The making of an Enterprise: How NASA, the Smithsonian and the aerospace industry helped create Star Trekby Glen E. Swanson

|

| Gene Roddenberry actively sought out and used scientifically literate people and agencies not only to show technical realism in his series but also to help guide the show’s popular fiction. NASA, the Smithsonian, and the aerospace industry worked to help ensure that the series would have a three-season run that allowed it to take on new life through syndication. |

At this time NASA, the Smithsonian, and the larger aerospace community of the 1960s helped provide technical advice, influence, and support to Gene Roddenberry during the creation of his original Star Trek television series. Science fiction writers and fans rallied in support of the show through letter-writing campaigns and public demonstrations designed to help convince network executives to keep the show. At the same time, elements within the aerospace industry, including important figures at NASA and the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum, also helped save the series by working behind the scenes to convey a level of credibility, respect, and approval along with a certain cachet that, together, helped influence network executives to fund production of the show for three full seasons before the series ended in 1969. With 79 episodes completed, the studio could now recoup their investment by offering networks a syndicated package that allowed them to show Star Trek in multiple outlets every day of the week all over the world.

How did American culture, as well as NASA and the aerospace industry, influence Star Trek? Gene Roddenberry actively sought out and used scientifically literate people and agencies not only to show technical realism in his series but also to help guide the show’s popular fiction. NASA, the Smithsonian, and the aerospace industry worked to help ensure that the series would have a three-season run that allowed it to take on new life through syndication, thereby creating legions of new Star Trek fans that would support its growth and popularity to make it the phenomenal enterprise that it is today.

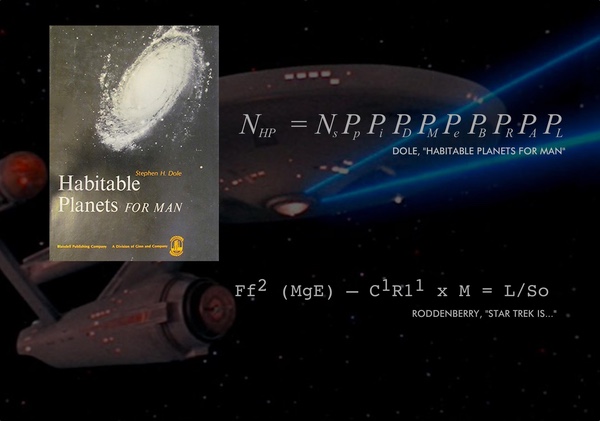

Roddenberry was not above twisting science to suit his needs. Here he made use of an official RAND report to fabricate an equation that looked good to NBC executives to help sell the series but was completely and utterly false. (credit: RAND/CBS/Paramount) |

Star Trek’s producer and driving force was Gene Roddenberry. A former B-17 pilot during World War II and commercial pilot for Pan Am, as well as a police officer, his aviation experience enabled him to speak effectively to members of the aerospace industry, many of whom were former pilots and veterans themselves.

Roddenberry stayed in touch with other pilots that he met after the war. Don Prickett was one of those people who served with Roddenberry during World War II, and he was Roddenberry’s closest friend.

When Roddenberry first began to develop Star Trek, Prickett put him in touch with Harvey Lynn, a physicist who worked for the RAND Corporation. After the war, individuals within the War Department and the Office of Scientific Research and Development began to look at how they could form a private organization that would connect the military with research and development. Out of this effort came Project RAND—“Research ANd Development.”

Roddenberry was impressed with Lynn when they first met during the summer of 1964 at his RAND office in Santa Monica, California. “On the basis of meeting with a number of personnel there, [Lynn] seems the best qualified to serve as technical consultant and/or coordinator of technical advice once Star Trek is rolling,” wrote Roddenberry. “He also has access to government and industry libraries, film footage and even some miniaturized models of planet exploration ships and machines.”[1]

Lynn was hired by Roddenberry and worked part-time as a consultant for the series during its first season while still working for RAND. Among Lynn’s contributions to Star Trek were the terms “phaser” and “tractor beam.”

| When Roddenberry began developing Star Trek, 15 of the 25 largest aerospace companies were located in the greater Los Angeles area. Many were situated close to Paramount’s Desilu Studios where the series was made. |

Roddenberry not only made use of one of RAND’s physicists, he also incorporated some of their published reports. In 1962, RAND scientist Stephen Dole prepared a study for the United States Air Force that involved estimating the probabilities of finding habitable planets in the galaxy. When his report came out in book form two years later under the title Habitable Planets for Man, Roddenberry took notice. Jeffrey Hunter, the actor who played Captain Christopher Pike in Star Trek’s first pilot, “The Cage,” references this report in an early 1965 interview: “The thing that intrigues me the most about the show is that it is actually based on the Rand Corp projection of things to come.”[2]

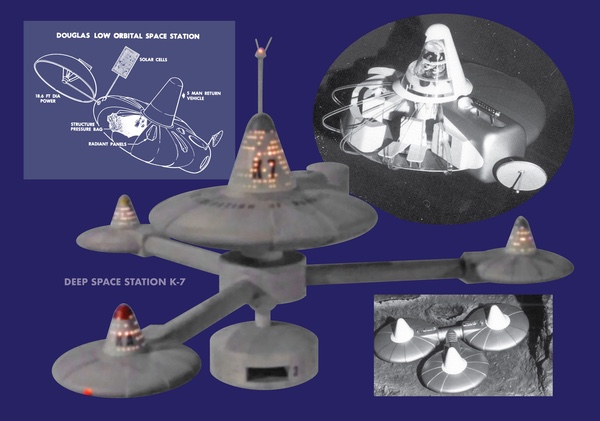

The model of the K-7 space station as seen in the Star Trek episode “The Trouble with Tribbles” is based upon an actual design that was first proposed in a 1959 study by aerospace engineers at Douglas Aerospace. The model miniature used in the series was made from study models obtained by Roddenberry from the company. (credit: G. Swanson/CBS/Paramount) |

At the end of WWII, 60–70% of the American aerospace industry was based in Southern California. The good climate and open land that helped draw aviation to the region also helped lure the motion picture industry. When Roddenberry began developing Star Trek, 15 of the 25 largest aerospace companies were located in the greater Los Angeles area. Many were situated close to Paramount’s Desilu Studios where the series was made.

