Instead, NASA selected Andrews Space, Rocketplane Kistler, SpaceDev, SPACEHAB, SpaceX, and t/Space for further consideration. What happened to CSI?

Miller said that an unnamed “senior COTS program manager” told the company in a June debrief that CSI had “a very good ISS cargo proposal”. The problem, Miller was told, was that “this wasn’t really what this was about.” In other words, the goals of the overall COTS program had apparently changed, and to CSI’s disadvantage.

“What happened in the last few months was that the COTS program basically evolved away from being about ISS cargo delivery,” said Miller, “and has turned into a US industrial development program, and has put more focus on crew than cargo.”

While CSI’s reliance on RSC Energia appeared to hurt the company in the COTS proposal, Miller defended the decision to work with the Russian manufacturer. “We basically adopted best commercial practices,” he said. “We outsourced to get the best value.” Such practices are hardly unprecedented in aerospace and other industries, Miller pointed out: Boeing uses Russian engineers to help design commercial airliners, and there is widespread use of Russian and Ukrainian hardware in the commercial launch industry, such as the Atlas 5’s RD-180 engine.

Is Miller’s assessment of COTS correct? From a technical standpoint it’s difficult to say: most of the six finalists have released few, if any, specifics about their proposals. Two of the six finalists, Rocketplane Kistler (RpK) and SpaceDev, presented at the NewSpace 2006 conference in a session immediately preceding Miller’s talk, but offered few details about their COTS proposals that they have not previously disclosed. Other companies, like Andrews Space, have said even less, making a comparison of the technical merits of the various proposals all but impossible.

On the business side all six finalists represent relatively small companies: the two largest, SpaceDev and SPACEHAB, have a couple hundred employees each and, while publicly traded, have market caps only in the low tens of millions of dollars. While larger established aerospace companies are playing a role in the COTS program—just last week Orbital Sciences and RpK announced a “strategic partnership” in support of RpK’s COTS bid—that role is a supporting, not a leading, one.

Even before the COTS program was formally unveiled last year, NASA was talking about ways to build up the aerospace industrial base in the country by harnessing the power of competition. In a speech before the Space Transportation Association in June 2005, NASA administrator Michael Griffin spoke glowingly of the hypercompetitive atmosphere of Silicon Valley, then said, “I think we can all admit that that type of competition is largely lacking from today’s aerospace business. It’s out there but it is not the industrial base which uses up most of the DOD space dollars or the NASA space dollars.” His challenge, he said, “is how do we engage that engine of competition more productively, so that it can work on behalf of space business?”

Engaging that “engine of competition”, though, doesn’t mean putting all of the agency’s eggs in it. Griffin made it clear in the same speech that “there must be a government-derived capability to service the space station, even after the shuttle is retired,” something agency officials have reiterated on many occasions since then. That capability will take the form of the Block 1 version of the Crew Exploration Vehicle (CEV), a contract for which NASA may announce shortly after making the COTS awards—despite a recent GAO report that concluded that the agency had not done enough work to properly define the overall effort.

There is also the issue of the budget for COTS. NASA is planning to spend no more than $500 million on the COTS demonstration program through 2009, assuming Congress approves the planned spending levels for the program in the 2007 budget (currently being hashed out on Capitol Hill) and beyond. While NASA expects companies to line up substantial private funding to supplement its contribution, there is the question of whether that $500 million is sufficient to fully develop a commercial ISS resupply system, given that the money will probably be split among two or more companies. Conventional wisdom in the industry has NASA making two awards, although an executive with one of the finalists believes that NASA could end up making three awards, apportioning the bulk of the money to two companies while giving a small study contract to a third company to keep them alive and ready to step in should one of the other two stumble.

| CSI is philosophical about their loss in the COTS competition. “We don’t get upset at NASA,” Miller said. “They weren’t buying what we were offering.” |

Last week, the Space Frontier Foundation issued a white paper arguing that NASA needed to spend much more than $500 million on COTS. It advocates funding a “much larger and aggressive COTS program” by skipping ahead directly to the Block 2, or lunar, CEV, freeing up “many billions of dollars” that could be used in part to support COTS by making more and larger awards. Eliminating the Block 1 CEV would also, the Foundation argued, remove a government-funded competitor to commercial ISS resupply options.

While it seems unlikely that NASA would willingly adopt this approach, it does raise a number of questions about both COTS and the overall exploration program. If COTS is primarily more about supporting the US space industry than developing commercial ISS resupply alternatives, what are its metrics for success? Is the funding proposed for COTS sufficient to achieve those goals? How much more money—if any—is needed to also ensure, or at least improve the odds of, the development of a commercial resupply option? Can such a system be developed at the same time NASA is building what may be perceived as a competing system with the Block 1 CEV? Congress may tackle questions like those this fall in hearings expected on the CEV program.

In the meantime, CSI is philosophical about their loss in the COTS competition. “We don’t get upset at NASA,” Miller said. “They weren’t buying what we were offering.” He remains optimistic, though, that NASA will look their way again in the near future for ISS cargo resupply options, regardless of what happens with COTS. “They changed their mind once, we believe they’ll change it again.”