The last flight of Helo 66by Dwayne A. Day

|

| Countless photographs and television pictures show the white helicopter with a big “66” painted on its side hovering over Apollo astronauts newly returned from the Moon. |

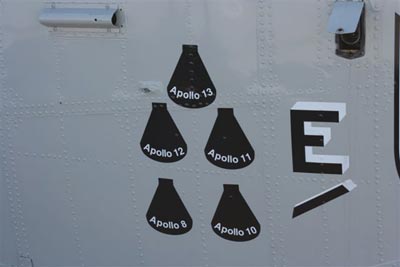

In San Diego, California sits a well-preserved aircraft carrier named the USS Midway. The Midway served in the US Navy from 1945 until 1992. It was mothballed and then turned into a museum ship open to the public in 2004. On the Midway’s deck sits a white Sea King helicopter painted with the famous 66 squadron number. Painted on the nose of the helicopter are the silhouettes of five Apollo capsules. But walk around to the other side of the helicopter and you’ll see the number “68” painted on the other side. So, is this the famous Apollo-era Helo 66 or not?

If you head about 800 kilometers to the northwest, to Pier Three at the former Alameda Naval Air Station and go aboard the USS Hornet Museum, on her aft flight deck you will see another Sea King, also painted with a large “66” on the side of her fuselage.

Unfortunately, neither aircraft is the real helicopter. The real Helo 66, the one in all of those famous Apollo era photographs, was lost at sea off the coast of San Diego in 1975. That helicopter, BuNo 152711, crashed during training for hunting Soviet submarines.

Starting in late 1968, the “Black Knights” of Navy Helicopter Anti-Submarine Squadron Four (HS-4) began training for recovering Apollo spacecraft. Over the next couple of years HS-4 was involved in the recovery efforts for Apollo missions 8, 10, 11, 12, and 13, flying off the USS Hornet, among other ships. It is the silhouettes of those capsules that are painted on both replicas on the Midway and the Hornet. The members of HS-4 received the Navy’s Meritorious Unit Commendation ribbon for their Apollo role.

Above: another replica of “Helo 66”, this one on the deck of the USS Midway in San Diego. Below: a closeup of the helicopter shows the icons representing the five Apollo recoveries performed by the real helicopter. (credit: D. Day)  |

But Helo 66 did not always fly with that number. After it had already made several Apollo recoveries, the Navy switched to a three number squadron designator and so helicopter number 66 became number 740. But before each recovery effort the squadron repainted “66” on the side of the aircraft. After Apollo 13 the Navy began using other aircraft for the Apollo recoveries. Helo 66, or by now number 740, was still a relatively new and frontline aircraft, and so it returned to performing HS-4’s primary mission of hunting submarines.

In the summer of 1975 Lieutenant Leo S. Rolek, copilot Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Charles D. Neville, and two crewmen took off in the early evening from the Naval Auxiliary Air Field at Imperial Beach, California. They were on an anti-submarine sonar training flight and Rolek flew the helicopter out to a designated training area off the coast from San Diego. They began operations, which involved making approaches to a specified location and dipping their sonar into the water. The Sea King’s sonar lowered through a large hole in the helicopter’s fuselage and when it entered the water it opened up like the spokes of an umbrella and extended its sensors.

The crew reported in to base every half hour that everything was going fine until about 9:30. The helicopter lowered its sonar to about 30 meters below the water’s surface when the aircraft became unstable, apparently because of the sonar being dragged in the water and pulling the helicopter. The sonar operator lowered the sonar deeper, hoping that this would improve stability. But something happened. Something bad. And one of the dangerous aspects about helicopters is that bad goes to worse very quickly.

| Helo 66 remains at sea, and her legacy lives on in the movies and the photographs and the museums. |

According to reports, the helicopter was “pulled” into the ocean. It impacted the water, broke up, and began to sink. Just how it broke up is unclear—helicopters are at the mercy of their spinning rotor blades, and if a blade impacts the surface it can spin the fuselage around and slam it into the water or at the very least create massive pieces of high velocity debris. Because the heaviest part of a helicopter is the engines mounted over the cabin, most helicopters immediately tip over when they hit the water and crews are trained to exit a sinking upside down helicopter. The amazing thing is that all four men managed to escape the helicopter. They were picked up by a Coast Guard HH-3F helicopter just before midnight and were taken to the Naval Hospital in San Diego. Sadly, pilot Leo Rolek suffered a ruptured spleen and died of his injuries three weeks later.

Exactly how the accident happened remains unclear from the heavily censored official accident report which was released several years ago. Unfortunately, overly zealous Navy censors deleted substantial parts of the report, making it difficult to determine what happened and why—all it says is that “aircraft impacted water in rearward flight from hover at 40 feet.” The censors even deleted the names of the four men aboard the helicopter, despite the fact that they have been known for decades. But according to a former Sea King pilot, it was notoriously easy to accidentally back the Sea King into the water while in a hover, especially at night. Although the Sea King’s boat-like fuselage and outriggers for its landing gear implied that it could float, the reality was that the heavy engines and rotors would cause it to tip upon settling onto the water unless the rotors continued to provide lift. But even worse was that the dipping sonar required cutting a large hole in the center of the fuselage. If a Sea King touched down on the water, even gently, it could immediately flood, becoming too heavy to get airborne.

Several years ago a group of helicopter and space enthusiasts heard rumors that Helo 66 had been found in much shallower water than the Navy had originally reported. Supposedly divers had found the fuselage in relatively good shape and for a brief period of time the enthusiasts sought to form a recovery effort to bring the famous Sea King to the surface and restore her. But the effort foundered when they were eventually told that the reports had to be in error, because the helicopter broke up when it hit the water and could not have been intact.

So Helo 66 remains at sea, and her legacy lives on in the movies and the photographs and the museums.

Apollo 8

Recovered 27 December 1968

Pilot: Commander Donald S. Jones

USS Yorktown, CVS-10

Apollo 10

Recovered 29 May 1969

Pilot: Commander Chuck B. Smiley

USS Princeton, LPH-5

Apollo 11

Recovered 24 July 1969

Pilot: Commander Donald S. Jones

USS Hornet, CVS-12

Apollo 12

Recovered 24 November 1969

Pilot: Commander Warren E. Aut

USS Hornet, CVS-12

Apollo 13

Recovered 17 April 1970

Pilot: Commander Chuck B. Smiley

USS Iwo Jima, LPH-2