Roddenberry drew upon the most current spaceflight technology then available to incorporate into Star Trek. He read, wrote, phoned and even dumpster-dived to get material for his new series.

A direct example of how the aerospace industry influenced Star Trek appears in the episode “The Trouble With Tribbles.” In this episode furry little creatures that “coo” and have a tremendous desire for eating and breeding overrun the Federation’s K-7 space station.

The principal elements of the K-7 as it is shown in the episode first appeared in a report done by Douglas Aircraft. The 1959 study outlined the operational requirements of an extendable orbiting space station. Constructed on Earth then launched atop a “Saturn-type missile,” the station was designed to automatically unfold in space into a donut-shape with a conical reentry vehicle at its center.[3]

Richard Datin, a model maker who helped build the original production model Enterprise, described how the K-7 design materialized. “I was told upon viewing the original model, and maybe by Roddenberry, that he obtained it [the Douglas space station model] from Douglas Aircraft whose main office was in nearby Santa Monica. Apparently, Gene had a following from people in the space industry, particularly Caltech in Pasadena.”[4]

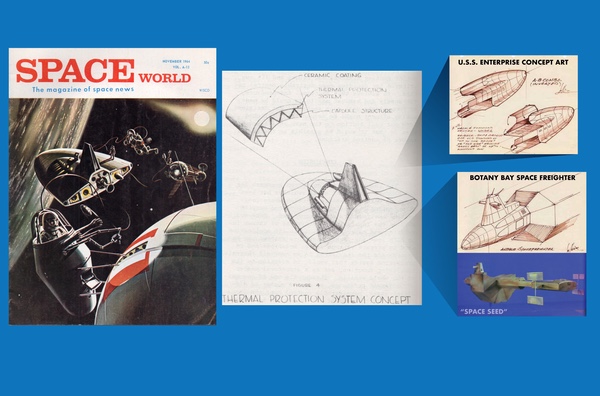

The design of Khan’s ship the Botany Bay from the classic episode “Space Seed” may have been inspired by a 1960 symposium sponsored by NASA and RAND. (credit: Palmer Publications/NASA/CBS/Paramount) |

How Roddenberry first became aware of the Douglas design, either by seeing an actual model or the report about it, is not clear. A year later, the original 1959 Douglas study was included in published proceedings from a manned space station symposium that was co-sponsored by NASA and RAND. Appearing in these proceedings, alongside illustrations of the Douglas space station model that inspired the K-7, was another drawing that may have also caught Roddenberry’s eye.

In the 1960 symposium proceedings, there appears a paper that focuses on the thermal control of spacecraft and includes an illustration showing a thermal protection system for a proposed spacecraft.[5] In comparing this illustration to several made by Matt Jefferies, the artist responsible for designing the Enterprise, there is an uncanny resemblance to the sleeper ship S.S. Botany Bay as seen in the episode “Space Seed.” Jefferies, like Roddenberry, had been a pilot during World War II, still loved to fly, and was very familiar with technical issues. Studying the various conceptual sketches created by Jefferies used to help define the finished design that appears in the series, one can see a submarine-like form begin to emerge. One drawing made by Jefferies illustrating an early configuration for the Enterprise is remarkable in its similarity. The spacecraft exterior grid pattern seen in the drawings combined with the angled vertical dorsal tower causes one to wonder if Jefferies may indeed have been influenced by the symposium proceedings.

Other aerospace companies also shared their support for the series. Representatives from General Electric’s Aerospace Division and Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory toured the Star Trek sets and conducted interviews with cast members in 1968.[6] They also volunteered to help with the production, perhaps out of respect that a showrunner for a new science fiction television series would take an interest in their technical support.

| Roddenberry knew that to sell a serious television show based upon science fiction, he had to break the mold that resulted in previous mediocre efforts. |

The military also took an interest in the new series. On May 5, 1967, the Air Force’s elite Aerospace Research Pilot School, used by NASA to help train its astronauts, invited Roddenberry and the show’s cast to visit their facilities and attend graduation exercises at Edwards Air Force Base.[7,8]

Air Force lieutenant colonel Dr. Jack LeRoy Hartley was so taken by Star Trek after watching the first episode that he sent off the following telegraph to Gene Roddenberry the next day: “TREMENDOUS THOUGHT PROVOKING EXCELLENT CAST AND SCENERY SUSPENSEFUL OUTSTANDING PLEASE ACCEPT CONGRATULATION AND PLEA TO CONTINUE.”[9]

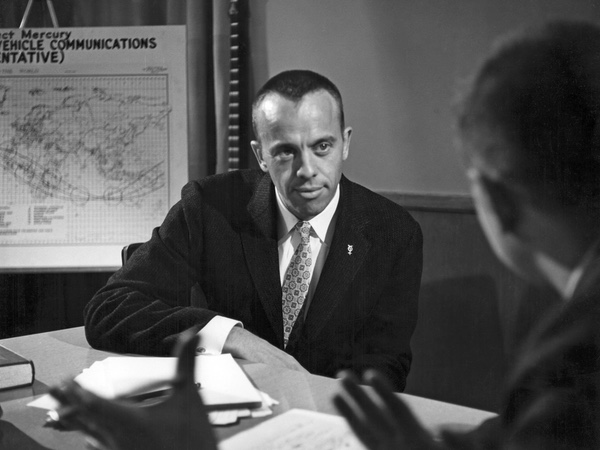

Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Dr. Jack LeRoy Hartley, father of astrostomatalogy, is shown with the portable dental kit that he developed for NASA’s early astronauts. Hartley’s work may have influenced the design of Dr. McCoy’s medical bag and other surgical instruments shown in the series. (credit: UPI/CBS/Paramount) |

Hartley served at Brooks Air Force Base where he studied the problem of what to do if an astronaut got a toothache while in space. Faced with the time-consuming problem of halting a simulated space flight in a vacuum chamber because an astronaut had a bad tooth, Hartley began to think about what would happen if the victim had the same problem in outer space.

As a result, Hartley developed the science of astrostomatology along with a portable dental kit for the Aerospace Medical Division of the Air Force Systems Command. The compact kit, weighing just a few pounds and containing 26 instruments, was specifically designed for use by NASA’s astronauts and was the result of two years of work at the Air Force’s School of Aerospace Medicine at Brooks Air Force Base.

In addition to the congratulatory telegraph that he sent to Roddenberry, Hartley may have also offered the kit to Star Trek. After all, Dr. Leonard “Bones” McCoy, the ship’s doctor, uses a portable medical kit in the series. Star Trek fans sometimes saw the good doctor carrying a small-bagged kit along with a small pouch that contained a hypo-spray, the 23rd century’s equivalent of today’s syringe.

When asked Hartley’s daughter, Patricia, about her father’s role in Star Trek, she replied, “he collaborated a fair amount with Roddenberry. He [Roddenberry] was really very good about trying to get things right, in spite of the fact that he had a very limited budget. And he didn't have a lot of tools to show. But he created a whole lot of things. And Dad was just one of the ones that he was talking to help him design this stuff.”[10]

Hartley received attention for his work as a result of several published papers and newspaper articles. He also promoted astrostomatology and his astronaut dental kit through appearances on such television shows as To Tell the Truth and What’s My Line. Today, Hartley’s original kit resides in the collections at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

| NASA asked Kelley to “tour facilities and watch experiments and tests” reasoning that, “this would be good for Star Trek and helpful in his portraying of the Chief Surgeon of the U.S.S. Enterprise.” |

During the series’ original run, 16mm prints of Star Trek were made available to the military. Consolidated Film Industries (CFI) of Hollywood was contacted by the Bureau of Naval Personnel to obtain permission to manufacture prints of Star Trek to be used for “direct projection solely for Navy personnel aboard ship.”[11] This was a service done by CFI for the military at minimum cost and as a cooperative effort for the Navy morale program. As described in a letter from CFI to Roddenberry, “To-day (sic) we received a call from Washington, requesting us to contact you for permission to manufacture prints of your series Star Trek.”[12] The letter went on to explain that these prints would not be used for “any land-based stations or through TV facilities which might interfere with your syndicated program.”[13] After being used for a period of two years, the prints would be destroyed with an affidavit indicating that effect given to the studio by the Department of the Navy.

Roddenberry knew that to sell a serious television show based upon science fiction, he had to break the mold that resulted in previous mediocre efforts. He emphasized very early on the “science” part of “science fiction” as he sought to help embed a level of believability and technical accuracy into Star Trek. The support that he received early on during the initial development of the series from the aerospace community was encouraging and he continued to actively solicit their help during the production run of the entire series.

05 The Federation meets NASA. Cast members from Star Trek are shown meeting test pilots at NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center. Shown at left is James Doohan, who played Chief Engineer Montgomery Scott or “Scotty,” talking with NASA pilot Bruce Peterson. Behind them is the Northrop M2-F2, one of several experimental wingless research aircraft developed for NASA. DeForest Kelley, who played Dr. McCoy in the series, is shown talking with Bill Dana (middle photo) and inspecting the X-15-1 (Vehicle No. 56-6670) with Gene Roddenberry, Joe Pevney, Bob Justman and Matt Jefferies (back to camera). (credit: NASA) |

Star Trek was the most-watched program during its 8:30pm time period that Thursday evening when the first episode aired on September 8, 1966. As mixed reviews came out the next morning, NASA was preparing to launch Gemini 11. Roddenberry knew that critics of the show could not discount the fact that those that watched fictional characters travel through space from their televisions would be the same audience that watched real astronauts do the same thing from Cape Kennedy. For them, NASA made space flight real and Star Trek offered a similar view that was impossible to miss. As a result, Roddenberry made every effort to reach out to NASA for support with his new series and they were more than happy to oblige.

In an article that appeared in the December 1967 issue of Popular Science, Star Trek is described as “the only science-fiction series in history that has the cooperation and advice of the National Astronautics and Space Administration.”[14]

Throughout Star Trek’s production, Roddenberry sought to actively engage the actors who played characters from a space-age 23rd century by having them take part in space-related events of the 20th century. NASA sent them invitations to attend various conferences and events held by the space agency.

On March 31, 1967, DeForest Kelley, who played Dr. McCoy, the ship’s doctor, was invited by NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston to be the guest of Dr. Charles Berry, the chief surgeon for all the astronauts. NASA asked Kelley to “tour facilities and watch experiments and tests” reasoning that, “this would be good for Star Trek and helpful in his portraying of the Chief Surgeon of the U.S.S. Enterprise.”[15]

NASA employed the good doctor of the Enterprise to give comfort to the Apollo 7 crew during their mission in space. Shortly after launch in October 1968, the crew developed head colds and McCoy tried to provide some relief. During their ten-day mission, he sent them the following telegram: “I do not make house calls but under the circumstances would be pleased to beam aboard and take care of the common cold. (signed) Bones.”[16]

Kelley, along with Gene Roddenberry and actor James “Jimmy” Montgomery Doohan, who played the series’ chief engineer Montgomery Scott or “Scotty,” were invited to tour NASA’s Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Joining them for the tour on April 13, 1967, was Walter Matthew “Matt” Jefferies, Jr., art director and production designer for the series; Herbert Schlosser, who at that time, was head of NBC’s programming that oversaw Star Trek’s development during the network’s production of the series; assistant director, production manager and associate producer Gregg Peters; series director Marc Daniels; assistant director and producer Robert “Bob” Harris Justman; and director Joseph “Joe” Pevney. Both Daniels and Pevney would go on to eventually direct nearly half of all the original Star Trek episodes.

These folks were creating spacecraft from the future while studying the latest high-performance aircraft from the present. “Scotty” met with NASA test pilot Bruce Peterson while the press took photos of the two standing in front of Northrop’s M2-F2, an experimental wingless research aircraft. A month after their meeting, Peterson was flying the M2-F2 on a test flight when he lost control shortly before landing. The vehicle crashed, somersaulting across a dry lakebed before finally coming to a stop. Amazingly, Peterson survived and the footage of the crash was used at the beginning of every episode of the popular 1970s TV series The Six Million Dollar Man.

As they continued their tour, DeForest Kelley spoke with Bill Dana, a NASA X-15 pilot, while looking at one of the three X-15s built by North American Aviation for NASA. This particular X-15-1 (Vehicle No. 56-6670) was piloted by Neil Armstrong, who would later travel to the Moon during Apollo 11 in another North American-built spacecraft. Star Trek’s cast, creator and producers together fawned over a real spaceship, one that had flown to the final frontier and back just two years earlier by Joe Engle who flew it to a maximum altitude of 50.47 miles (81.2 kilometers), just above the recognized boundary where space begins.

Alan Shepard, the first American to travel into space during his historic May 5, 1961, suborbital flight and the fifth man to walk on the Moon, was asked to appear in Star Trek. (credit: NASA) |

There was even an effort to try and get astronaut Alan Shepard to appear on the show.[17] Shepard, the first American to travel into space during his historic May 5, 1961, suborbital flight and the fifth man to walk on the Moon during Apollo 14, was asked to play a minor role in the series. Shepard could not accept payment for the part but agreed to have Roddenberry film a one-minute spot for his favorite charity in exchange for the appearance. Sadly, the deal never materialized. However, the studio tried again, this time inviting astronaut Scott Carpenter, who also declined.[18] Both Shepard and Carpenter eventually did make it to the franchise, though many years later. Shepard appears in the opening credits to the spinoff series Enterprise that ran from 2001 to 2005 showing him being suited up for his Apollo 14 lunar mission. Scott Carpenter’s voice can be heard in the teaser trailer for J.J. Abrams’ 2009 Star Trek that includes his famous words “Godspeed, John Glenn.”

In a 1966 memo, Roddenberry wrote how Edward A. Orzechowski, a public information specialist at NASA’s Western Operations Office in Santa Monica, “was very interested in Star Trek and most anxious to provide us with all sorts of help including stock footage, valuable models, animation, technical advice, even access to some NASA labs and proving ground.”[19]

| Shepard, the first American to travel into space and the fifth man to walk on the Moon during Apollo 14, was asked to play a minor role in the series. Sadly, the deal never materialized. |

Evidence of NASA’s contributions in the series is present from the very beginning. In the first pilot “The Cage,” during the sequence when the Talosians are going through the Enterprise’s computer records, multiple images flash across one of the bridge view screens. It turns out that many of these images were taken from original NASA documents that were seen and approved by Roddenberry. In a memo dated November 23, 1964, when “The Cage” was in postproduction, Roddenberry sought images to show in the scene where the Talosians are “extracting” information from the U.S.S. Enterprise.[20] In a follow-up memo issued to Darrell Anderson, one of the optical houses that filmed the special visual effects, Roddenberry gives a detailed annotated list of NASA documents, pamphlets, and papers complete with instructions on what pages to be filmed for the “Subliminal, Knowledge Montage” sequence.[21] Of the 19 confirmed NASA images that appear in this “slide show” nearly half of them come from SPACE The New Frontier, a publication produced by NASA. (See “‘Space, the final frontier’: Star Trek and the national space rhetoric of Eisenhower, Kennedy, and NASA”, The Space Review, April 20, 2020.)

Star Trek made use of NASA imagery. Still photos from the Gemini program appeared in the episode “Court Martial” and footage of various Saturn V launch vehicles were shown in the episode “Assignment Earth.” (credit: CBS/Paramount/NASA) |

In “Court Martial,” a first season episode of Star Trek, there are scenes from an office on a Federation Starbase where viewers can clearly see NASA photos from the Gemini Program hanging on the walls. The season two episode “Assignment Earth” incorporates extensive use of NASA stock footage from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center showing the Saturn V launch vehicle. Ground and aerial footage are mixed throughout the episode, which includes scenes of both the Saturn V (SA-500F) Facilities Integration Vehicle as well as Apollo 4 (SA-501) that was first launched on November 9, 1967. The episode “The Cloud Miners” also used a photo of Earth taken from the Gemini 4 mission (see “From Project Gemini to the final frontier”, The Space Review, March 23, 2009.)

The influence that America’s space program had on Star Trek goes beyond simply providing interesting photos and footage. Every episode of the series opens with the instantly recognizable monologue: “Space, the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise. Her five-year mission: to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before.” There is evidence that Kirk’s iconic opening line may have been attributed to the US government.

In 1958, the same year that NASA was formed, the Senate formed a Special Committee on Space Technology in response to the previous year’s launch of Sputnik to help clarify the nation’s goals in space in light of the perceived Soviet threat. They issued a report titled “Recommendations to the NASA Regarding A National Civil Space Program” that outlined the nation’s civil space program’s mission “to explore, study and conquer the newly accessible realm beyond the atmosphere.” This is a similar goal to that of the familiar five-year mission of the Enterprise “to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations.”[22]

An article by spaceflight historian Dwayne Day makes the argument that the last line of the series’ opening narration “to boldly go where no man has gone before” may have been influenced by a document issued by the White House (see “Boldly going: Star Trek and spaceflight,” The Space Review, November 28, 2005).

In response to the launch of Sputnik 1, Dr. James R. Killian, chairman of the Presidential Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) under President Eisenhower, produced Introduction to Outer Space. The 1958 document was designed to help educate the general public about the relatively new concept of spaceflight and to help generate support for the president’s new civil space program. The document noted “…the compelling urge of man to explore and to discover, the thrust of curiosity that leads men to try to go where no one has gone before.”[23] Though not exactly the same as Kirk’s “to boldly go where no man has gone before,” the document was highly readable and, as a result, proved popular. Thousands of copies were produced in pamphlet form and sold through the Government Printing Office. Whether Roddenberry directly borrowed language from any of these sources is not known for certain, but he certainly had access to them.

NASA even arranged to have Roddenberry view a launch from the agency’s Western Test Range at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. The launch was very early in the morning and Roddenberry arrived in his limo to tour the range and view the launch with his oldest daughter Dawn. On the morning of August 16, 1968 at 3:30 am, they witnessed the launch of a Delta rocket. The satellite on board was one in a series of spin-stabilized operational meteorological satellites whose name prior to launch was TIROS Operation System (TOS-E). It was renamed after launch “ESSA-7” derived from that of its oversight agency, the Environmental Science Services Administration (ESSA). These satellites were built by RCA for NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and designed to monitor weather including sending regular television images of the Earth from orbit.[24]

In a letter to James Webb, NASA’s Administrator, Roddenberry expressed his appreciation for all of NASA’s support: “I have never received friendly and efficient cooperation anywhere near that provided by your Agency.”[25]

Even though NASA supported the series, it was reluctant to take any credit since government agencies frowned upon being seen participating in commercial ventures. Roddenberry made it clear to everyone that NASA does “not wish to be mentioned, and we have assured them we will comply with their wishes.”[26]

| As Nimoy later recalled of his visit to NASA Goddard, “this was the first real taste that I had of the NASA attitude towards Star Trek.” |

Despite NASA’s reluctance to take any credit, it continued to work behind the scenes to help the fledgling new series. One of the biggest contributions the space agency made to the series began with the assistance of Alberta Moran. In 1967, Moran was the assistant to John F. Clark, then director of NASA’s Goddard Spaceflight Center. She was also one of the founders of the National Space Club.

Comprised of industry and government representatives along with educational institutions and the press, the National Space Club sought to promote leadership in the burgeoning new field of astronautics. One way they did that was to sponsor the Goddard Memorial Dinner. Held in Washington, the annual dinner is named after American space pioneer Robert H. Goddard and recognizes persons and institutions that have made outstanding contributions to space science and technology during the previous year. Moran chaired the special events committee that was responsible for assembling the invitation list for the Goddard Dinner.

“We were at my house with Bob Hood, the president of the National Space Club,” recalled Moran. Hood was president of Douglas Aircraft and co-founder of the National Space Club. “We were getting the invitation list together for the Goddard Dinner and my oldest daughter, Penny, came in and said, ‘Why don’t we invite somebody from Star Trek?’”[27]

Moran first tried to invite Gene Roddenberry, Star Trek’s creator, but he couldn’t make it. Neither could William Shatner who played Captain James T. Kirk. Moran told her daughter, “I couldn’t get Captain Kirk, but I got Mr. Spock.”[28]

In some ways, this was a bigger coup. Spock was becoming the breakout character on the show, something that for a while rankled Shatner. Spock was particularly popular among women.

On March 14, 1967, Leonard Nimoy arrives at Dulles International Airport outside of Washington to tour NASA and attend the Goddard Memorial Dinner. Shown picking up Mr. Spock are (left to right) Anne Moruz, Penny Moran, Cheryl Dale, Alberta Moran and Leonard Nimoy (Mr. Spock). (credit: NASA) |

On March 14, the day before the Goddard Dinner, Leonard Nimoy landed at Dulles airport outside of Washington, DC. Joining Moran to meet him was her daughter Penny and two of her daughter’s friends, Anne Moruz and Cheryl Dale, all of whom were avid fans of the series and thrilled over the prospect of finally meeting Mr. Spock in person. After picking up Nimoy from the airport, they drove him to the hotel where he was besieged by fans with questions about the show.

The next morning, Nimoy’s wife Sandy joined him for a tour of NASA’s Goddard Center. Upon arriving, both he and his wife discovered that a major part of the population of the xenter, including secretaries and scientists, were there to greet them at the front door. As Nimoy later recalled of his visit, “this was the first real taste that I had of the NASA attitude towards Star Trek.”[29]

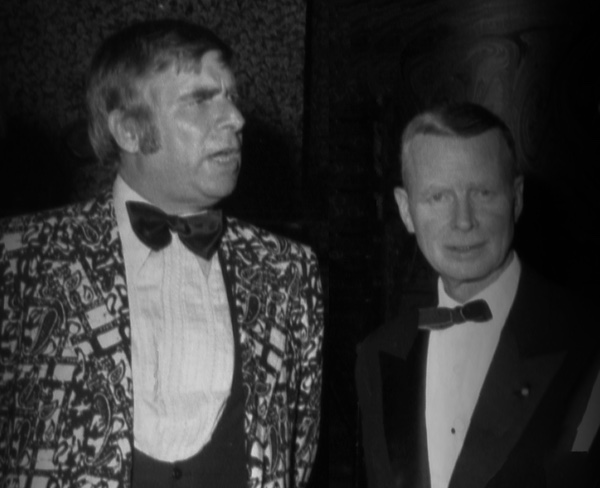

That evening after the tour, Leonard Nimoy attended the Goddard Dinner. All the top space people from NASA and its contractors were at the black-tie affair, including astronaut John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth. Barely six weeks after the Apollo 1 fire that took the lives of astronauts Chaffee, White, and Grissom, the mood among everyone present was tempered by the realization that the Moon landing would be delayed. Some even speculated that the Apollo program might be canceled altogether.

At the reception, Nimoy was introduced to those who would share the front table with him. In addition to astronaut Glenn, those seated at the dais included NASA Administrator James Webb, Robert Goddard’s widow, and Vice President Hubert Humphrey.

(large photo at right) Alberta Moran briefing Leonard Nimoy. Bottom left photo shows Leonard Nimoy and his wife Sandy touring NASA Goddard while listening to Paul Henley, head of the Spacecraft Integration and Rocket Division. Upper left photo is astronaut Colonel John Glenn and his wife Annie talking with NASA administrator James Webb during the Tenth Annual Goddard Dinner held at the Sheraton Park Hotel in Washington, D.C. on March 15, 1967. Photo below right is Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, Chairman of the National Aeronautics and Space Council, talking with Mrs. Robert H. Goddard, and Congressman George P. Miller, U.S. House of Representatives at the Goddard Memorial Dinner. (credit: NASA) |

The memory of the accident was still very much in the minds of everyone that evening. As the vice president launched into his speech, he acknowledged to the more than one thousand attending guests,[30,31] “we cannot help but keep in mind that this is an occasion for remembrance with sorrow, and also with great pride of three gallant men and three of my friends and your friends.”[32]

At the end of the vice president’s speech, people gathered around Nimoy. “They were all most cordial,” wrote Nimoy. “All of them wanted autographs and pictures for themselves and their children.”[33] Moran recalled how Webb, Glenn, and Humphrey were very excited to get Nimoy’s autograph.[34]

Men had been flying into space for less than seven years. Star Trek was showing people exploring the galaxy hundreds of years into the future. However, in the wake of the Apollo 1 tragedy, everyone seemed to pause. Many questioned if going to the Moon was still worth the risk.

| Nimoy wrote of that evening, “I do not overstate the fact when I tell you that the interest in the show is so intense, that it would almost seem they feel we are a dramatization of the future of their space program.” |

But that evening, people looked beyond what had recently happened with the fire. While shaking hands and signing autographs, those attending the dinner saw not just an actor in their midst, but Mr. Spock, a representative from the future who knew that what they were doing in their century may have been painful but was necessary for them to move forward into the next. For the half a million workers employed to support the Apollo program during one of the darkest hours in NASA’s history, Star Trek gave them hope.

Nimoy wrote of that evening, “I do not overstate the fact when I tell you that the interest in the show is so intense, that it would almost seem they feel we are a dramatization of the future of their space program, and they have completely taken us to heart… they are, in fact, proud of the show as though in some way it represents them.”[35]

“I have seldom seen one of our people return from a trip so pleased and so enthusiastic about those he met there,” wrote Roddenberry in a letter to Moran shortly after Nimoy returned from the dinner.[36] That trip proved to be more than a display of support by aerospace engineers and NASA for the new television series. It was an affirmation of Roddenberry’s continual effort to work with them during the series’ production.

In his letter Roddenberry acknowledged that, “we will be more than happy to work more closely with you folks, with NASA and with others in the space industry. You can be certain we will include in upcoming shows some ‘plugs’ about the importance of the funds, the planning and the rest of the ‘pioneer’ effort that made star travel eventually possible. We feel sincerely about this and hope our show helps establish throughout the country the certainty of this future and the necessity of adequately planning for it.”[37]

It was a love affair between NASA and Star Trek.

NASA astronaut Colonel John Glenn (left) and the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum Assistant Director of Astronautics Frederick C. Durant III are pictured on May 2, 1966 examining a model of the proposed new National Air and Space Museum. Durant was close personal friend and a powerful early advocate of Star Trek. (credit: Smithsonian Institution Archives Image#OPA-876R2-C) |

That evening during the March 1967 Goddard Dinner, while NASA officials, congressmen, and the vice president approached Leonard Nimoy for pictures and autographs, another individual stood nearby. Richard Preston, an administrative officer with the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, was waiting his turn to deliver an important message to Nimoy: the Smithsonian wanted a copy of the show’s second pilot episode.

Roddenberry first tried to sell his new series to network executives with the production of an initial pilot called “The Cage.” It failed to impress NBC executives who reportedly called the pilot “too cerebral,” “too intellectual,” and “too slow.” Rather than reject the series outright, the network took the unprecedented step of commissioning a second pilot called “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” which was accepted by NBC allowing the studio to move forward with production of the series.

The fact that no other show in the history of television had ever had a copy of its pilot placed in the Smithsonian was unique. But Preston was just the messenger. Who in the Smithsonian initiated the request?

Frederick C. Durant, III before his death in 2015 at age 98, was fortunate to live long enough to witness not only the birth of the space age but also play an active role in its development.

| Durant’s gift for collecting left the Smithsonian with some of the finest artifacts chronicling the history of spaceflight. It made sense that he would also want to include something that would portray its future. |

After receiving a degree in Chemical Engineering, Durant enlisted in the US Navy. A peptic ulcer prevented him from being deployed overseas during World War II but that did not keep him from serving at home. Trained as a naval aviator, he worked as a flight instructor teaching new cadets how to make carrier landings on a training ship in the Great Lakes.

Upon retiring from the Navy, Durant went on to serve as a consultant and engineer in various research labs including stints with the Department of Defense. His new arena of combat during the Cold War was outer space.

Durant was an ardent promoter of space flight. A space geek, he served in a variety of positions in newly formed organizations that supported the nascent field of astronautics. He was President of the American Rocket Society, now known as the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, and spearheaded the growth of the International Astronautical Federation. He became a fellow of innumerable astronautical societies, many of which he helped form.

He rubbed elbows with noted scientist and author Arthur C. Clarke and helped Wernher von Braun launch Explorer 1, America’s first artificial satellite. In 1964, Durant joined the staff of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum and became Associate Director for Astronautics. An avid science fiction fan that enjoyed collecting space art, Durant eventually struck up a friendship with Roddenberry.

Durant had excellent collecting skills, and he had been around long enough to know lots of people… important people. Aerospace historian Randy Liberman, a close personal friend of Durant’s during his later years, recalls that, “With a telephone call, he could bring together top brass or captains of industry.”[38]

When Durant retired from the museum in 1980, his gift for collecting left the Smithsonian with some of the finest artifacts chronicling the history of spaceflight. It made sense that he would also want to include something that would portray its future.

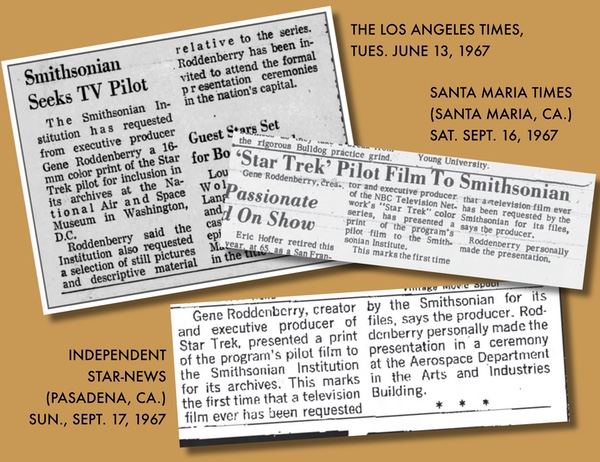

With the encouragement of Fred Durant III, the Smithsonian requested and received a copy of the second Star Trek pilot. This marked the first time that a television pilot was requested by the Smithsonian. (credit: assorted newspapers) |

Richard Preston’s meeting with Nimoy that evening during the Goddard Dinner initiated a series of letters and phone calls between the Smithsonian and producers.[39,40] “We believe the Star Trek pilot would be a valuable addition to the archives of the National Air and Space Museum. Science Fiction forms a definite segment of astronautics chronology,”[41] wrote the Smithsonian in a 1967 letter to Roddenberry explaining why they wanted a copy of it.

On August 28, 1967, against a backdrop of a Command Module from NASA’s Apollo Program, Rodenberry formally presented a 16mm color print copy of Star Trek’s second pilot to S. Paul Johnston (then director of the National Air and Space Museum) during a formal press event held in the Smithsonian’s Arts and Industries building.[42,43,44] This presentation marked the first time that a television film had ever been requested by the Smithsonian for its files. In the eyes of the public and the media, it gave the series a level of credibility and acceptance.[45]

On August 28, 1967 during a formal ceremony held at the Aerospace Department of the Arts and Industries Building, S. Paul Johnston, director of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum is presented with a copy of Star Trek’s pilot by Gene Roddenberry, the series creator and executive producer. (credit: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum Archives) |

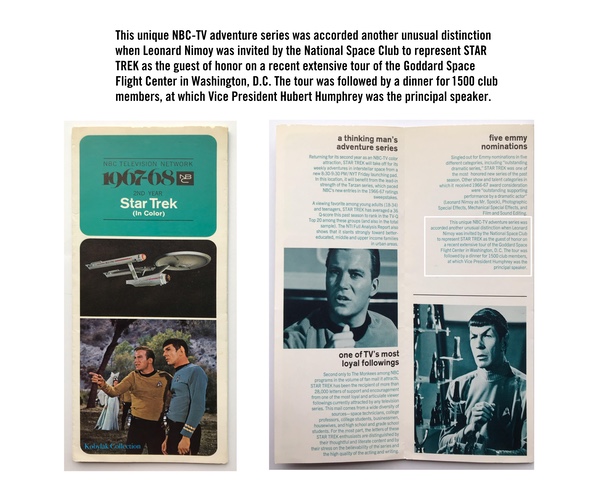

Just a few days before the Goddard Dinner, Roddenberry received word from NBC that Star Trek would be renewed for a second season. Paul L. Klein, Vice President of Audience Measurement for NBC, wrote in the May 27, 1967, issue of TV Guide: “Star Trek is the only science-fiction show on television with a scientific basis. I was instrumental in recommending Star Trek for the NBC schedule and have been one of the show’s staunchest supporters during the agony of renewal time. Messrs. Roddenberry, Coon and the whole Star Trek staff have deserved the public’s approval, NBC’s faith in them, and, as topping to the cake, were just recently honored by the National Space Club in Washington for their scientific validity.”

This was good news in that it increased, but in no way guaranteed, the chances that the series would be renewed for a third season. Star Trek was popular during its first airing, but it was in syndication that the series really took off. In fact, Star Trek would become the most popular syndicated television show in the history of network programming, generating millions of new viewers and fans from around the world.

The honor given by the Smithsonian through its acquisition of the pilot combined with the demonstrated support given by NASA and the larger aerospace community served to strengthen the credibility of Star Trek. Together, they conveyed a level of respect, approval and a certain cachet that not only helped the series survive for three seasons but also to promote the show as seen in this 1967-1968 NBC promotional brochure. (credit: NBC/Bill Kobylak) |

But first it had to survive its third season. In the world of 1960s television, a series needed to stay on the air for a minimum of three years. If not, the studio almost always lost money.

| Some of Star Trek’s most loyal followers were those who worked at NASA and in the aerospace industry. |

When Star Trek first aired, NBC gave it the highly favorable viewing time of Thursday evenings beginning at 8:30 p.m. During the second season, the time stayed the same but the day moved to Fridays, a less favorable slot especially for high school and college students who made up most of the show’s viewing demographic.

As Roddenberry notes in an August 13, 1967, interview, “We were making out fine where we were, but now we may lose many of the young people who’ve been watching, because Friday is the night they like to go out.”[46]

By late 1967, when it looked like the series would not be able to secure a third season, fans came to the rescue by engaging in a massive letter-writing campaign that generated a lot of attention.

“Star Trek is the ‘in’ show with the people who work at NASA, Caltech and the space plants,” said Roddenberry during an interview that year. Boasting that NBC received an average of over 4,500 letters per week Roddenberry went on to say that, “we get letters from curators of museums and college presidents, all of whom appreciate our serious attempt to portray what space travel will be like.”[47]

Some of Star Trek’s most loyal followers were those who worked at NASA and in the aerospace industry. In reflecting upon the influence that NASA had on the series, Leonard Nimoy recalled, “We were kind of the NASA connection; the NASA fantasy and the show that NASA watched” and that association gave it “a new kind of respectability… and a certain kind of credibility.”[48]

On March 1, 1968 at 9:28 pm, following the first-run airing of the Star Trek episode “The Omega Glory,” an NBC announcer came on the air telling viewers that the series would continue to be seen on television that fall.

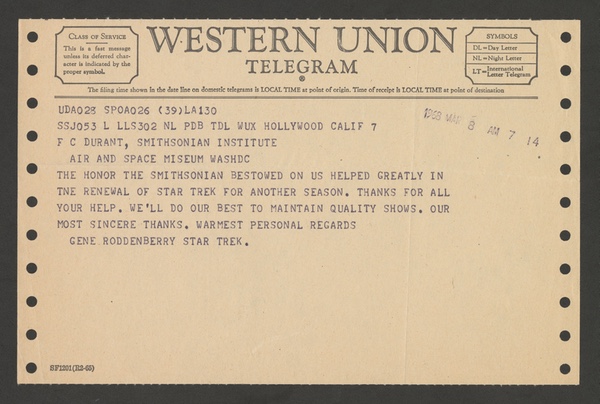

Seven days after NBC announced Star Trek’s renewal, one of the first things that Roddenberry did was send Fred Durant the following telegram: “THE HONOR THE SMITHSONIAN BESTOWED ON US HELPED GREATLY IN THE RENEWAL OF Star Trek FOR ANOTHER SEASON. THANKS FOR ALL YOUR HELP. WE’LL DO OUR BEST TO MAINTAIN QUALITY SHOWS. OUR MOST SINCERE THANKS. WARMEST PERSONAL REGARDS.”[49]

Shortly after learning of NBC’s decision to grant the series a third season, Gene Roddenberry sent this telegram to Fred Durant III on March 8, 1968. Durant’s efforts helped influenced NBC into deciding to renew the series for a third season which helped Star Trek to take on new life through syndication. (credit: Smithsonian Institution Archives) |

Even though Roddenberry won the battle Star Trek lost the war.

For its third season, Star Trek would end up still airing on Friday nights but at an even later starting time. Friday evenings were date nights for the 14-21-year old age group that made up the majority of Star Trek’s viewers. The show had already begun to lose its audience when the series switched to 8:30–9:30 pm Friday evenings for the second season. Now the show would be on even later from 10:00–11:00 pm. Rodenberry as well as every television producer knew this was the “death slot.” The third season would be Star Trek’s last.

During the tumultuous decade that Star Trek premiered, Rodenberry recalled, “we were just getting into space. When we made our first episode, we hadn’t even been to the Moon. Then Star Trek came along and said, ‘Hey, we made it!’ It’s a program that said there is basic intelligence and goodness and decency in the human animal that will triumph over these things.”[50,51]

| Fifty-five years after its premiere, Gene Roddenberry’s original vision is still very much relevant. |

The honor given by the Smithsonian through its acquisition of the television film combined with the demonstrated support given to the series by NASA and the larger aerospace community served to strengthen the credibility of Star Trek. Together, they conveyed a level of respect, approval, and a certain cachet that helped the show survive its original three-year run on NBC. While fans almost unanimously agree that the show’s last year was its worst in terms of quality, those final 24 episodes are what allowed Star Trek to take on a new life through syndication creating legions of new fans that would promote its growth and popularity for decades to come.

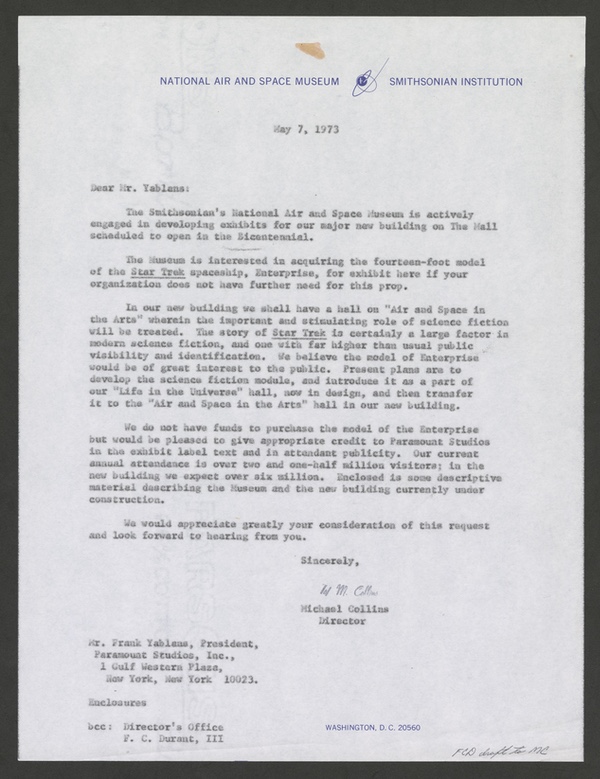

Apollo 11 astronaut and National Air and Space Museum Director Michael Collins wrote Paramount on May 7, 1973 asking if they would donate the original production model Enterprise to the Smithsonian. Note the hand written “FCD draft to MC” at the bottom right of the letter. “FCD” is Frederick C. Durant III who drafted this letter. (credit: Smithsonian Institution Archives) |

In the fall of 1974, the Smithsonian opened a new exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum. The “Life in the Universe” exhibit premiered in the Arts and Industries Building before taking up residence in the new museum that was being built on the National Mall. Prominently featured in the exhibit was the original 11-foot production model U.S.S. Enterprise used in the filming of the series.

After securing the Star Trek pilot for the Smithsonian, Durant led the museum’s effort to obtain the U.S.S. Enterprise. In explaining the reasons why the Smithsonian wanted the model, Durant described, “Our interest in acquiring Star Trek memorabilia relates to the study of the influence of science fiction upon future technological development. We believe that consideration of science fiction is relevant to current and future accomplishments in space.”[52]

When the new National Air and Space Museum opened during America’s bicentennial in 1976, the world’s most famous starship and one of television’s most iconic cultural artifacts became a permanent exhibit in the Museum’s Milestones of Flight Hall near its Independence Avenue entrance.

“We believe that science fiction can play a ‘mind-stretching’ rule in the minds of creative, scientific and technically inclined persons,” wrote Durant when asked about the Smithsonian’s interest in Star Trek. “All three of the acknowledged rocket pioneers, Tsiolokovsky, Goddard and Oberth, acknowledged the influence of Jules Verne. In addition, Goddard had high interest in H.G. Wells’ First Men on the Moon. The large number of scientific and technical professionals who indulge in speculative fiction today reinforces this view… Star Trek represents the same kind of invitation to imaginative thinking.”[53]

On September 19, 1974, the Smithsonian held a special gala dinner in conjunction with the opening of their new “Life in the Universe” exhibit in the Smithsonian’s Arts and Industries Building that first housed the Air and Space Museum. The exhibit featured the 11-foot full-sized production model U.S.S. Enterprise used in the filming of the original television series that Paramount donated. The exhibit along with the Enterprise model moved to the museum’s new building on the National Mall when it opened in 1976 where it was the centerpiece of the new “Life in the Universe” Gallery. Pictured here attending the 1974 dinner gala is Star Trek’s creator Gene Roddenberry (left) with Fred Durant III. (credit: Smithsonian Institution Archives Image). |

Gene Roddenberry died on October 24, 1991. On January 30, 1993, his widow, Majel, accepted NASA’s Distinguished Public Service Medal on behalf of her husband from the space agency’s administrator, Dan Goldin, during a ceremony held at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. The citation accompanying NASA’s highest award read: “For distinguished service to the Nation and the human race in presenting the exploration of space as an exciting frontier and a hope for the future.”

Fifty-five years after its premiere, Gene Roddenberry’s original vision is still very much relevant. No longer owned by NBC, the franchise continues to thrive as the series has taken on new life through a network of online streaming services. Today, with multiple new television series in production as well as talk of more cinematic versions, Star Trek continues to transcend generations, mediums and even science itself thanks to the initial help and support given by NASA, the Smithsonian and those within the aerospace community that believed in it.

The original 11-foot production model U.S.S. Enterprise became part of the Smithsonian’s permanent collections in 1974. It remains one of the most popular artifacts displayed on the main floor of the National Air and Space Museum where it is viewed by millions of visitors every year. (credit: Karl Tate/CBS/Paramount) |

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.